Note: about a year ago Zack, myself, and a few other colleagues were asked to write a short, basic internal summary about badges in higher education. I realized that none of us had ever put it online. So here it is.

What is a Badge?

A badge is a digital symbol that signifies concrete evidence of accomplishments, skills, qualities, or participation in experiences (Educause, 2012). A digital badge typically consists of both a graphical icon and metadata about who earned the badge, the criteria for earning the badge, when it was issued, and who issued it. Thus a digital badge can provide a visual record of a learner’s achievement and development combined with the required proof (Glover, 2013). Furthermore, instructors and instructional designers can use educational badges to influence engagement and learning through the provision of focused goals, tasks, and affirmation of performance (Abramovich, Schunn, & Mitsuo, 2013).

A badge is a digital symbol that signifies concrete evidence of accomplishments, skills, qualities, or participation in experiences (Educause, 2012). A digital badge typically consists of both a graphical icon and metadata about who earned the badge, the criteria for earning the badge, when it was issued, and who issued it. Thus a digital badge can provide a visual record of a learner’s achievement and development combined with the required proof (Glover, 2013). Furthermore, instructors and instructional designers can use educational badges to influence engagement and learning through the provision of focused goals, tasks, and affirmation of performance (Abramovich, Schunn, & Mitsuo, 2013).

Once earned, the learner can display the badge to let others know of their skills mastery or learning accomplishments. In an “open badge” framework, learners accomplish this by adding the badge they’ve earned from different issuers to a “backpack”, which Glover describes (PDF) as an ePortfolio-type space where learners have control over how their badges are displayed and to whom. For example, learners can create custom groupings of their earned badges for sharing with different groups, such as different clusters for different employers related to the specific skills required or a different cluster for friends who share a particular hobby (2013).

The open educational badge movement is being lead by the Mozilla Foundation who is developing the interoperability technical and metadata standards needed to provide badge compatibility across different institutions, programs, and web platforms. Without a common badge infrastructure, badges would exist in silos, leaving little user control over how or where they may be issued and displayed. Instead, the Mozilla badge infrastructure enables learners to tie badges to their identity, to display their badges only to audiences they care about; to create meaningful collections of badges from different issuers, and to set privacy controls (Mozilla, 2012). The maturing of Mozilla’s open badge infrastructure in the last year has lead to the increased growth and interest in badges.

How Does It Work?

Badges in higher education can be used as a motivational tool as well as an alternative form of credentialing. Educause (2012) provides the following pathway as a basic model:

- An instructor or instructional course designer creates specific criteria for earning a badge.

- A learner fulfills the specific criteria to earn the badge by attending classes, passing an exam or review, or completing other activities.

- A grantor verifies that the specifications have been met and awards the badge, maintaining a record of it with attendant metadata.

- The learner pushes the badge into a “backpack,” a portfolio-style server account, where this award is stored alongside badges from other grantors.

- The learner can keep their badges private or display some or all of them on selected websites, social media tools, platforms, or networks

Furthermore, Mozilla (2012) states that educational badges are meant to be created and issued at different levels. For example, course level badges can be used for learner motivation, feedback, and gamification within a course and can be tied to learner behaviors or achievements. These course-level badges can provide the core or entry-level framework for acquiring skills and may be required as pre-requisites to unlock higher level badges. Institutional-level badges can then be used for certification purposes, which may be endorsed at an institutional level with more rigorous or defined assessments. Finally, multiple badges can be aggregated into higher-level “meta badges” that represent more complex literacies or competencies (Mozilla, 2012).

Who is Doing It?

Badges are a still an emerging pedagogical and technological tool for higher education. Purdue University recently created an open badge system called Passport, which is described as a “learning system that demonstrates academic achievement through customizable badges” (Purdue, N.A.). In describing the system, Gerry McCartney, Vice President for Information Technology at Purdue stated:

“Students learn in many ways and in a variety of settings while attending a university such as Purdue. In addition to formal lectures and homework, there is also time spent in labs and doing field work; time spent in service projects or internships; and experiences they glean from student organizations. The Passport app will give interested faculty and advisers another way to recognize and validate those skills for students. Through their college careers, students gain knowledge and skills that may not be well-represented in their college degrees. A student may have learned practical skills such as knowing how to write HTML code, have earned a prestigious scholarship or served as an officer in a student organization” (Watson, 2012).

Likewise, the UC Davis Agricultural Sustainability Institute (ASI) is currently developing a badge platform for validating experiential learning within formal institutional contexts at the undergraduate level. Various other universities, such as Carnegie Mellon and Duke, are also beginning to issue badges. A more comprehensive list is of educational badge projects can be found at http://www.hastac.org/digital-badges – projects.

What Does The Research Say?

Research into the use of digital badges in higher education is preliminary and still emerging. In a large-scale study on the use of Badges in PeerWise, an online learning tool, Denny (2013) found that badges “can act as powerful motivators in educational contexts of this kind and may be integrated with little risk into similar environments.” However, while Abramovich, Schunn, & Mitsuo (2013) found “evidence of improvements in interest and decrease in counter-productive motivational goals from a system using educational badges”, they also state that “the design specifics of educational badges in addition to the targeted students will be the main predictors of badge influence on learning motivation. The implication for instructional designers of badges is that they must consider the ability and motivations of learners when choosing what badges to include in their curricula.”

A comprehensive, annotated bibliography for educational badges can be found here: http://www.hastac.org/digital-badges-bibliography

How Could Badges Be Used at UBC?

