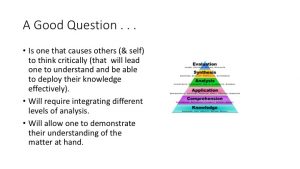

A Good Question

The idea here is that if one can generate a ‘good question’ from ones readings, listening to lecture or podcast, or watching video, one is well on the way toward effective learning. If one is able to pose a question, a question that engages with the material at hand, that integrates it across domains of thought, then one is really moving forward with understanding and being able to use the knowledge one gains.

The idea here is that if one can generate a ‘good question’ from ones readings, listening to lecture or podcast, or watching video, one is well on the way toward effective learning. If one is able to pose a question, a question that engages with the material at hand, that integrates it across domains of thought, then one is really moving forward with understanding and being able to use the knowledge one gains.

The good question exercise is one I often use in teaching. But more than that, it is an approach to learning and research that I use myself.

I try first to understand a piece of writing, say on a subject that is new to me or one that I might have a divergent perspective from the author. I am a strong believer in the efficacy of comprehension before critique. It is so easy to create a shopping list of all the things wrong with something I disagree with. It is more intellectually challenging to try and understand the logic, perspective, data, and argument of an author first. It will ultimately make any critique (positive or negative) more effective and nuanced in the long run. In my blog post ‘What does the prof want?‘ I discuss this approach in a bit more detail with an eye toward effective study technique.

Here is a standard set of instructions that I often use as the basis of a group activity in a class.

- Each group is to generate two or three ‘good’ questions based on the reading assignments. Take a few minutes -no more than five- to brainstorm ideas within the group. Write them down so that you can consider them. These ideas should not be fully formed questions.

- Next, review the ideas and begin to design questions from them. Ask yourself if the questions challenge you to think through the issues of fieldwork or do they help you understand the context of the two research sites. Be mindful that the answers must be in the readings and/or film. Also, the questions should not be designed to elicit opinion; they should require reference to information from the readings listed above.

- After everyone in the group has asked and discussed the questions revise and winnow the questions to two or three that you would be interested in presenting to the class.

- As part of this process you should also sketch out a brief answer to each of the questions.

- After finalizing the questions each group will present one question to the discussion group. At the end of this session hand in the questions and answers.

Whether used as a group activity, or an individual learning technique, the idea behind the good question draws upon a variation of Bloom’s Taxonomy. This is a kind of hierarchy of learning and knowledge. Imagine that the first step is simple memory and recall. Then we start to build comprehension. We apply our knowledge in some way. From there we start to analysis novel situations with our knowledge, link it together synthetically with other types of knowledge and then finally are able to evaluate (or critique our knowledge).

Whether used as a group activity, or an individual learning technique, the idea behind the good question draws upon a variation of Bloom’s Taxonomy. This is a kind of hierarchy of learning and knowledge. Imagine that the first step is simple memory and recall. Then we start to build comprehension. We apply our knowledge in some way. From there we start to analysis novel situations with our knowledge, link it together synthetically with other types of knowledge and then finally are able to evaluate (or critique our knowledge).

The good question approach is based on an idea of active learning – go beyond memory work- integrate the knowledge into one’s one understanding and make use of it. Doing it this way is one effective way to become a more proficient learner and ultimately a better researcher.