Our final group analysis was guided by the following objectives:

- Identifying the key problems and social norms within the communities we visited

- Prioritize and group the problems

- Look at existing resources within the communities

- Identify activities we can modify in our existing work plan

- Based on the research define what empowerment of females within these communities will look like

- Action Plan: where do these finding fit? How can we include them into our work plan? How can we make them happen?

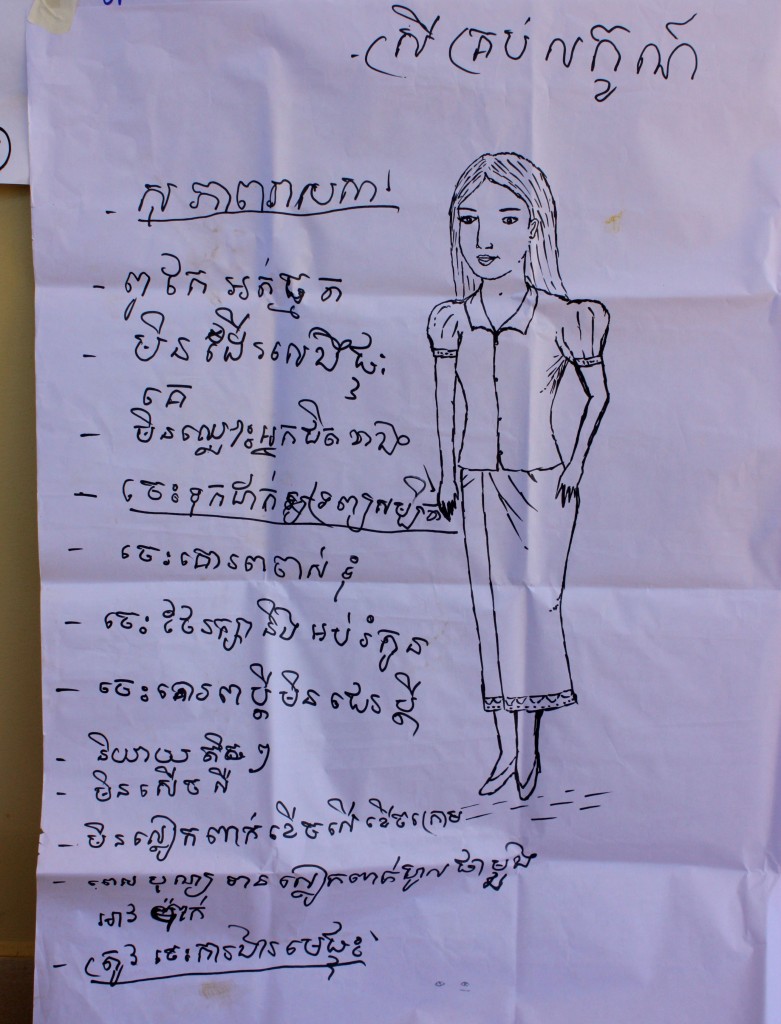

First we wrote down the problems and Social norms which stood out to us in both field visits. We then posted all of those findings on the board, and together categorized them into clusters. We ended up with four main categories:

- Household Equity

- Social Norms

- Livelihoods

- Nutrition

In groups we identified the main issues in each category and the role cultural beliefs, social norms and practical matters (such as access to resources) play. Combining these findings with the suggestion we had received from the respondents, we set about finding activities that could be incorporated into the Fish on Farms strategy.

I will use my group’s findings to demonstrate what the process involved and what the conclusions looked like. Please keep in mind that the following solutions are from our initial impressions only and do not represent the final results.

In my group we focused on Household Equity and identified three areas that needed improvement:

i- Reducing the burden of household chores on women

ii- Reduce alcohol consumption of men

iii- Involve women in household decision making

We proposed the following as means of achieving these goals

i- Reducing the burden of household chores on women

Involve men in the training and education sessions so they are more aware of what the household chores involve. In the training sessions take a proactive approach; for example have the men prepare a meal. This way the men can experience what the process involves.

ii- Reduce alcohol consumption

Using role play, involve the men in the discussion about alcohol consumption and try to obtaining their opinion and identify circumstances that lead to drinking. For instance what are the social pressures that lead to drinking? Concurrently we can put a strong emphasis on the potential of the money that is spent on alcohol; we will add up the amount spent on alcohol within one year and talk about what they could use that money for ( ie. Farming equipment).

iii- Involve women in household decision making

In our research we found that women can make small daily decisions such purchasing household ingredients. However, when it comes to making bigger decisions such as selling household assets they do not have authority. We attributed this to two factors: 1- A lack of income from women, 2- Lack of confidence in decision making.

To empower the women we hope to generate income through the Fish on Farms project. We will complement this by training the women in book keeping and budgeting. To enhance the women’s confidence levels we concluded that it is important to recognize their achievements and reward good decisions.

While coming up with these solutions our goal was to involve all members of the household, since it is the household as a unit which can drive the change and not individual members.

The next step of the baseline gender analysis is to start coding all of the summaries from our interviews on the field, and this will involve nothing more than an able body (ie. me), a laptop, and a long list of summaries to review. So stay tuned for the next post which will explain what coding is and what the process involves.