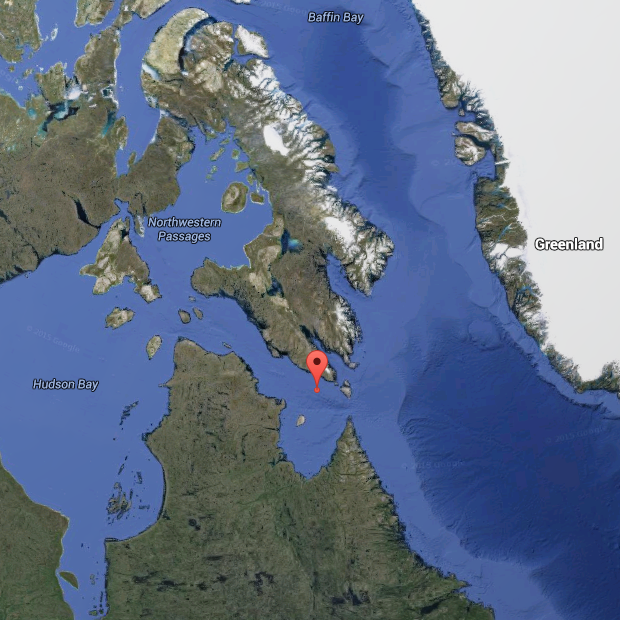

As we wait in the Hudson Bay (update here) before we head north again, we bring you this blog’s first Expedition Science Special! Part of the excitement of being on a research expedition is that there is a large group of scientists from around the world working together, and we get to hear about the work they do. On the blog, I’ll be conducting interviews with some of the scientists on board to hear about their research here in the Arctic. (The recordings are shipboard-quality, and sometimes you can hear the ship creaking in the background…) For our first instalment of the E.S.S., I interviewed Dr. Jay Cullen about his group’s trace metal work. You can listen to the podcast right here! (Transcript below.)

Dr. Cullen fixing a trace metal rosette.

Interview Transcript:

One of the exciting things about the Amundsen expedition is that it brings together scientists from around Canada and the world to do research together. On the blog, we’re going to be interviewing some of them to hear them talk about their work here on the Amundsen. Today we’re going to be speaking to Dr. Jay Cullen. Jay is a professor at the University of Victoria, where he heads the Cullen Lab, which does research on trace metals in the ocean.

So Jay, broadly, could you tell us what the focus of your research is?

The focus of my research is to understand how the chemical forms that metal elements take in seawater affect their behaviour. For example, metals that are important nutrients for microbes that grow in the ocean, like iron or copper, and the chemical form that they take determines whether or not they’re accessible to the phytoplankton, and similarly, if toxic metals like lead or cadmium at significant concentrations take different chemical forms, they’re more or less likely to affect organisms in a negative way.

How would you say your work impacts the public, or, what’s the larger significance of your work?

The direct significance of my research to the public lies in the importance of the oceans for moderating greenhouse gas concentrations on shorter and longer timescales and how that affects climate. So because algae, at the base of the marine food web, take up inorganic carbon and act to sequester it from the atmosphere and concentrate more of it in the ocean, but also because they can produce different sorts of greenhouse gasses, understanding what controls how much production -how much they grow -and the species composition that can affect things like greenhouse gas production ultimately depends on nutrient availability. So my research is looking to understand how some of these metal nutrients can affect their growth. Also, some of the metals that I focus on serve as tracers of ocean mixing and ocean productivity over time, so understanding how they’re distributed in the ocean and what processes control those distributions are important if we’re to understand how they’ve changed in the past and how sedimentary records of these metals can inform us about how the oceans participated in past instances of climate change.

So Jay, what’s your role in this particular GEOTRACES cruise?

So our role in this project is twofold. My research group here at sea, during the expedition part of the project, is responsible for providing trace metal and trace element clean samples for the rest of the GEOTRACES group. That involves deploying our trace metal clean rosette and filtering seawater samples and collecting other seawater samples for other members of the group. In terms of our scientific role, we’re making measurements of what are called bioactive trace elements. So these are metals, mostly in the transition row of the periodic table, that are again important for organisms as nutrients, or as potential toxins as well.

