At the end of her lecture, Professor Hendricks challenged us to think about thinking of the sovereign as not-so-monsturous. This morning, Professor Crawford pointed out several times that Hobbes represents a far more modern way of thinking than Plato. He also had a lot to say about the paradoxical relationship between Hobbes and the liberal tradition.

Going into Hobbes, I at first dreaded it like I had with Plato. Plato’s views on authority and governance, though interesting, was hard to decipher and grasp as a real physical concept. Mainly the struggle was with his Kallipolis, Plato’s Ideal City that existed in his brain and described in The Republic.

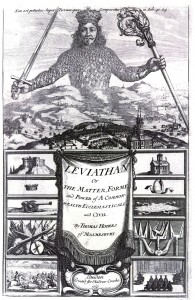

Hobbes surprised me. Not only did I enjoy much of what Hobbes had to say, but I also found myself nodding along as I read through Leviathan.

I liked Professor Hendricks’ challenge because whether you agree or not, I think there are benefits to Hobbes’ Leviathan. That is to say, if the sovereign is one that is just and good, wouldn’t the people lead a just and good life as well? Wouldn’t reforms be made in a much better and efficient way?

Let’s take, for example, Peron’s rule of Argentina.

He ran for presidency in 1946 and won, but in 1945 he’d pretty much secured that seat when he was released from military holding after only 8 days due to public pressure. This very closely relates to how Hobbes describes how the ruler is the representative of the people; and how, like Professor Hendricks had suggested, that the Machine (people) and the Monster (sovereign) works together.

Peron, like many other leaders in Latin America, began his presidency by dissolving other opposing governing parties, making Argentina a single party state. Not only this, he also held personal power over his own party.

Despite the singular control Peron had on the people of Argentina, the reforms he made benefitted the people (albeit only for a short period of time before the economy turned on them). Women were allowed to vote, hospitals and orphanages were built for the underprivileged, and working tools such as sewing machines were given away so that the average people could earn a living from home. All these reforms were made fairly quickly, and– like Professor Crawford mentioned in today’s lecture– allowed the people to live a good life, something that us as humans naturally want, according to Hobbes.

Peron’s rulership was described as “fascism with sugar”, a striking resemblance of the paradoxical relationship between liberty and authoritarian leadership. Peron was an authoritarian– a single party state ruler that decided what the people “shalt or shalt not do”, but he was also a liberalist in the sense that he provided equality and a good life to the people. He was not overly oppressive to his people; his most repressive law was perhaps the censorship of media.

Professor Hendricks’ challenge, in the scope of historical examples, is one that can be approached more easily if one could look at the benefits such a sovereign state can create for the people.