Entries Tagged as 'graphic novels'

Hi everyone,

Here is the Powerpoint (with article summary, description of our activity, and discussion questions) that we used for our seminar presentation on Graphic Novels and Visual Media. We deleted our Watchmen slides for copyright considerations.

– Katrina, Samantha, Zlatina, Dominic

LLED 368 – Seminar Presentation – Graphic Novels

Tags: graphic novels · Presentation

Some Suggestions for Graphic Novels in the English Classroom

- American Born Chinese — Gene Yang

- Gunnerkrigg Court — Tom Siddell (webcomic)

- Louis Riel — Chester Brown

- Malcolm X: A Graphic Biography — Andrew Helfer

- Maus I: A Survivor’s Tale: My Father’s History Bleeds — Art Spiegelman

- Maus II: A Survivor’s Tale: And Here My Troubles Began — Art Spiegelman

- Palestine — Joe Sacco

- Persepolis — Marjane Satrapi

- Red: A Haida Manga – Michael Yahgulanaas

- Safe Area Goražde — Joe Sacco

- Skim — Mariko Tamaki & Jillian Tamaki

- The Rabbits — John Marsden

- V for Vendetta — Alan Moore

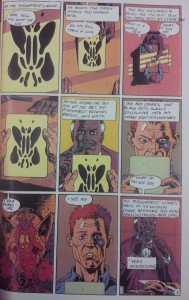

- Watchmen –– Alan Moore

Suggested Resources for Graphic Novel Study

Bakis, Maureen. The Graphic Novel Classroom: Powerful Teaching and Learning with Images. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, 2012. Print.

Bernard, Mark and James Bucky Carter. “Alan Moore and the Graphic Novel: Confronting the Fourth Dimension.” ImageText: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies Online Journal 1.2(2004): n. pag. Web. 20 Nov. 2009.

Carrier, David. The Aesthetics of Comics. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 2000. Print.

Duncan, Randy and Matthew J. Smith. The Power of Comics: History, Form and Culture. New York: Continuum, 2009. Print.

Eisner, Will. Comics & Sequential Art: Principles and Practice of the World’s Most Popular Art Form. Tamarac, FL: Poorhouse Press, 1985. Print.

“Graphic Novel / Comics Terms and Concepts.” ReadWriteThink. International Reading Association. IRA/NCTE, 2008. Web. 22 Oct. 2012. http://www.readwritethink.org/files/resources/lesson_images/lesson1102/terms.pdf

Heer, Jeet and Kent Worcester (eds). A Comics Studies Reader. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2009. Print.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: HarperPerennial, 1994. Print.

Meconis, Dylan. “How Now to Write Comics Criticism.” Dylan Meconis. 18 Sep. 2012. Web. 22 Oct. 2012.http://www.dylanmeconis.com/how-not-to-write-comics-criticism/

Weaver, John C. “Reteaching the Watchmen.” Graphic Novel Reporter. The Book Report, Inc., 2009. Web. 22 Oct. 2012. http://www.graphicnovelreporter.com/content/reteaching-watchmen-op-ed

—. “Who Teaches the Watchmen?” Graphic Novel Reporter. The Book Report, Inc., 2009. Web. 22 Oct. 2012. http://graphicnovelreporter.com/content/who-teaches-watchmen-op-ed

Wolk, Douglas. Reading Comics: How Graphic Novels Work and What They Mean. New York: Da Capo, 2007. Print.

Yang, Gene. “Graphic Novels in the Classroom.” Language Arts 85.3 (2008): 185-192. National Council of Teachers of English. Web. 22 Oct. 2012.

