A UBC School of Anthropology?

Could there be a UBC School of Anthropology? That is an interesting question. As one of the top ranked anthropology departments in Canada one may well like to think there is something unique about our program and some quality and impact among our members past and present. But rankings, desires, and aspirations do not make a school. What might be the core aspect of such a school of thought if one could be said to exist?

Harry Hawthorn founded UBC’s anthropology department in 1947. Under his direction the department produced volumes of theses and dissertations concerning Indigenous peoples in Canada. While the department’s research focus has expanded geographically, we do retain a strong cohort of faculty and graduate students working with and among Indigenous communities in Canada and abroad. Our program is also entwined with the Museum of Anthropology, founded by Audrey Hawthorn in 1949. However, though some of the Museum’s faculty are co-appointed in anthropology, not all of them are and the Museum is a stand-alone institution with it’s own institutional character and mandate. As with the department, the museum has a strong focus on research with and among Indigenous communities.

There are at least four strands of work emerging out of UBC Anthropology’s engagement with Indigenous-based research: an empirically-based tradition of ethnography linked to provision of expert testimony, an empirically-based traditional of field archaeology, a structuralist Levi-Straus influenced ethnographic practice, and a materialist tradition of political economy. These are not hermetically sealed categories and colleagues may not necessarily agree with this grouping, but when one examines closely the corpus of our department’s publications relating to Indigenous communities on the north west coast of North America one can clearly see these general streams of work.

Under Harry Hawthorn’s direction several decades of empirically grounded graduate studies of Indigenous communities were produced. Hawthorn himself led two major government funded projects “The Indians of British Columbia: a study of contemporary social adjustment” (Hawthorn, Belshaw, and Jamieson 1955) and “A Survey of the Contemporary Indians of Canada (Hawthorn 1966). These, and other similar reports, examined the socio-economic state of Indigenous peoples with recommendations for accommodating Indigenous peoples within the mainstream economy.

Hawthorn was not alone among his colleagues of the day in engaging in applied, policy, or expert witness research (see, Kew 2017 for his personal reflection on a history of applied research). Wilson Duff, whose work was pivotal in making William Beynon’s fieldwork accessible to several generations of students, was a key expert in the Nisga’a land claims, commonly called The Calder Decision (Forster, Raven, and Webber, 2007). Duff, who worked at the Royal Museum of BC before taking up an appointment at UBC was a thorough empirical researcher interested in not simply what was, but also how Indigenous communities found their way in the contemporary moment. Michael Kew, who began teaching at UBC in 1965, already had amassed a strong history of applied anthropology before he began at UBC. With a BA from UBC (where he had studied with, among others, Harry Hawthorn) Kew found work with Duff at the BC provincial museum in 1956 (Kew 2017). From the museum he went to work for the Centre for Community Studies, University of Saskatchewan. He returned to graduate studies in 1963 in the doctoral program in anthropology at the University of Washington (PhD completed 1970). All the while his work focused understanding the ways Indigenous communities persisted and adapted in the face of fundamental social transformation.

These early members of the department were trained in an anthropological approach the prioritized detailed empirical fieldwork with community-based knowledge holders. Their work involved both a consideration of historical practices predating colonialism and the contemporary adaptations of Indigenous peoples (see, for example Hawthorn 1966; Duff 1964). Closer in sensibility to the British structural functionalists than with Boasian particularism, they were very much interested in how things worked and how change wrought by colonialization emerged within the contemporary period.

Archaeology was not originally part of the anthropology program at UBC. Instead, an amateur archaeologist and Germanic Studies professor, Charles Borden, initiated it (West 1995). “In the 1960s Borden would reflect that Drucker’s words [see Drucker 1943:128] … instigated his early amateur involvement in B.C. archaeology: ‘Drucker’s report … had a profound influence on the present writer. It was the direct impact of his publication which in 1945 prompted me to initiate a series of salvage projects at potentially important but rapidly vanishing sites within the city limits of Vancouver.” (quoted in West, 1995:6-7). Wilson Duff had been an undergraduate student of Borden’s. Working together in the 1940s and ‘50s, Borden and Duff conducted some of the earliest scientific archaeology in the province. They also joined with the Musqueam Indian Band in 1946 to initiate one of the earliest archaeological partnerships between a university and a First Nation in the province (Roy 2006). Later, as an employee of the provincial museum, Duff created the journal Anthropology in BC that came to play an important role in the professionalization of archaeology in BC (West 1995).

