Quiz Writing [updated]

Here’s the deal -it takes work to answer a quiz or an exam. However, it’s not simply how much time you put in, it’s really about learning how to study smart. Sometimes we can find ourselves spending lots and lots of time preparing for something but not get anything accomplished. To be able to manage a full load of university courses, a life beyond class, maybe a job, etc, means being able to studying effectively and not waste your time.

Smart Study means listening to what is said in class (remember the blog on ‘what’s the prof want anyway?). The lecture gives you the ROAD MAP to a satisfactory grade (for the mark inclined -that’s a C+/B-). Read more, participate in tutorial discussions, ask questions in lecture, talk to your prof and TAs (we can be found fairly easily), generate questions as you read. If you engage in smart study you will do okay.

The Quiz. the quizzes will draw from lecture and readings.

Format: Each quiz will have two basic sections. The first will involve short, fill in the blank and/or matching type questions. The second will involve answering a number of paragraph type questions. For this section there will typically be a set of three or four possible questions from which students will select two or three to answer in the space provided.

One of the hard things about a first time experience with university examination is it is unlike highschool exams. The structure and content of the test isn’t laid out for you ; you won’t be told what exactly is on the quiz or exam. You will have to work at it, but the signs are fairly clear.

- Course outlines have headings and assigned readings under those headings. Read the heading. For our first unit the main heading is: “What is Anthropology.” This should give a student a really clear indicator of the primary learning goal of the unit -that is, you are learning about what makes something anthropology. In class we have been talking about how it is that anthropologists do what ever it is we do. It would seem that this involves research (called fieldwork in anthropology), key concepts (i.e. conceptual tools used in doing anthropology), and some basic understanding that there are several types of anthropology.

- Lectures have structure -take notes following the lecture structure. Sometimes it might seem hard to figure out what to take notes on -everything? or, just the important things? (but then ‘what is important’?). When a prof uses powerpoint or overheads it makes your job as a student a little bit easier. Normally we (ie profs) select key words or phrases that highlight what we have decided are the most important of critical issues. Thus, your job of figuring out what is ‘important’ is made easier.

- Now put readings and lectures together. Compare your notes of lecture with your notes from the readings. If you are a habitual highlighter -consider locking your highlight pen away and opening up a notebook in which you write into it the key ideas from the things you read; don’t waste your time highlighting everything in the assigned readings. By the time you’ve finished highlighting your book will likely look like a rainbow.

- Finally, if you haven’t been reading along as per the course outline you will find it harder to speed read and catch the wave in time for your quiz. Of course, there are those among us who can read the textbook the night before and do okay (or even great). But for the majority of us doing well on a quiz, a term paper, or an exam is the product of smart study and hard work.

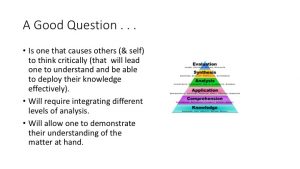

More info on exams and exam writing can be found under the ‘good question’ post.

Edited and updated. Originally published October, 2010.