By: Katrina, Samantha, Dominic, and Zlatina

Tags: graphic novels · Presentation · Seminar Prompts

Tags: graphic novels · Uncategorized

Although Frey and Fisher advocate for the use of graphic novels and other visual media as a means of engaging students in creative writing, they nonetheless seem to situate these texts as something other than or outside of academic text. That is, while graphic novels may mediate learning through their pop culture appeal to students, they still seem to be presented as forms of “low-brow” reading and not as legitimate literary texts themselves. Invariably, the written text is still privileged; indeed, the authors’ focus was on using graphic novels, a “form of popular culture,” to “[scaffold] writing techniques, particularly dialogue, tone, and mood,” and even “[began] with the idea that graphic novels were comic books at best and a waste of time at worst” (24. This brings up questions of what exactly constitutes a legitimate and appropriate “academic text” for study in the English classroom and who has the power to make those decisions. Though this issue is beyond the scope of my post, I think these questions of legitimacy, access, and power imbalances in curriculum-planning bear further consideration.

To return to the article, while the authors’ focus seems to be on using students’ existing visual literacies to foster or reinforce more traditional forms of literacy, I would like to argue that not only should we treat graphic novels as literary texts in the classroom, but that we also need to explicitly teach visual literacy skills to our students. Although it is true that many students come into the classroom already possessing a different visual literacy skillset and perhaps have more confidence / practice in interpreting and encountering visual media, I think it is nevertheless important to give our students certain literary tools to enhance their reading, understanding, and analysis of graphic novels and their articulation thereof. Close reading and other analytical skills, after all, are transferrable across various literacies, and fostering students’ confidence and ability to analyze a graphic novel may also help them improve their analysis of more traditional forms of narrative, and vice versa.

Thus, I think if we are going to use graphic novels in the classroom, then we need to teach students the conventions of the discourse. At the very least, they should have an awareness of terminology and formal elements specific to graphic novel studies, elements that authors use to influence readers’ perception of the work. Just as students doing a film study need to be aware of certain aspects of film (such as camera angles, zoom, story boards, etc) that mediate or even manipulate our emotional reactions, so too, students studying a graphic novel need to understand elements such as framing, gutter space, panels, etc. In other words, students must be given the tools to understand not only what is on the page and what the effects of the page are, but also how these effects are achieved. The very nature of the graphic novel medium, after all, affects how we approach the narrative.

One significant difference between prose fiction and graphic novels, for example, is that graphic novels are a “unique hybrid of text and image” that demands a continuous shuffling of attention between the images and words (Rosen 3). Hirsch uses the term “biocularity” to highlight the “distinctive verbal-visual conjunctions that occur in comics,” and it is this biocularity that enables what Eisner termed “sequential art” (as qtd. in Whitlock 966). Specifically, sequential art conveys a story or information through presenting images in succession; however this “sequence of images [is] linked by juxtaposition, rather than chronological order,” and consequently, is able to “manipulate the time and space within a narrative” (Rosen 3). Thus, while capable of portraying a chronological account of events, comics are also able, at the same time, to depict simultaneous events by juxtaposing two different scenes. However, because comic panels are arranged side by side, there necessitates the existence of a “gutter,” or the negative space between the two images. These gutters, according to Whitlock, “fracture both time and space, offering a staccato series of frames” that require the reader to fill in the missing parts themselves and achieve narrative closure by “mentally [constructing] a continuous, unified reality” (970). Reading and analyzing graphic novels, therefore, require a different set of literacy skills, skills we should not automatically assume our students already have.

Works Cited

Frey, N. and Fisher, D. (2004). “Using Graphic Novels, Anime, and the Internet in an Urban High School.” The English Journal 93(3): 2004. 19-24. Print.

Rosen, Elizabeth, K. Apocalyptic Transformation: Apocalypse and the Postmodern Imagination. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2008. Print.

Whitlock, Gillian. “Autographics: the seeing ‘I’ of the comics.” Modern Fiction Studies 52.4(2006): 965-979. Project MUSE. Web. 20 Nov. 2009.

