A Fathers’ Day Reading List for the New Year

When my own sons were young my partner gave me a copy of Patrimony by Philip Roth for father’s day. A little while later I came across an unexpected book by ecological anthropologist Ben Orlove, In my Father’s Study. These are books that have stayed with me.

The first is a tale of a son’s journey with a father at the end of his life.

The second is a story of a son coming to learn about his father, to come to an adult appreciation of him, after the father’s death. It’s a touching memoire. I’ve used it a few times in my teaching but my 20/30-something students respond to it rather differently than I. For them it is simply one more book on a reading list while for me it led me to think about my life as a father and as a son.

I’ve spent a great many hours with my own father. As a child following him around as he worked on his fishing boat. As a young adult working with him on the same boat. And later in life visiting with him, keeping each other company sometimes talking about the past, often about his health, and occasionally about my own work. Coming across Orlove’s book, almost by accident, has led me to gather over the decades an eclectic little library of books reflecting upon fathers and sons. Here, in sense of order, is a selection of my favourites.

- In My Father’s Study. Ben Orlove. U.Iowa Press. 1995

- A Life in the Bush: lessons from my father. Roy MacGregor. Viking, 1999. A loving tale of a northern Ontario father by one of Canada’s favourite journalists.

- Waterline: of fathers, sons, and boats. Joe Soucheray. David R. Godin, Publisher. 1996(1989). A memoire about restoring a boat, but its far more than that.

- For Joshua. Richard Wagamese. Anchor Canada. 2003(2002).

- To See Every Bird on Earth: a father, a son, a lifelong obsession. Dan Koeppel. Plume. 2006.

- Lost in America. Sherwin Nuland. Vintage. 2004.

- Patrimony. Phillip Roth. Touchstone. 2001.

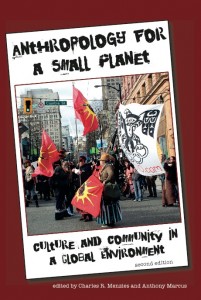

- My Father’s Wars. Alisse Waterston. 2013.

- Fatherless. Keith Maillard. 2019.

There are more – but this is more than enough for a start.