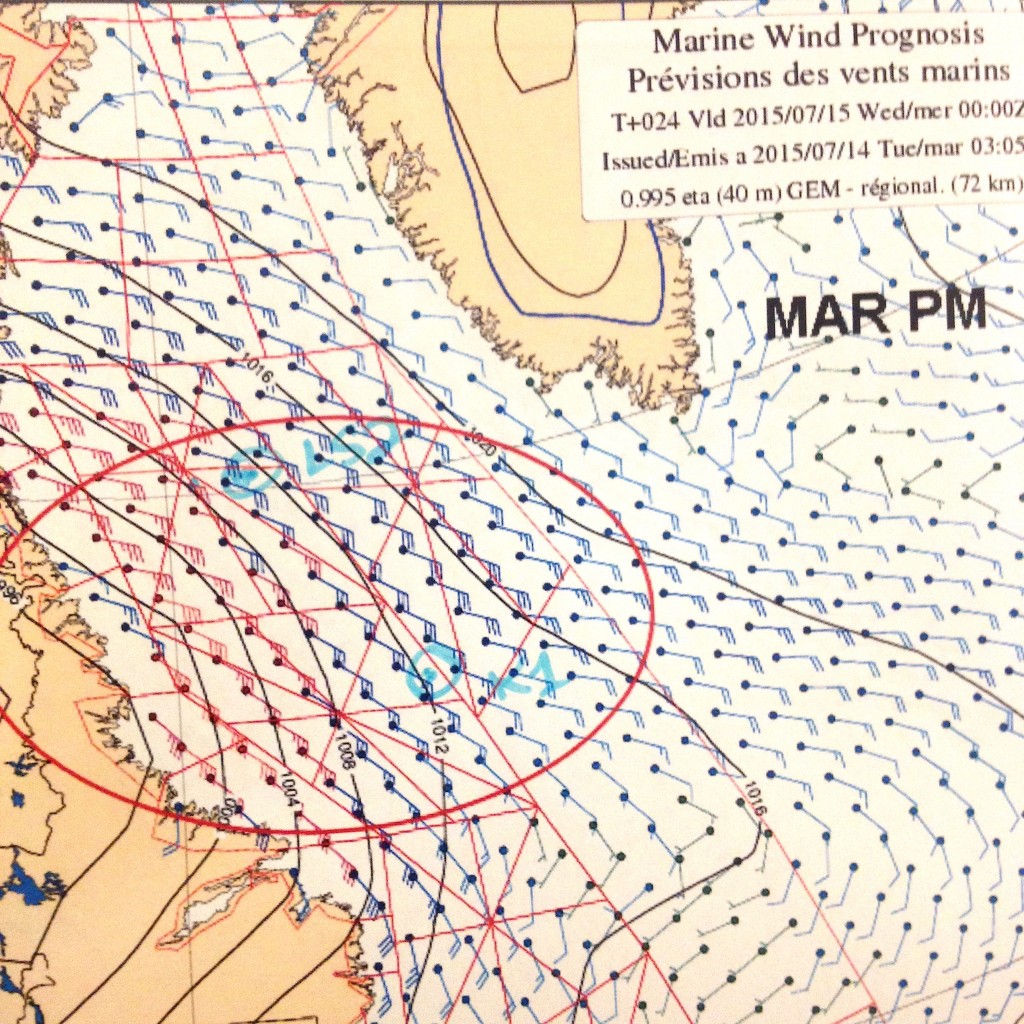

So why is specifically the Canadian Arctic a particularly interesting place to conduct your research?

The Arctic, in particular, is interesting because the impacts of climate change are being measured and experienced right now. The sea ice is a great example – it’s been melting and coming off so that seasonal sea ice extent has been diminishing over the past number of decades. The fresh water that’s being added to the Arctic affects the Arctic circulation and stratification and all these physical changes are likely to have biological and chemical impacts as well, and I think that’s one of the reasons why we’re seeing climate change sort of first hand, and why going to the Canadian Arctic is an important part of our research.

So now, speaking practically, how do you conduct your research in the field?

