Late December brings the sound of jingle bells, carols, and grade appeals. It’s a seasonal thing that returns again just after the Easter Bunny has handed out chocolate eggs.

Let me first highlight the positive. Alongside of grade appeals, requests for clarifications or outright indignation, faculty also receive cards of thanks, emails of appreciation, and the occasional modest gift. There are students who make an effort to express their thanks for the opportunity to learn. These expressions are all very much appreciated. In fact, they go a long way to offset the worry we experience as faculty when the grade appeal season get started

Between the end of a course and the submission of final grades there is a brief moment of calm. There was a time when grades were posted on paper outside a faculty member’s office. The time involved in making one’s way back to campus to check the grade, separating the submission of a grade and a student’s awareness of it by days or weeks rather than minutes, allowed a period of reflection that forestalled rash responses. Email has created a more immediate reaction. I will often get queries mere moments after the grades are posted online.

In math, chemistry, or physics grades can be presented and determined with a more objective tone and complexion then seems to be the case in the social sciences. That said, most social science faculty members do use clear and transparent marking rubrics. Most of us make a serious effort to lay out evaluation criteria in our course outlines. But that doesn’t ever seem to stop the modest flood of critique and appeals that we receive around the end of term.

There are times when grading has been too severe (also too easy). In my large classes where I work with teaching assistants I make a point to ensure that from a meta level the grades produced by each marker are consistent across the entire class. I personally check low and high grades and a few in between from each individual marker’s portfolio. In classes that I mark myself I double check each grade assigned to ensure that I have been consistent. All this is to try to reduce any potential errors, omissions, or unfairness in marking. Just the same, there are almost always queries and occasional mistakes do slip in.

There are three basic approaches that students take toward grade appeals.

- There must be something wrong

- I am confused about how you arrived at my grade

- Can you explain how I could do better next time

Each of these approaches telegraphs a specific message.

The first approach is essentially an outright challenge (except in the cases when there is indeed something wrong). Students should use the first form of complaint sparingly. Check and double check before you speak to a prof with this approach. We are human and, as humans, do make mistakes from time to time. But proceed with caution.

“I am confused” is often a very sincere response. Typically the student who professes confusion has handed in work that is of middling quality. This is the normal type of work they do and for some profs they get good grades and others they get worse grades. Students have a right to feel confused. I share your confusion with colleagues who took the easy path, gave you a B+ or an A in their course, and thereby avoided having to meet with you to explain why they “only” gave you a C+ or B- (which very likely is what you should have been given). Truth is, we don’t do you any favour by giving you a high grade when what you really deserved was a grade that said good job, you met the criteria: C+. But in today’s world everyone wants an A (even if folks have forgotten what is involved in getting one). This is part of a grade inflation trend that is hard to escape from.

“Can you explain what I can do next time” has two variants: the sincere and the passive aggressive. The passive aggressive variant is a modified version of “there must be something wrong.” This student is concerned about upsetting the prof so settles upon the neutral “can you tell me what I could do next time approach.” Yet, lurking beneath the surface is a feeling that the prof did it wrong and the student wants her/him to figure it out and correct it. Unlike the sincere variant, the passive aggressive variant of this trope typically won’t relent and sometimes will, in a moment of exasperation, shift into the “there must be something wrong with how this was marked” style. The key indicator here is that the student will repeat a stock set of questions that inevitably circle back onto their idea that their paper was not correctly evaluated.

The sincere student is trying to figure things out. They are less interested in the grade then they are in learning the material and how to be an effective student. They may simply not understand how to differentiate between a modest quality of output and a high quality of output. The sincere student may also confuse the quantity of labour invested into an assignment or studying with the quality of time (in fact many studnets make this mistake). There is a useful concept called “socially necessary labour time.” Defined as: “The labour-time required to produce any use-value under the conditions of production normal for a given society and with the average degree of skill and intensity of labour prevalent in that society.” What does this have to do with grades? Simple: quantity of effort expended does not equal quality of output produced. That is, one doesn’t deserve a high grade simply because one spent the most time they ever had doing this assignment. The trick is to balance the amount of work required with the desired outcome in a way that conforms to the standard quantity of time a competent student spends completing a particular assignment.

Ultimately focusing on grades deflects a student from the fundamental idea of learning. It is a lot to ask of students (given our societies’ hyper-concern with evaluation, ranking, and grading) to focus on learning as opposed to grades. Why should a student be any different then other people – grades are unfortunately seen as measures of worth and as a kind of capital used to buy privileged positions in society? My answer is that learning is not always reflected in grades. Ideally I would remove scarcity based grading (which is what I call current models) and shift to a more qualitative form of assessment that measured a students learning in terms of how their understanding of a subject evolved, where did a student start? How has their understanding and knowledge expanded? What new process skills have they learned? Can they demonstrate these new skills and new understandings in novel settings? Grades are one small measure and a decade or more after this class is over I doubt a student will remember the grade they got. They might recall a classmate, a discussion, a particular reading or lecture. That is ultimately what is most important.

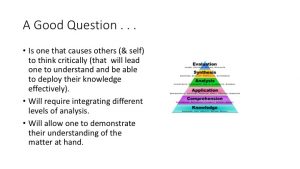

The idea here is that if one can generate a ‘good question’ from ones readings, listening to lecture or podcast, or watching video, one is well on the way toward effective learning. If one is able to pose a question, a question that engages with the material at hand, that integrates it across domains of thought, then one is really moving forward with understanding and being able to use the knowledge one gains.

The idea here is that if one can generate a ‘good question’ from ones readings, listening to lecture or podcast, or watching video, one is well on the way toward effective learning. If one is able to pose a question, a question that engages with the material at hand, that integrates it across domains of thought, then one is really moving forward with understanding and being able to use the knowledge one gains. Whether used as a group activity, or an individual learning technique, the idea behind the good question draws upon a variation of Bloom’s Taxonomy. This is a kind of hierarchy of learning and knowledge. Imagine that the first step is simple memory and recall. Then we start to build comprehension. We apply our knowledge in some way. From there we start to analysis novel situations with our knowledge, link it together synthetically with other types of knowledge and then finally are able to evaluate (or critique our knowledge).

Whether used as a group activity, or an individual learning technique, the idea behind the good question draws upon a variation of Bloom’s Taxonomy. This is a kind of hierarchy of learning and knowledge. Imagine that the first step is simple memory and recall. Then we start to build comprehension. We apply our knowledge in some way. From there we start to analysis novel situations with our knowledge, link it together synthetically with other types of knowledge and then finally are able to evaluate (or critique our knowledge).