By: Katrina Lo

Tags: graphic novels

I do believe that using graphic novels in a class is a good idea. After all, as the Frey and Fisher article shows us, there may be great benefits! I think students are inherently comfortable with the genre of graphic novels because many have grown up with some comics (note: this doesn’t mean they necessarily have the tools to close- read and analyze them), but I do believe that since they are an element of the last few generations, there is something inherently ‘youthful’ and pop culture about graphic novels. They allow students to access similar themes that one can find in a novel, but they include a visual which adds a whole new dimension to meaning-making. What I find is the most pertinent question is: how does one find meaning at the intersection of text and image? To me, finding meaning of a text would be knowing the mood and tone, recognizing themes, interpreting the text in my own way, think of the text in a philosophical way, and being able to talk about/write about stories with similar themes. I do believe that graphic novels facilitate in finding this type of meaning in a text simply because of the visuals.

My major question is how can a teacher enable students to effectively read graphic novels. Essentially, what are the tools one can give students to be able t analyze the stories in effective way- to further find the ‘real’ meaning in them. Do we teach them about symbolism and how its represented? Do we talk about why certain panels are larger than others and why the gutter is a certain size? Personally, I have not taught a graphic novel yet. I understand their immense value, but I am left wondering how to best approach in a real classroom context.

Tags: graphic novels

Catherine Howes – Blog Entry #1

I think Graphic novels are highly under utilized in our classrooms at this time. I find they are a great way to get our students to enhance their critical thinking skills in a different way. Unlike novels, which often give descriptions of the settings, characters and their actions, graphic novels give you a version of the setting and encourage readers to decipher meaning from the artwork. Instead of listening to adverbs to describe how a character is doing something, you have to look at the picture to get that cue. It requires visual literacy to be able to pick up hints and understanding by looking at certain characters and how they are portrayed in a frame. It leads to questions such as:

1) Does the character’s actions/posture/place in the panel contradict the meaning of what he or she is saying?

2) How can you tell and what kinds of clues lead you to this analysis?

This becomes interesting when you get a classroom of students with different cultural backgrounds. Depending on where the novel is produced shares a large part of the cultural history of the writer, the time and place he or she is writing in and how you might perceive it. We interpret body language differently from country to country. While one student might interpret a character as being sincere because of their body language, another student may perceive it as a clear sign of deception based on his or her own cultural upbringing. This can foster discussions on whether or not there are certain types of body language that are cross-cultural. Through getting our students to look at the same panels, we allow them to show their critical thinking skills as well as allowing us to get a deeper insight into how they see the world.

By incorporating this type of text in our classroom we also help our ELL learners. Text on a page requires knowledge of a particular language; it requires a strong vocabulary and understanding of grammar. Pictures, however, give students the ability to gain understanding from pictures and then relate that to the words to infer meaning. By giving them a visual literacy to work with, we can help them make the connections between words and their meaning.

Tags: graphic novels

When I was on my practicum, I attended a pro-d day presentation on visual thinking strategies that showed me how effective still images can be in helping students learn what it means to provide an analysis. The presenter, a woman from an art gallery, showed us a very complicated and busy image. The room full of teachers were asked only three questions: “What’s going on in this picture?”, “What do you see that makes you say that?”, “What more can we find?”. After each comment, the presenter would repeat back comments neutrally while pointing to the area of the image being described, and linking the comment to other comments. I was skeptical at first, but in the end I was extremely surprised at how quickly everyone moved towards making analytical comments. Approaching the image with a sense of wonder ended up being a pretty unintimidating way to approach a text, and having the presenter, a knowledgeable art gallery employee, repeat back comments created a feeling of being understood and validated. I later tried this same strategy with my students and I found it to be equally as effective.

While I enjoyed the article by Frey and Fisher and while I was happy to see that they found success with using graphic novels with grade 9 students, I wondered if the students could have further benefitted from the visual thinking strategies I learned about. I love the use of creative projects in the classroom, but I think that using visual media lends itself well to helping students also build analytical skills and thus, academic writing and speaking skills. Then again, I also wonder if I am wrong and there’s plenty of analytical thinking happening that the article cannot sufficiently showcase because, oddly enough, there are no images in this article about graphic novels and anime.

