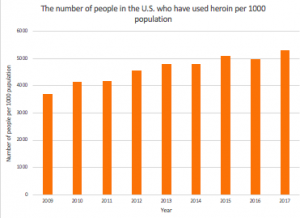

Since its development in 1962, ketamine has been used primarily as an anesthetic for veterinary procedures. In recent years, however, research investigating its use has extended to psychiatry, with evidence supporting ketamine as a viable treatment for Major Depressive Disorder, colloquially known as depression.

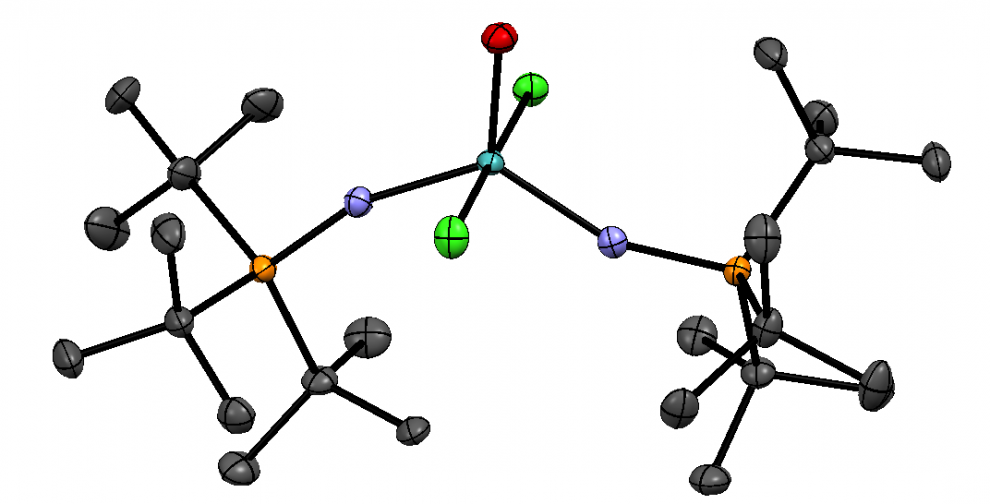

Figure 1. Chemical structure of Ketamine

The most commonly used antidepressant drugs are tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI). Upon daily administration, these drugs relieve depression, but only after approximately 3- 6 weeks. Moreover, for those with treatment-resistant depression (TRD), SSRIs prove to be of little benefit. Remarkably, current studies suggest that ketamine improves symptoms within 30 minutes, with therapeutic effects for even TRD patients.

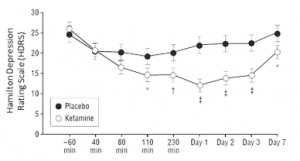

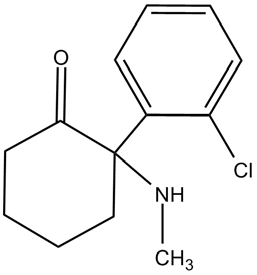

An article published in JAMA elucidates the potential of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) ketamine for the treatment of TRD: in a preliminary study involving eight subjects with depression, Zarate et al determined that a single dose of NMDA ketamine resulted in a rapid but short-lived antidepressant effect. In a subsequent double-blind randomized clinical trial, subjects received intravenous infusions of ketamine hydrochloride or midazolam as placebo. The participants used the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) to measure the changes in drug efficiency. As seen in the linear mixed model, in Figure 2, the difference between ketamine and placebo treatment over 9 points from baseline to 7 days were examined with standard error. Within 110 minutes after the injections, participants receiving ketamine showed significant improvement in depression compared to subjects receiving placebo (with P<0.05).

Figure 2. Changes in the 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS)

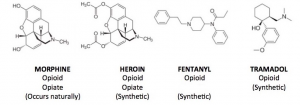

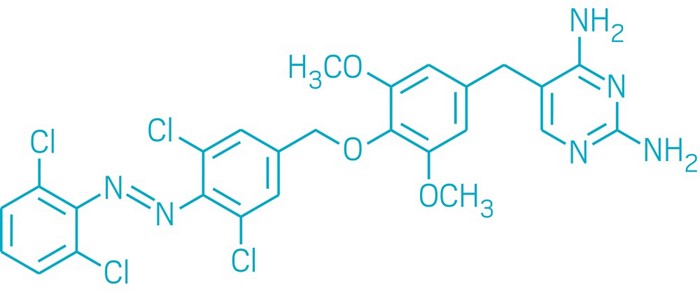

The implications from this study and the many other breakthrough studies have not gone unnoticed. The development of chemical variations of ketamine has shown that the drug is a powerful tool that can allow people to live life to the fullest potential. In fact, on March 5th, 2019, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Esketamine, a nasal spray formulation derived from ketamine, for TRD. Targeting the brain’s glutamate pathway, Esketamine is the first drug in thirty years to be approved with a new mechanism of action for treating depression. Of course, the FDA approval of Esketamine does not negate the lingering caveats and concerns relating to its abuse. Nonetheless, even as studies continue to investigate Esketamine’s adverse effects, many physicians remain optimistic that it may become “the biggest breakthrough in depression treatment since Prozac.”

Figure 3. Esketamine, which will be marketed under the trade name, Sparavato

In the following video, Dr. J. John Mann at Columbia University highlights the importance of the approval of Esketamine and the potential risks involved.

-Brina