A few days ago Fiona wrote two posts about Twitter, tweets, and Twitter essays: in the first, she discusses Jeet Heer, who numbers tweets to structure them together into an essay; in the second, she talks about how a person ought to read tweets. In particular, Steven Salaita had an offer for a tenure position withdrawn over a tweet which seemed, on its own, to be incendiary:

Zionists: transforming “anti-semitism” from something horrible into something honorable since 1948.

Salaita claims that, in the context of his overall Twitter career, this tweet isn’t as bad as it looks; it means something different when it is part of a whole. Fiona therefore asks the following question:

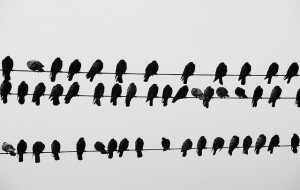

How far forward or back in someone’s tweet corpus must we look to be satisfied we have enough context? What are our responsibilities as readers? What are the boundaries of a twitter storm? What is the flock that holds our unmarked sheep?

I want to approach this question—approach, not answer—but first we need to get into some literary theory.