My last thought when reading this article was about the quote “A barrier for school use [of graphic novels] is the predominance of violence and sexual images in many graphic novels” (20). What is it about imagery that makes it so much more unacceptable than sex described in a novel, or murders in a play? Many of Shakespeare’s plays have violence and sex, yet it is perfectly acceptable to read in school. Would a graphic novel of Hamlet be acceptable to read? If so, would it be because Shakespeare wrote it? If not, would it be because it’s worse to see the violence than to read it?

Tags: graphic novels

Christina Lee – Blog Entry #1

Graphic novels may somewhat appear to be a recent phenomenon, but images have been telling powerful stories for over 40 centuries. It is exciting to see the gradual emergence of graphic novels in more and more English classrooms. Engaging with graphic novels is definitely an effective way to help students build the visual literacy needed for them to be successful critical thinkers in the 21st century, a time where we are constantly bombarded by images with mixed messages. It is our duty as English teachers to encourage students to detach themselves from the perception that graphic novels simply provide “nice” visuals to the narrative, and start really looking at the images deeply and reading it as a part of the language of the medium. Ultimately, students can become more self-aware readers, especially in how they interact with the text by seeing their own and the author’s perspectives in conjunction with each other. Discussions will arise where students are able to make reasonable assumptions and challenge preconceptions in society. Graphic novels enable students to understand that expressing themselves and telling their stories are not limited to printed words on paper anymore, which will instill in them a newfound satisfaction and feeling of success in using images to convey ideas.

On a side note, another interesting type of graphic novel that may add a whole new dimension to visual literacy is the silent or wordless graphic novel, or simply, the picture book, as Shaun Tan likes to call them. Shaun Tan is an Australian author and illustrator known for addressing a multitude of social, political, and historical issues through his wordless books. I am an absolute fan of his work, and I highly recommend The Arrival, a story about immigration and the struggle to survive in the land of the unknown. Another thought-provoking story is The Lost Thing, which talks about a boy’s journey to finding the origin of this lost “thing” or “creature”. It has also been adapted into a short animated film (with minimal dialogue), and is equally brilliant. (Disclaimer: I shed many tears reading/viewing both of them.) I have shown both to students whom I tutor, and the way they were able to engage with it emotionally was phenomenal. The fact that the novels had no text and only had highly evocative images empowered my students and provided them with the agency to wrestle with the deeper implications, which often led to the creation of their own meanings. Students whose English was not their first language were able to enjoy it just as much as students who were native English speakers because they did not feel threatened by any vocabulary or grammar structures with which they were not familiar. We had a fantastic time going through various images and scenes, holding discussions pertaining to the various emotions they had experienced and how the images manipulated them to feel a certain way.

However, as valuable and useful graphic novels are in building English language skills in various innovative ways, that is not to say that graphic takes precedence over traditional texts, or that traditional texts should be replaced entirely. We should aim to integrate graphic novels in our English classrooms in such a way where the visual and the written can work in tandem, producing the best learning environment possible for students of all skill levels.

Tags: graphic novels

Shannon Smart – Blog entry #1

In “Using Graphic Novels, Anime, and the Internet in an Urban High School” by Nancy Frey and Douglas Fisher, the authors explore various ways in which these non-traditional media can be used to complement written texts and to encourage learning in a high school classroom. The authors posit that students – and particularly those that have struggled with reading and writing – are often bored by skill-building worksheets. North American schools, as well as schools elsewhere in the world, tend to privilege one style of teaching and one method of transmitting information high above others. Books, full mostly of small, typed words, are the medium of choice. Of course, reading doesn’t resonate with every person. Some learners, as Gardner (1983) has pointed out, are much more visual in the way they acquire knowledge. Others are tactile learners, while others, still, learn best when they hear new information. Many people, says Gardner, have “multiple intelligences.” With this in mind, Frey and Fisher’s suggestion that bringing graphic novels and the other aforementioned media into the classroom sounds like a darn good way of engaging students that are otherwise relatively disconnected.