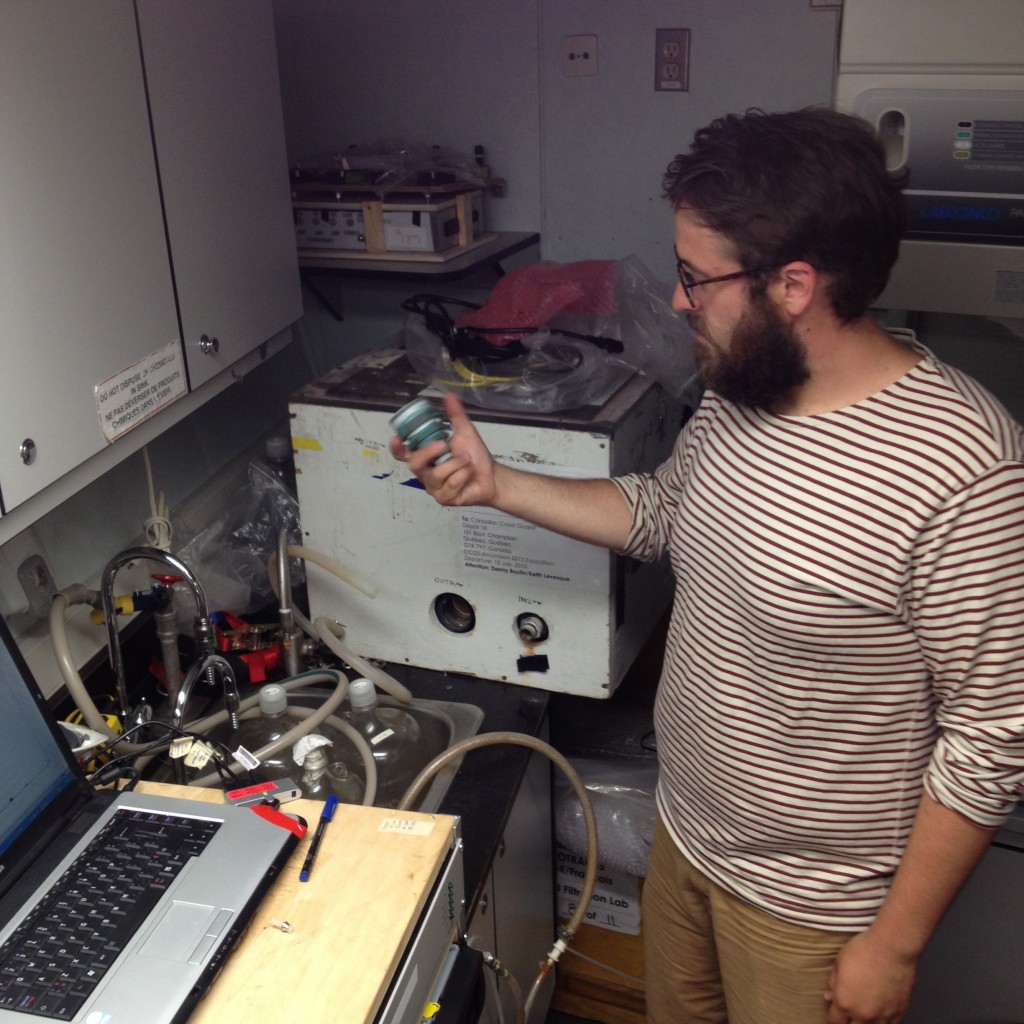

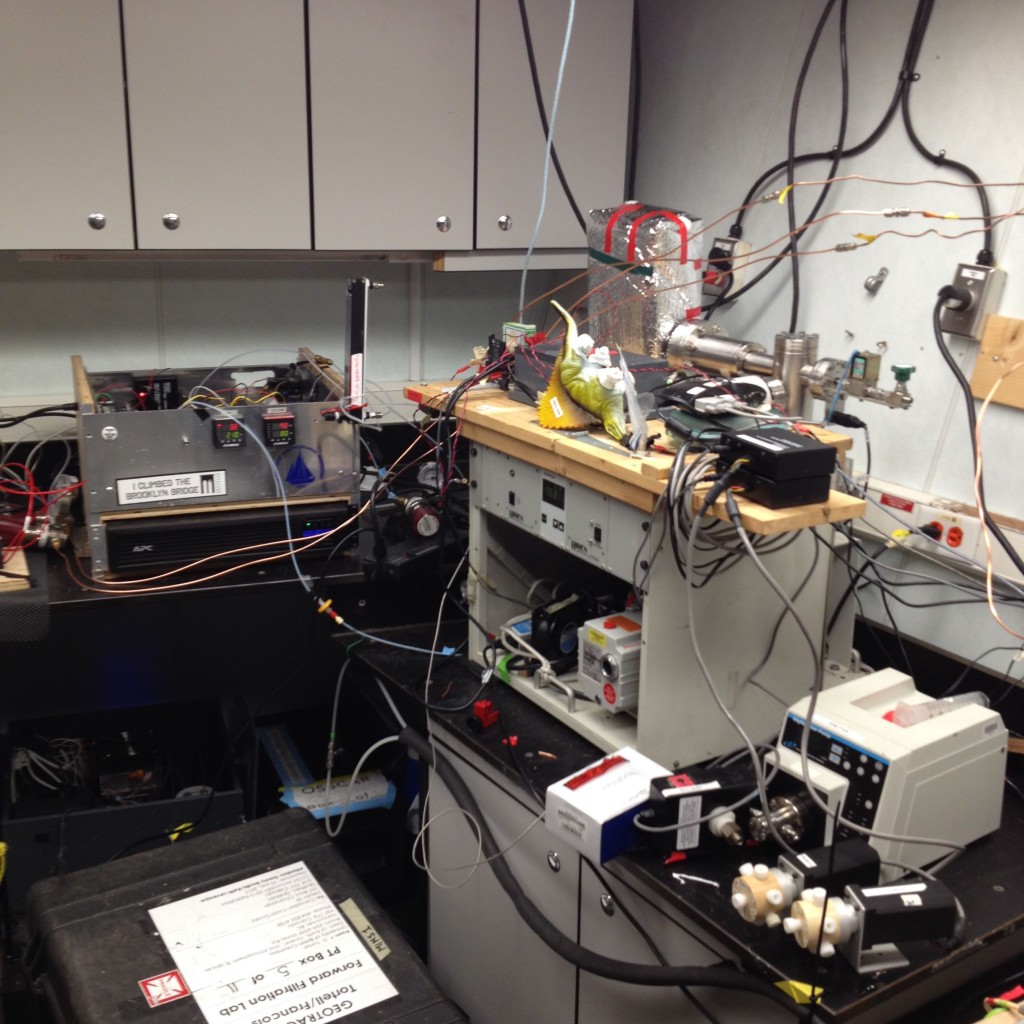

Research is challenging to conduct in the field, partly because we’re tasked with measuring these vanishingly low concentrations of some of these metals – their chemistry in seawater is such that there’s just not much of it there, on a very large metal ship, and so we’re surrounded by potential sources of contamination which can compromise our samples and therefore our results, and so we have to go to great lengths to keep our samples clean, so this involves using specialized equipment. But practically, we need to build clean environments within the body of the ship that keep particles and metals and grease and things from moving parts of the ship from contaminating our samples.

For that research, what sort of special equipment do you use?

We use a number of pieces of specialized equipment. Here to collect samples we use a water sampler that’s designed a little bit differently and uses special materials compared to a regular ship’s rosette, so we have an alumninium frame that’s powder coated to prevent contamination, a non-metallic sea cable that takes the instrument package over the side, and special bottles that are all plastic and teflon coated on the insides to make sure that our samples are clean. Just about everything that comes into contact with the samples and what we clothe ourselves with while we work is made of plastic to sort of limit that contamination.

But I understand that a lot of plastic has trace amounts of metal. How do you deal with that?

Well, almost everything we use needs to be thoroughly cleaned using very exacting protocols that have been established to remove this contamination. So we use a lot of detergent and a lot of mineral acids like hydrochloric acid to clean all these surfaces.

In your years as a researcher, what have been some of the most interesting realizations you’ve made, or, say, discoveries?

A lot of my work is focused on understanding a specific element in fact, cadmium, and how it behaves in the ocean. And this is because cadmium records in sediments help us to understand how the ocean’s changed in the past and how it contributes to modulating climate over time. And the work that I’ve been involved with with collaborating scientists has established that cadmium is removed from seawater by organisms. And certain organisms, diatoms, certain types of phytoplankton are able to use it as a nutrient element, whereas traditionally it’s been thought of as a toxin. So it was sort of a mystery, or somewhat confusing, that cadmium was distributed in the ocean like a nutrient despite having no nutrient function, and some of my work has contributed to helping understand why that’s the case.

Is there anything else you’d like to talk about to our listeners today?

