Description of the Project:

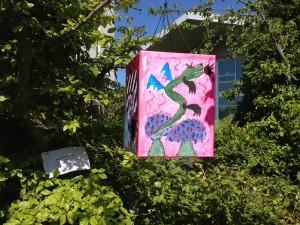

This project is an extension of our first project, the “Jabberwocky” hypertext poem. We decided to create a three-dimensional tetraptych inspired by the poem and our experiences working on its hypertext counterpart. Each of us has created a visual representation of “Jabberwocky” elements. Just as our online version of the poem brought together our individual interpretations of Carroll’s work, our art installation combines each of our visual representations into one large, four-part art piece.

In considering how to display this artistic adaptation to our peers, we discussed with one of our classmates the possibility of incorporating our project into his, which is a QR code “scavenger hunt” of sorts that will take place on UBC campus on the day of presentations. We created a QR code for our project that will take visitors back to the hypertext poem – the first iteration of our adapted “Jabberwocky” – when they scan it. We will have the QR code displayed near the artistic adaptation, and so the two will be able to function in tandem to enhance readers’ and viewers’ knowledge of Carroll’s poem.

Our Design Process:

Once again, we relied primarily on group brainstorming sessions. Our “Jabberwocky” hypertext poem was a completely digital endeavor which focused on opening a dialogue in order to create a collective understanding of a text. With this newest “Jabberwocky project,” we wanted to create something more tangible, so we decided to set aside our computers and create a physical art piece. However, we didn’t want to sacrifice the sense of fluidity that the hypertext poem embodied so well. In order to give our art piece the same sense of a “living text” that the hypertext poem had, we decided to attach the four canvas pieces together so that they form a hanging cube. This way, the piece retains a sense of movement and life reminiscent of the ever-changing hypertext poem. Indeed, our “Jabberwocky” tetraptych somewhat resembles a child’s hanging mobile — although, its rather twisted fairytale content might not be the most comforting visual to hang above a baby’s crib.1. What process did you use to develop your idea? Include any brainstorming prompts and approaches.

In order to present our project, we have placed our Jabberwocky in an outdoor setting. As mentioned before, we created a QR code to accompany our piece. It links to the first part of our project – the hyperlinked poem – so that viewers of the artistic rendering of “Jabberwocky” can easily access the words that inspired it.

2. What other pre-production strategies did you employ? For example, if you completed a video, to what extent did you “storyboard” and how did you develop the script? *Include any templates for storyboarding or other pre-production activities.

As this project was an extension of the first, it could be argued that the entire first project (our hyptertext poem) was a sort of pre-production strategy leading us up to the process of creating this second project. For each of our four canvas pieces, we worked independently and based our creations on our own interpretations of the poem. We knew only that each of us would use a variety of media (paint, crayon, felts, collage materials, natural materials, etc.) to create a visual representation of the Jabberwocky (either the beast itself or the poem as a whole). We had no idea what each of our pieces might look like and only saw them when we met together to put the whole piece together. We made sure that we purchased the same size and style of canvas to ensure that the structure of the piece would be uniform, unlike the styles and materials used on the canvas itself.

Similar to the two groups that presented their stop-motion videos, we encountered unforeseen obstacles in pre-production. For example, one of us (who shall r

emain unnamed) forgot her primary colours while purchasing acrylic paint at the dollar store and eventually realized that it is impossible to make orange paint without yellow paint. After a misguided foray into painting with mustard, it was decided that black fire, rather than orange fire, would be a compelling (and necessary) artistic statement.

3. How did you assign tasks or roles within your group? How did you manage time?

As it is a collaborative art piece, our roles were equal. We each purchased four canvas boards of equal size and set out to fill our blank canvases with our own visual representations of the poem. We each completed our quarter of the piece individually, and then we met together afterwards to put the pieces together. Other than our brainstorming meetings, our work was done individually on our own time. Furthermore, we used Google Docs to keep track of notes and to collaboratively complete all documentation.

4. What approaches would you use to assess this activity that take account of the following: a) the multimedia nature of the assignment; b) the collaborative nature of the assignment. *Include a draft assessment rubric.

Our experience with creating a rubric for the first part of our Jabberwocky project reminded us of the importance of valuing creative work as equal to “academic” work in our classrooms. As we’ve discussed in our class, too often, students who complete creative assignments are also required to give legitimacy to their work through text.

In order to give value to students’ creations for this assignment, we’ve decided to focus primarily on the process and not on the product. We’d ask students to keep a diary of some sort – text, visual, or otherwise – documenting their experience as they worked on their projects. The students would then be asked to present their projects and describe their experience and the results to the class. Finally, they would complete a self-evaluation and answer these questions:

1. Now that you have finished your project, what do you think worked well? Is there anything you would do differently if you were starting again?

2. Does your project accomplish what you intended? Why or why not?

3. Is there anything you think viewers of your creation should know that would help them better understand it?

Students would then give themselves a mark, focusing mostly on the creative process and their documentation of it, but also taking into account what they accomplished with their finished product. The teacher would also come up with a mark, and student and teacher would meet to discuss a final, collaboratively produced grade.

5. What are the greatest challenges in using this approach in a classroom and can they be ameliorated through careful instructional design? What learning opportunities does this activity afford? *Include a formal statement describing your goals in completing this assignment along with the drawbacks and affordances of the approach. All references and materials for this project should be included in a bibliography employing APA or MLA format.

We had difficulty thinking how best to translate the hypertext into a meaningful concrete medium and finally agreed upon the tetraptych as it allows for individual exploration of the poem’s content as well as a comparison across the group of just what the poem inspired in individual readers. Our biggest difficulty came when deciding on how to assess this project as giving a numerical mark for an artistic process can be challenging not only for the student (to self assign a mark), but also for a teacher who makes a value judgement when assigning a mark to a student’s creative work. Finally, we decided that a collaborative mark (one from student, one from teacher) that relies on the students’ ability to speak about the artistic process makes the most sense in evaluating a project that is centred around artistic merit and creativity.

In terms of opportunities – the students are able to begin their work in an online medium and translate it into a concrete form, while also turning their individual initial project (the hyperlinked text) into a group project. This allows students to compare and contrast their interpretations of a poem with their classmates. Often, projects go in the other direction (from concrete to online), so we thought it might be interesting to allow students to experiment with the reverse process (beginning with online and moving through to a concrete art representation).

Our goals for this assignment were to have students work through an artistic process of mounting a poem in a physical form; also, we aimed to have students use their online rendition of the poem and translate it into a physical form. Finally, we want students to be aware of the processes involved in creating thoughtful art, hence the questions asking students to self-reflect on the process of the project.

Thanks!

– Allison, Ilana, Ashlee, and Shannon