My experience as a student teacher and a long time tutor supports Frey and Fisher’s hypothesis. I have seen that many students who struggle with reading and writing don’t simply need practice, but they need to try a different approach entirely. While it may sometimes be the case that an individual hasn’t mastered the skill yet and just needs a bit more time or assistance, I have found more often a struggling reader or writer needs to be provided with an alternate route to the destination. After all, learning to communicate, to tell stories, to empathize, and to think critically about texts (in the broadest sense possible: written or otherwise) aren’t skills you can just plug away at until you’ve got the rules memorized. They’re skills that take a great deal of time to master, and students with different learning styles will likely need different support as they develop them.

Not only does the use of graphic representation in school cater to students with different learning styles, but, as Frey and Fisher note, bringing graphica into the classroom capitalizes on many teens’ already-present interest in the genre. Additionally, bringing these “alternative” texts into the academic sphere legitimizes students’ personal interests. In my practicum, I used a graphic version of Romeo and Juliet as a supporting text (along with an audio recording by a group of actors in Stratford, Ontario, and two film versions of the play) while teaching Shakespeare’s early modern English text. A few times throughout the unit, I would give students a photocopied version of the same act from the graphic version after reading that act in Shakespeare’s original. I removed the text from the graphic novel’s speech bubbles and had the students try to fill in the gist of the characters’ conversations (in modern English) from memory before turning to Shakespeare’s words to find the right lines. The reactions from students were primarily ones of great relief. This was a grade 9 class, and many students had not seen Shakespeare before. Bringing the graphic version into the mix – I think – allowed them a familiar, safe medium to understand the play through. They had fun translating the lines into a more modern context to fit in the speech bubbles, too.

I should probably wrap this up. I suppose what I’d like to suggest, building off of Frey and Fisher’s work, is that in addition to using original graphic novels in the classroom, that all teachers – whether they enjoy reading graphic novels yourself or not – consider using graphic interpretations of canonical texts with their students. There are an ever-increasing number available. Frey and Fisher mentioned one that graphically represents some of Kafka’s short stories, but there are also versions of most of Shakespeare’s plays available as well as texts by Homer, Sappho, Milton, Melville, Dickens, Austen, Conrad, Woolf, Orwell…the list goes on and on.

Tags: graphic novels

Christopher Knapp, Weblog Entry #1

While I had considered the use of graphic novels within my own English language arts classes, what stood out to me most is how effective the use of graphic novels and/or other forms of visual text could be to ESL learners within the classroom.

In my prior experience with graphic novels, and in courses focused specifically on graphic novels that I took part in during my undergraduate degree, it also seemed as if graphic novels and the ability to ‘properly’ read a graphic novel required a degree of knowledge and expertise that was more advanced that what your average reader might possess; however, in reading this article, it came to my realization that while the degree of textual literacy and its difficulty might change depending on the graphic novel, the visual literacy and the skills necessary to interpret the images are such that it can be approached by almost any reader at any level (with the exception of small children). In this sense, what the article did most for me was change my perception of how one might read a graphic novel, and that it is possible to simply ‘read’ the story by simply viewing the images alone.

In relation to this idea of reading a graphic novel visually, rather than textually, I also found the use of graphic novels as a scaffolding tool to launch the students into a visually driven project/storyboard to be quite interesting, as it allowed students to effectively tell a story (through a series of pictures), without having to fully rely upon a strong textual narrative. In this sense, even for native English-speaking students, this kind of project has students thinking “outside of the box” in terms of what they are used to a story being, and in turn has them considering how they might tell a story through a visual mosaic; in a way, this allows students to tell a story through their own ‘eyes’, rather than their words.

Though Frey and Fisher happened to use graphic novels as their form of visual literacy in which to engage the students with, I think that this article raises the idea that any form of visual literacy, not just graphic novels, can be used as a means to engage students with English language learning and to increase their abilities not only in their language development, but also the skills needed to create and produce effective and meaningful narratives. With this in mind, I was left with the curious notion of what other forms of visual literacy might be effectively used in the classroom. Considering the ever-advancing growth of the Internet and Internet culture in the past two decades, might Internet comics, memes, or other visual materials be a more effective tool in which to engage our students? Though I have no definitive answer to this question, it is certainly one that I will continue to pursue in my own teaching practice.

Tags: graphic novels