Duff, Hawthorn, and Borden collaborated in establishing a provincial research program that linked social anthropology and archaeology. Duff, from his position at the provincial museum “sent Borden and his UBC colleague, Harry Hawthorn, a series of recommendations based on the assessment that provincial archaeological sites were in danger of destruction, by both urban expansion and proposed hydro electric dam projects (West 1995:27). They also coordinated in having legislation set in place to regulate and professionalize archaeological excavation. They also lobbied to have developers, not the government, pay for the cost of archaeological research (West 1995:27). A decade of lobbying resulted in the passage into law of the Archaeological and Historic Sites Protection Act in 1960, the forerunner of today’s Heritage Conservation Act.

As West observed the early UBC anthropological tradition (circa 1945-1970) closely linked socio-cultural anthropologists and archaeologists in a common pursuit of the scientific study of Indigenous peoples in British Columbia (1995). These foundational figures of the UBC School placed a higher value in scientific study than they did in the beliefs of their Indigenous research collaborators – at least in terms of historical truth. Duff’s and Kew’s expert opinion research, for instance, relied upon interviews with Indigenous knowledge holders to document historical practices but they also drew upon archival records and archaeological and (in some cases) ecological data to triangulate their conclusions.

The mid-twentieth century anthropological stability was shaken by the rise of new ideas in the academy ushered in on the tails of national liberation struggles in the heartland of anthropological fieldsites (Latin America, Africa, Asia, and Indigenous North America) and the new social movements of the metropole (Patterson 2001). At UBC these changes first appeared in the form a Marxist influenced political economy (the later more evident among the students than the faculty) and a theoretical interest in Levi-Strausian structuralism.

Marxist influenced political economy had few faculty adherents in anthropology at UBC, most of the Marxist influences came from new hires in the sociology side of the program (circa 1970s). There were other materialists and empiricists within anthropology in the form of archaeologists and carryovers from the Hawthorn-Duff period, but they were not necessarily advocates of Marxist theory. The most explicit political economists were among the graduate students.

Between 1977 and 1995 five dissertations (Kobrinsky 1973, Pritchard 1977, McDonald 1985, Boxberger 1986, Littlefield 1995) and at least three MA theses (Wake 1984, Legare 1986, McIntosh 1987) engaged in some significant way with Marxist influenced political economy (though the authors may well eschew a Marxist label). There were additional theses, such as Sparrow’s (1976) work and life history of her paternal grandparents or Brown’s (1993) analysis of Indigenous cannery work that, while not specifically political economy, did engage with a common subject matter (labour, labour organisation, and working class experience).

