Ethnonationalists, Religion, and Violence

When adherents to Christianity, Judaism, Sikhism, Buddhism, or Islam commit violent acts in the name of a spiritual mission they are often responding to social, political, or economic grievances. What ever the specific motivating factors these advocates of violence often share highly charged misogynist and xenophobic views that resonates with social conservatism.

Reverend Michael Bray set fire to abortion clinics in the name of God, but also claimed that the U.S. government was undermining moral values. He was convicted of a string of bombings against women’s health care clinics providing abortion in the mid-1980s. He wrote A Time to Kill, a book offering religious justification for the murder of abortion providers. Bray also borrowed from Christian reconstructionist theology, an extremist subset of the already extreme Christian dominion theology. Reconstructionist Christians reject the separation of church and state and believe that Christians’ world domination is God’s intention.

Osama bin Laden sought the establishment of an Islamic state but was also protesting U.S. support for governments in the Middle East. bin Laden cut his teeth fighting with US support in Afghanistan against Russian occupying forces in the 1980s. While this Afghan conflict was presented as a free world versus communist oppressor struggle, the politics of the conflict on the ground were quite different. bin Laden and his allies were fighting to establish religious rule, not American style capitalism. After the Russians pulled out in 1989, from what many referred to as the Soviet Vietnam, the disaster left behind by a decade of civil war resulted din the rise of ultra-conservative religious leaders who were as opposed to capitalist styled liberties as much as they were opposed to Russian influenced modernity. Today Afghanistan is ruled by a male-centered religious group who used military force to take over control after the US and their allies withdrew.

Yahya Sinwar, 1962-2024, was a leader of the Islamist group Hamas who seek to establish an Islamic state in Palestine and Isreal. Before being killed by the Israel Defense Forces, Sinwar led brutal attacks against Israeli civilians. The International Criminal Court prosecutor filled for an arrest warrant against Sinwar in May of 2024 for the war crimes and crimes against humanity committed on the territory of Israel and the State of Palestine (in the Gaza strip) from at least 7 October 2023 which included murder, hostage taking, torture, sexual violence, and outrages on personal dignity.

Sinwar has been a part of the Islamist insurgency against the state of Israel since being a young man. He has been incarcerated by Israel many times for violence against Israelis. He was finally released from jail for good in 2011 as part of a prisoner exchange for an Israeli solder being held hostage.

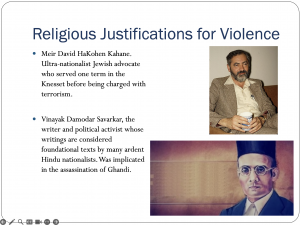

Meir David HaKohen Kahane; August 1, 1932 – November 5, 1990) was an American-born Israeli ordained Orthodox rabbi, writer, and ultra-nationalist politician who served one term in Israel’s Knesset before being convicted of acts of terrorism.

Kahane proposed enforcing halakha -Jewish rabbinical texts- and hoped that Israel would eventually adopt Halakha as state law. Non-Jews wishing to dwell in Israel would have three options: remain as “resident strangers” with limited rights, leave Israel and receive compensation for their property, or be forcibly removed without compensation. While serving in the Knesset in the mid-1980s Kahane proposed numerous laws, none of which passed, to emphasize Judaism in public schools, reduce Israel’s bureaucracy, forbid sexual relations between Jews and non-Jews, separate Jewish and Arab neighborhoods, and end cultural meetings between Jewish and Arab students. A political offshoot of Kahane’s movement is currently a minority partner in Israel’s current government.

According to Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, the writer and political activist whose writings are considered foundational texts by many ardent Hindu nationalists, the Indian nation is at its core a Hindu nation. A Hindu, in turn, is anyone who regards sovereign Indian territory as both their fatherland (pitribhumi) as well as holy land (punyabhoomi). Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, and Buddhists fulfill both criteria, while Christians, Jews, Parsis, and Muslims do not since members of these religious groups do not regard India as their true holy land. In the eyes of Hindu nationalists, India’s Hindu identity is important on its own terms and also because it has the potential to foster the kind of coherent national community needed for both social stability and global recognition.

Savarkar spoke favourably of facism in Germany, Italy, and Japan through the course of world war one. As the war progressed he started to explicitly draw references between the nazi policies toward jews as an example of how Indians should treat Muslims. When the atrocities committed by the Nazis became clear Savarkar did not renounce his affinity toward the nazis.

Each of these theorists shared a common belief in their religious/ethno-nationalist community as holding a kind of supremacy or divine dominion over a key geographical region, each were opposed to marriage outside of their circle of believers, each held views on the divine division between men and women in which men are the natural head of a traditional family. All of these shared beliefs are critical ingredients of a cultural view of society that justifies violence as natural and rightfully deployed on behalf of their cause.