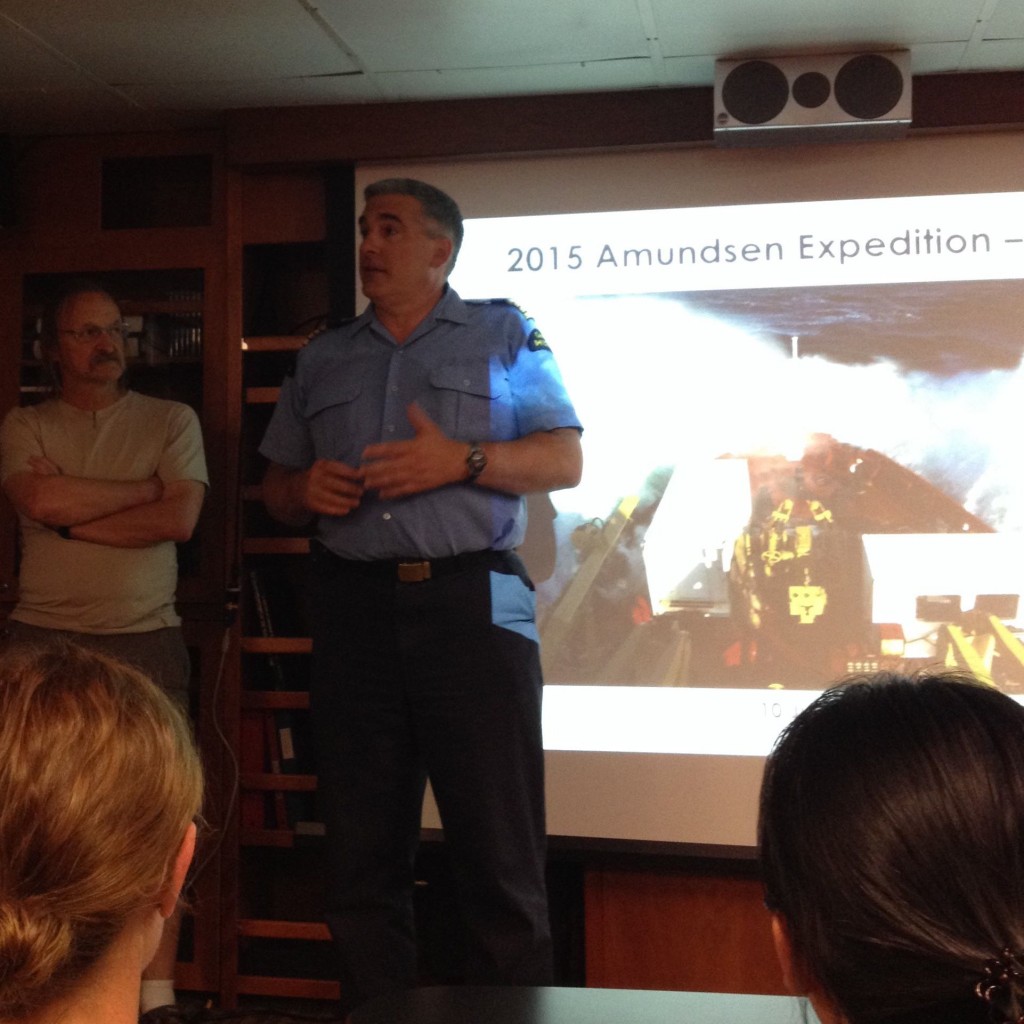

Well, I think I’d just like to highlight the importance of having research platforms like the Amundsen, so an icebreaker that’s capable of going to the high Arctic, and going to these important areas where we see these examples of climate change and how we can improve our understanding by visiting these places and conducting the sort of work that the GEOTRACES program, that’s funded by NSERC, allows us to do. So the captain and crew of this ship are a fantastic resource and really help us to get work done at these high latitudes. It’s very challenging, and otherwise we simply wouldn’t be able to do it.

Lastly, could you share an interesting or a strange fact about yourself?

Well an interesting fact I suppose is that I grew up in a more landlocked part of Canada, and while there were lots of lakes and rivers around that I was really interested in growing up, I really didn’t see the ocean until I was about eight or nine years old, except in movies and books and atlases, but I new I liked it the moment I saw it.

Thanks very much Jay, and good luck with your research.