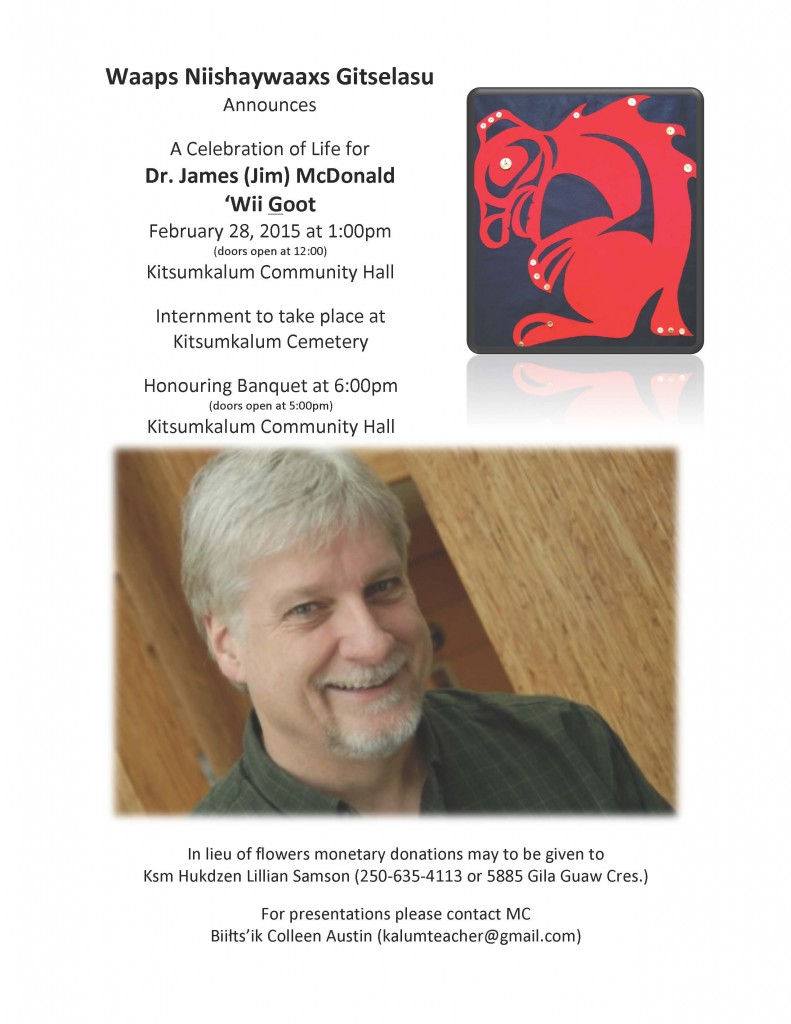

The political economists, though considerate and respectful of Indigenous community sentiments, were also interested in documenting processes of change and transformation and analyzing such change in the context of a theoretical model external to Indigenous systems of knowledge. Pritchard examined how Haisla involvement in the industrial capitalist economy undermined their traditional social organization. McDonald analyzed how the development of industrial resource capitalism in north western British Columbia simultaneously underdeveloped Kitsumkalem’s Indigenous economy. Boxberger’s dissertation also examines the way the Lummi’s incorporation within a capitalist economy served to disadvantage them vis-à-vis their access to elements of the mainstream capitalist economy. Littlefield differs from the other three with an explicit feminist analysis in her study of Sne-nay-muxw women’s eemployment, though she too is interested in how this Coast Salish community was incorporated into the capitalist economy. In each of these cases the notion of truth was not so much about the truth vested in Indigenous oral narratives, but the truth of specific transformation in material conditions of life and how that was shifting Indigenous social and cultural organization.

The structuralist approach, represented on faculty by Pierra Maranda, and among graduate students by people like Marjorie Halpin (1973; who became a faculty member in 1973), Martine Reid (1981), and Dominque Legross (1981), had an effervescence quickly displaced by the growing interest in interpretive and post-modern anthropology, a tendency that has gripped mainstream anthropology for several decades now (in various and often competing, forms). The French structuralist moment was driven by Levi-Straus’s ideas of binary oppositions and the notion that the meaning of ritual, myth, and cultural institutions did not reside in what people said they were but were rather notions that emerged from the structure of mind. While key local knowledge holders were valued – the analytic frame was one that located meanings and truth somewhere other than the surface statements. The French structuralists did not accept that Indigenous oral history was in any way a true history (or that historical truth was of central importance); for them, the truth lay in what the ‘myths’ revealed about structure of mind.

This kind of structuralism was fairly short lived, compared to other approaches within anthropology, and was replaced in the 1980s and 1990s with a discourse, narrative, and community-focussed kind of anthropology. While the externalist idea of applying theories and models to Indigenous peoples, narratives, and communities continued, now it was done with an eye toward giving ‘voice to the voiceless.’ These developments occurred within the context of a discipline that was turning to a consideration of how one might write as being as important (if not more so) than what one might write about (Marcus and Fisher 1986). The earlier empiricism of UBC’s founding anthropologists was gradually being displaced by a more post-modern (Marcus and Fisher 1986) or cultural studies approach that was less interested in interrogating knowledge holders as to the veracity of their statements and more interested in revealing and celebrating internal cultural logics and expressions.

