Photoswitchable drugs: the light at the end of the tunnel?

For many developed nations, cancer has become the leading cause of death. Regrettably, the current state of cancer treatment still rests heavily on chemotherapy and its toxic side effects. More than ever, our efforts to further develop targeted cancer therapeutics are of paramount importance.

In more recent years, chemists have begun designing light-activated molecules that can be activated upon contact with its target tumor cell and deactivated following cell death. That said, photoswitchable drugs are not a novel concept; in fact, scientists have been considering synthetic light-switching molecules as promising treatments for blindness, diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, and antibiotic resistance, to name a few.

Previously, treatments for skin cancer relied on photodynamic therapy (PDT), a process during which patients receive dyes that convert oxygen molecules into their toxic singlet forms capable of killing diseased cells upon activation by light. Given its requirement of oxygen in the body’s tissues, the applicability and potency of PDT are limited by hypoxic tumor environments in which cancerous cells survive without oxygen.

Comparison of (a) classic chemotherapy and (b,c) photopharmacological chemotherapy DOI:10.1002/chem.201502809

Dr. Phoebe Glazer at the University of Kentucky believes that photoswitchable therapies offer a possible strategy for overcoming this restriction. By deriving energy from photons to induce a chemical reaction, photoswitchable therapies enable molecular changes conducive to the recognition and destruction of diseased cells. This approach, unlike current chemotherapy treatments, is capable of killing tumors and saving healthy tissue with specificity, thereby maximizing possible dosage and minimizing dangerous side effects.

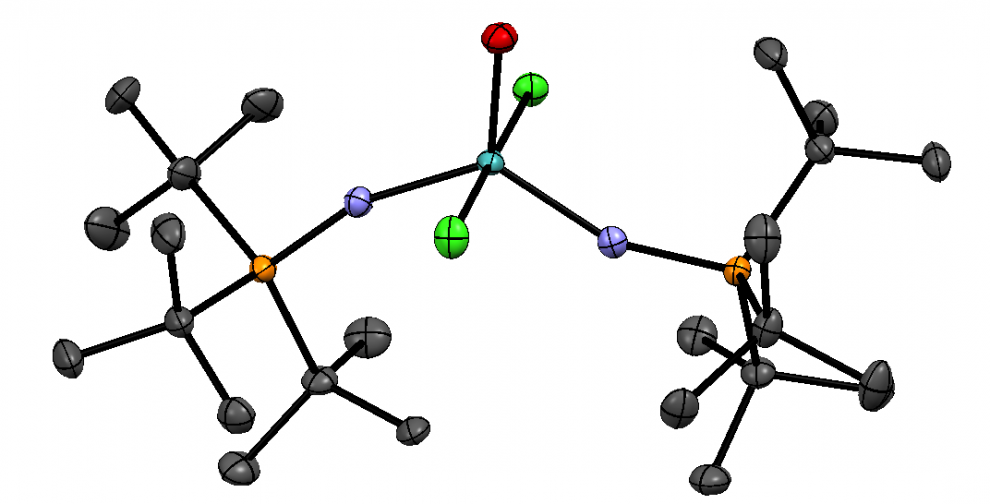

Glazer promotes photoactivated chemotherapy drugs that can function as both PDT sensitizers and one-way photoswitches. Using a ruthenium (II) polypyridyl complex, Glazer irreversibly ejected a methylated ligand, and with light, induced the complex to bind to DNA for ultimate cell damage. By modifying the drugs’ ligands, Glazer tuned the molecules’ solubility and the light absorbance wavelength.

ruthenium(II) polypyridyl complexes DOI: 10.1021/ja3009677

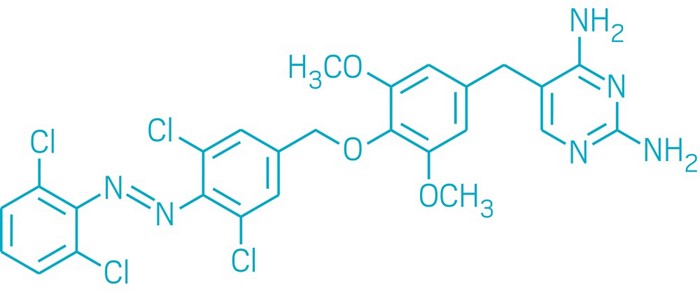

Many chemists, including Dr. Wiktor Szymanski at University Medical Center Groningen, are experimenting with molecules that can be switched on and off by light. Once developed, the resulting drugs can be turned on by contact with a targeted cancer cell and turned off after cell destruction. By adding the photoswitchable group, azobenzene, and using UV light to convert the molecule’s configuration, Szymanski produced photoswitchable molecules.

Photoswitchable molecule developed by Szymanski, Feringa, et al. DOI: 10.1021/jacs.7b09281

Of course, a handful of concerns must be addressed before such “on and off” drugs can become reality. Scientists need to ensure that their switches can work at tolerable wavelengths, specifically ones that can pass through tissue without causing damage. Dr. Achilefu at the Washington University School of Medicine has developed a method called stimulated intercellular light therapy where light is captured by the molecules that target tumor cells. This light has been designed to reach tumor cells beneath the surface of the body (explained in the video below).

Because of the extreme difficulties and complications related to the synthesis of small molecular drugs, many chemists are skeptical about the approval process of photoswitchable drugs. However, with more research and development, I believe that photoswitchable drugs offer a viable pathway for the future of cancer treatment.

-Brina Kim