Sophie Toor

At the Promise Institute’s Annual Symposium on Human Rights and the Climate Crisis at UCLA, over 250 leading lawyers, scholars, students, and activists gathered to strategize and analyze the increasing trend in litigation which seeks to frame climate change as a human rights issue. Keynote speaker Kumi Naidoo, endorsed efforts to make climate change justiciable by reminding the group that it is not the planet that is in danger, but humankind.

As the planet continues to warm, the impact on human rights is undeniable. This was recently affirmed by five human rights treaty bodies through a joint statement, explaining that “every additional increase in temperatures will further undermine the realization of rights”, and warning states to reduce emissions in order to comply with their human rights obligations.

Since the 2005 Petition to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights filed on behalf of all Inuit People living in the Canadian and American Arctic Regions pioneered the human rights litigation approach to climate action, over 30 cases worldwide have followed. Litigants are using both domestic, and international pathways to attempt to hold governments accountable for the human rights violations resulting from insufficient mitigation of the effects of climate change. However, it seems that environmental activists continue to hold their collective breath, waiting for that “one winning case” to set a precedent and form the basis for future successful cases.

Youth around the world are protesting and litigating for intergenerational climate justice. Photo credit Niklas Pntk/Pixabay.

Activists within several countries have achieved several notable successes domestically, such as the renowned Urgenda Case in the Netherlands, and the Colombian Desjustica Ruling. Although reason to celebrate, these two cases are not likely to spark a global effort to compel governments to act on climate change. The Dutch Supreme Court is considered quite progressive by other courts, and the Netherlands is not a top emitter of greenhouse gases. Urgenda may thus be less persuasive in other jurisdictions. The Colombian government has failed to fulfill court-ordered remedies, potentially undermining the significance of the Desjusticia legal finding. Perhaps the ruling we are all waiting for to spark a global movement for change will come from a court of a major carbon emitter, located in a jurisdiction with a stable political climate.

Canada is in a position to be a global leader on the issue of climate change. Not only is Canada among the top ten state emitters of greenhouse gases, but Canadian rulings may be highly persuasive in other common law jurisdictions. Several complaints alleging human rights abuses due to insufficient climate policy are currently pending in Canadian courts. Litigants combine various strategies such as alleging discrimination based on age and indigeneity, breaches to the right to life, liberty, and security, and breaches of the duty to make law for the peace, order and good governance of the nation. A ruling favorable to climate activists in Canada could be a major success and the “one winning case” we are waiting for.

Alongside domestic litigants, many activists seek to use UN treaty bodies to assert their rights are being violated by government inaction on climate change. Examples include the youth petitioners in Sacchi et al (a petition directed to the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child), and the Petition of the Torres Strait Islanders to the UN Human Rights Committee. The Human Rights Committee recently released a landmark decision, on a petitioner from Kiribati seeking asylum as a “climate refugee”. Although his claim was not granted, the Human Rights Committee confirmed that climate change poses a serious threat to the right to life that can form the basis of a future claim.

However, the usefulness of UN treaty body petitions may be limited in terms of producing a case that will make a meaningful difference. Many major carbon emitters are not parties to relevant treaties. Most notably the Human Rights Committee cannot receive individual communications alleging violations by the United States, China or India. Yet, there is still hope that the Sacchi or Torres Strait Islanders petitions will be highly influential and lead to changes in state action around the world. With this hope in mind, the question in the international field then becomes: which treaty body will take the first step forward?

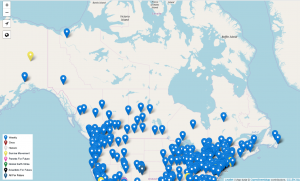

This screenshot is of a map created by #FridayForFutures which shows the weekly protests that happen in Canada, largely lead by youth activists.

With so many environmental activists courageously using domestic and international avenues to assert their rights, there is hope that the human rights approach will work. Perhaps rather than holding our breath for that “one winning case” to spark a global movement, what we really need is a wave of smaller, successive victories that happen simultaneously in different regions around the world.

Some legal scholars are hoping to tackle state accountability using other legal mechanisms. At the UCLA Symposium, experts considered whether states or businesses can be prompted to take meaningful steps to combat climate change through the use of international criminal law. In February 2019, the International Justice and Human Rights clinic released a report on prosecuting land grabbing as a crime against humanity. This report supports a compelling communication filed before the International Criminal Court on land grabbing in Cambodia. Like climate change, land grabbing is significantly connected to environmental degradation and human rights abuses. Criminal cases, however, require a higher standard of proof, which includes proving defendant’s criminal intent. Discussions are underway as to whether a new crime of “ecocide” should be introduced. Ecocide would target acts related to climate change, as well as other grave human rights abuses linked to environmental degradation.

Experts at the Promise Institute Symposium discussing the application of international criminal law to the climate change context. Photo Credit: Promise Institute Symposium

When discussing the introduction of the crime of ecocide, experts considered several preliminary questions. Will the value of creating such a crime be primarily symbolic or is it intended to be used to prosecute all major carbon emitters? Is it appropriate to hold both state actors and corporate actors accountable?

One perspective forwarded was that all that is needed to spark a movement of meaningful and urgent climate change mitigation is one criminal prosecution. The unfortunate reality is that corporations and states around the world are used to allegations of human rights abuses. Corporations in particular are routinely faced with threats of civil liability. Introducing the risk of international criminal liability may hold new weight as potential jailtime for individuals and reputational damage would be more likely to result in actual deterrence.

There would also be unwelcome notoriety to being the first company or country convicted internationally for ecocide. Following a first conviction, one can easily imagine the immediate and drastic reactions that may follow to avoid being next on the prosecutor’s list. Perhaps the “one” winning case we need is an international criminal case to spark meaningful and urgent climate action.

Sophie Toor is a 2L student at the Peter A. Allard School of Law, and is working with the IJHR Clinic as a part of the Environment Team.