Even with the post-modernist turn Anthropology at UBC continued to be primarily driven by theoretical frames and models that saw Indigenous peoples and communities as a source of data to apply their external theories to. Clearly the works of UBC anthropologists such as, but not limited to, Michael Ames, Julie Cruickshank, Bruce G. Miller, or Robbin Riddington demonstrate a deep-seated respect for Indigenous peoples and societies. Yet the concerns they focus on, while respectful and imbued with an Indigenous sensibility, were not slavish beholden to a literalist interpretation of Indigenous narrative. These are scholars who engage with real Indigenous communities, consider their perspectives, and apply their academic training to making sense of the actually lived worlds of people they care about. Respectful research has deep roots at UBC.

Leona Sparrow, currently Director of Treaty, Lands, and Resources, Musqueam, described the importance of documenting Indigenous perspectives of work through a life and work history of her paternal grandparents (1976:1-4). In the opening section of his dissertation, James McDonald (1985) describes the process of gaining permission to conduct research with Kitsumkalum First Nation.

“At the time when I was considering specific topics and seeking a study area, there occurred a happy coincidence: Kitsunkalum Band Council decided it wanted an anthropologist to make a study of their social history that would assist them in their land claims and economic development. Since I intended to do an historical study of the political economy of an Indian population, our paths came together in a mutually beneficial way. A relationship developed between the Council and myself in which the Band Council provided me with contacts, material support, guidance, and encouragement that not only facilitated the study greatly, but also lent it an orientation that incorporate Indian as well as academic expectations” (McDonald 1985: 22).

Sparrow’s approach prefigures, and defines, what UBC anthropologists can clearly claim as one of the core attributes of their Indigenous-focussed research. McDonald’s dissertation show the practice in full form: respectful of community expectations, field-based, focussed on long term relations that take into account Indigenous perspectives while being firmly rooted within the protocols of scholarly discipline-based research. Members of the UBC School may well approach research questions from different theoretical perspectives or personal experiences, but do so from a common commitment to respectful fact-based and community-grounded research.

The UBC School, if one can be said to exist, can be summed up as our colleague Bruce G. Miller has recently done: “The persistent theme at UBC, … for all of us, independent of where we were trained, was engagement and the department decided around 2014 that the collective identity was of “grounded” researchers, whose research questions arose primarily from pressing questions derived from work with living populations” (2018:18). Miller goes on to say it would be incorrect to suggest we are “simply applied as opposed to theoretical or that these two stand in opposition” (2018:18). Rather, our approach reflects the fact that we are very much engaged with the “highly dynamic situation regarding Indigenous rights and their place in Canadian society. Especially over the last two decades First Nations have achieved a significant level of self-governance along with key legal victories concerning the Crown’s obligation to consult with them concerning economic development and the Crown’s fiduciary obligations” (Miller 2018:18).

The UBC School’s principle of engagement can be seen throughout and beyond the Department of Anthropology and across much of its history. Borden’s partnership with Musqueam, and specifically with Andrew Charles Sr., created a relationship that persists and was recognized in UBC’s Memorandum of Affiliation with the Musqueam Indian Band, on whose unceded territory UBC sites, in 2007. Department scholars have developed and maintained long-standing partnerships with communities (many Indigenous, but not all) around the word. This work strives for equitable and respectful rapport toward research that is empirically based, theoretically thoughtful, cognizant of historical and structural asymmetries, and directed toward meaningful and mutually beneficial goals. Work of this order facilitates, rather than impedes science by advancing our cumulative understanding of complex issues and assessing our vulnerabilities to ethnocentric assumptions and bias.

This is an excerpt from “I was surprised:” The UBC School and Hearsay. A Reply to David Henige. C. Menzies and A. Martindale. Journal of Northwest Anthropology. Vol. 53.

The Journal of Northwest Anthropology invites the readers of this blog to read the original opinion piece by David Henige and the full response from Andrew Martindale and myself, which can be found at www.northwestanthropology.com/dashboard. Use the password: JONA2019 [after March 31, 2019].