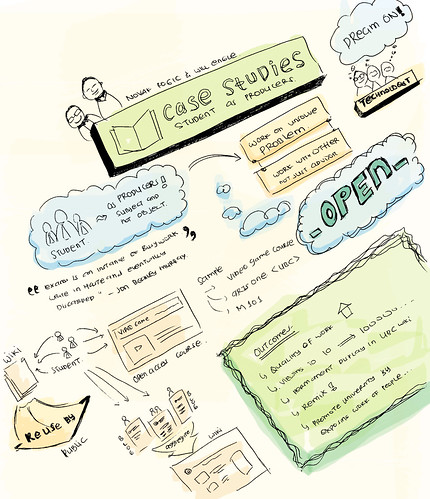

A priority of UBC’s flexible learning initiative is “the creation of a flexible continuum of learning between credit and non-credit” (UBC, 2013). UBC has long embraced online learning and with the recent attention to flexible and open pedagogies, interest and awareness in providing alternative methods of motivation and credentialing has also increased. Open, digital badges are a pedagogical and assessment tool that may be used at UBC for both motivating learners and providing alternative, pedagogical pathways.

Three models of how badges may be used at UBC include:

- As a student motivation tool within a course. For example, UBC’s Video Game Law course has proposed that issuing badges for specific course activities may increase student engagement. WordPress (CMS, UBC Blogs), MediaWiki (UBC Wiki), and Blackboard (Connect), have tools that could allow for badges to be used in courses.

- As a staff and faculty professional development tool, in which faculty and staff can earn badges for teaching and learning skills they have acquired at professional development events.

- As a tool for creating a personalized learning pathways across UBC courses and open educational resources. For example, professional programs may want to create badges that highlight competencies earned across courses. Additionally, developers of open educational resources may use badges as a way for life long learners to engage with their content

References & Resources

Abramovich, S., Schunn, C., & Ross Mitsuo, H. (2013). Are badges useful in education?: it depends upon the type of badge and expertise of learner – Springer. Educational Technology Research and Development. doi:10.1007/s11423-013-9289-2

Antin, J., & Churchill, E. F. (2011). Badges in social media: A social psychological perspective. CHI 2011, 1–4. Retrieved from http://gamification-research.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/03-Antin-Churchill.pdf

Cheng, R., & Vassileva, J. (2006). Design and evaluation of an adaptive incentive mechanism for sustained educational online communities. User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction, 16(3-4), 321–348. doi:10.1007/s11257-006-9013-6

Denny, P. (2013). The effect of virtual achievements on student engagement. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 763–772). New York, NY, USA: ACM. doi:10.1145/2470654.2470763

EDUCAUSE. (2012). ELI 7 Things you should know about badges. Retrieved from http://www.educause.edu/library/resources/7-things-you-should-know-about-badges

Glover, I. (2013). Open Badges: A Visual Method of Recognising Achievement and Increasing Learner Motivation. Student Engagement and Experience Journal, 2(1). doi:10.7190/seej.v1i1.66

Goligoski, E. (2012). Motivating the Learner: Mozilla’s Open Badges Program. Access to Knowledge: A Course Journal, 4(1). Retrieved fromhttp://ojs.stanford.edu/ojs/index.php/a2k/article/view/381

Grant, S. & Shawgo, K.E. (2013). Digital Badges: An Annotated Research Bibliography. Retrieved from http://hastac.org/digital-badges-bibliography

Halavais, A. M. C. (2012). A Genealogy of Badges. Information, Communication & Society,15(3), 354–373. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2011.641992

HASTAC. (2013). Project Q&A With: The SA&FS Learner Driven Badges Project Retrieved from http://www.hastac.org/dml-badges/SA%2526FS-Learner-Driven-Badges-Project

Ledesma, P. (2011, July 10). Can Badges Offer Viable Alternatives to Standardized Tests for School Evaluation? Education Week – Leading From the Classroom. Retrieved August 14, 2013, fromhttp://blogs.edweek.org/teachers/leading_from_the_classroom/2011/07/can_badges_offer_viable_alternatives_to_standardized_tests_for_school_evaluation.html?cmp=SOC-SHR-FB

Montola, M., Nummenmaa, T., Lucero, A., Boberg, M., & Korhonen, H. (2009). Applying game achievement systems to enhance user experience in a photo sharing service. In Proceedings of the 13th International MindTrek Conference: Everyday Life in the Ubiquitous Era (pp. 94–97). New York, NY, USA: ACM.

Purdue (n.a.) Passport: Show What You Know. Retrieved from http://www.itap.purdue.edu/studio//passport/

The Mozilla Foundation , a Peer 2 Peer University, & The MacArthur Foundation. (2012 8–27). Open Badges for Lifelong Learning. Retrieved from https://wiki.mozilla.org/File:OpenBadges-Working-Paper_012312.pdf

The Mozilla Foundation. (2012). Badges, FAQs. Retrieved from https://wiki.mozilla.org/Badges/FAQs

UBC (2013). Flexible Learning Priorities. Retrieved from http://flexible.learning.ubc.ca/what-is-flexible-learning/flexible-learning-priorities/

Young, J. R. (2012, January 8). “Badges” Earned Online Pose Challenge to Traditional College Diplomas. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/article/Badges-Earned-Online-Pose/130241/

Shield Icon by Benni from the Noun Project

![]() One of the trends at UBC that I’m excited about is the increasing support of the UBC Library for open education. I wanted to call attention to a couple of updates on the open front that are coming from the Library. First, the UBC Scholarly Communications and Copyright Office has posted new copyright guidelines for open courses and OER. As the introduction to the guidelines state:

One of the trends at UBC that I’m excited about is the increasing support of the UBC Library for open education. I wanted to call attention to a couple of updates on the open front that are coming from the Library. First, the UBC Scholarly Communications and Copyright Office has posted new copyright guidelines for open courses and OER. As the introduction to the guidelines state: