James (Jim) Andrew McDonald

‘Wi Goot (Ph.D. UBC 1985) b. 1951 – d. 2015

I first met Jim in the early 1990s. I think it was around a seminar at the North Pacific Cannery, but I can’t be certain. Funny thing is that I feel as though I had known him for much longer. It is, in fact quite possible that Jim and I had crossed paths in the decade or so before I first ‘knew’ him. I am a member of the Indigenous culture group that Jim made his life’s work to study. I knew and interacted with many of the same people, or least same families, that his work and friendships brought him into contact with. I do know that by the time I was serious about my academic work I knew Jim and his work.

According to Jim his research, starting in 1979, involved a “happy coincidence: Kitsumkalum Band Council decided it wanted an anthropologists to make a study of their social history that would assist them in their land claims and economic development. Since I [McDonald] intended to do an historical study of the political economy of an Indian population, our paths came together in a mutually beneficial way” (1985:22). From the start Jim’s work was a collaboration between the leadership of the community and himself. This was part of a new wave of engaged anthropology that had its roots in Kathleen Gough’s call for new proposals that placed anthropology at the service of colonized peoples (Gough 1968; see also, Menzies and Marcus 2005). As Jim noted he “usually met with people as a representative of Kitsumkalum Band Council, although the connection between [his] work and theirs was not clear cut” (1985:24). Upon completion of his dissertation McDonald worked for a decade as curator of ethnology at the Royal Ontario Museum. In 1994 he was hired by the University of Northern BC to take over chairship of First Nations Studies.

Jim’s work combines a detailed Marxist understanding of colonial oppression, industrial resource extraction capitalism, social class, and combines that with a fine grained understanding of the Tsimshianic intellectual and cultural tradition. This is an amazing accomplishment. Jim achieved by valuing Indigenous communities: he did not use us as laboratory or some source of data. Rather, his approach involved an explicit collaborative framework. Jim was not simply an outsider anthropologist knowledgably in Indigenous matters. He became a trusted insider.

McDonald’s form of collaboration created a space for the co-generation of knowledge. That is, working on projects defined and requested by Kitsumkalum McDonald was able to focus his research in ways that would illuminate issues and perspectives relevant from an Indigenous perspective. At the same time his theoretical framework (political economy) and engagement in the academic arena brought insights to community understandings on their own social history that would not necessarily have been the case had they simply hired a consultant.

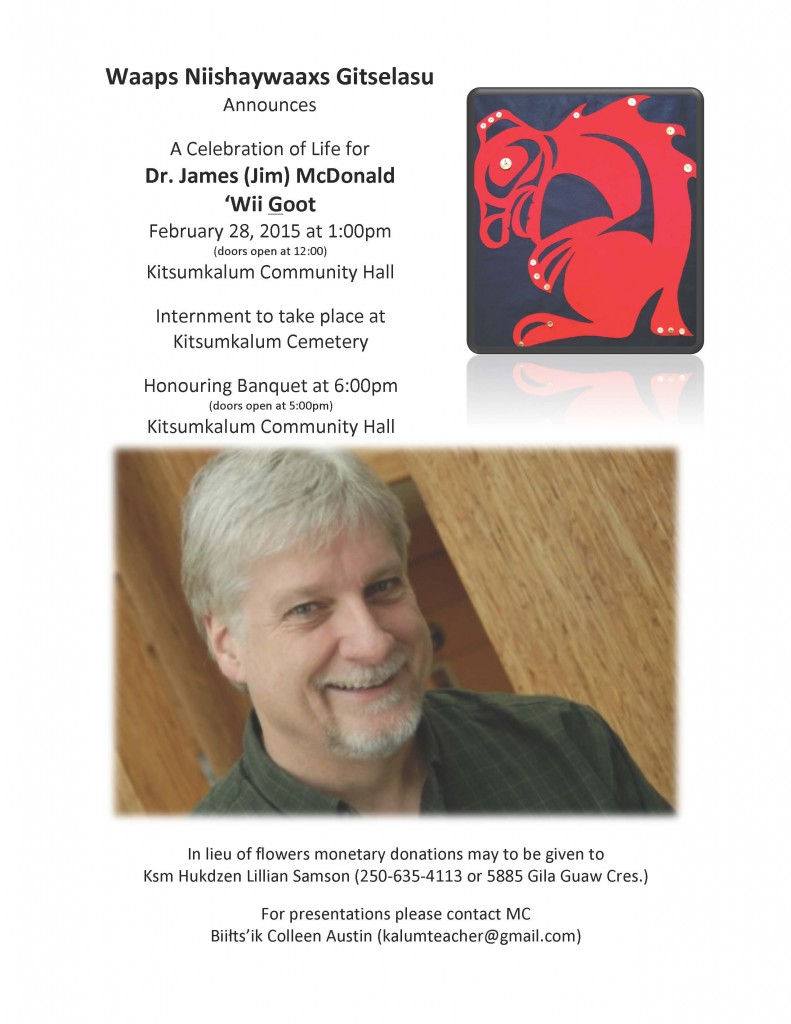

At the end of his life Jim came home to Kitsumkalum. His funeral and honouring Banquet was hosted Waaps Niishaywaaxs Gitselasu. His life’s work lives on through the work of Jim’s many students, friends, and family members.