More than 100 years ago a Dutch scientist named Heike Kamerlingh Onnes at Leiden University discovered a phenomenon in mercury know as superconductivity. When cooled to -269°C the mercury exhibited zero electrical resistance unlike conventional materials that release heat when transporting electricity.

Why is this important if it requires such a cold temperature? Over the past 100 years scientist and engineers have incorporated this phenomenon into our daily lives. This allowed for dramatic advancements in medicine such as the development of the MRI. Our power grid also takes advantage of this weird property. However, only select materials exhibit superconductivity when cooled below a temperature referred to as the critical temperature.

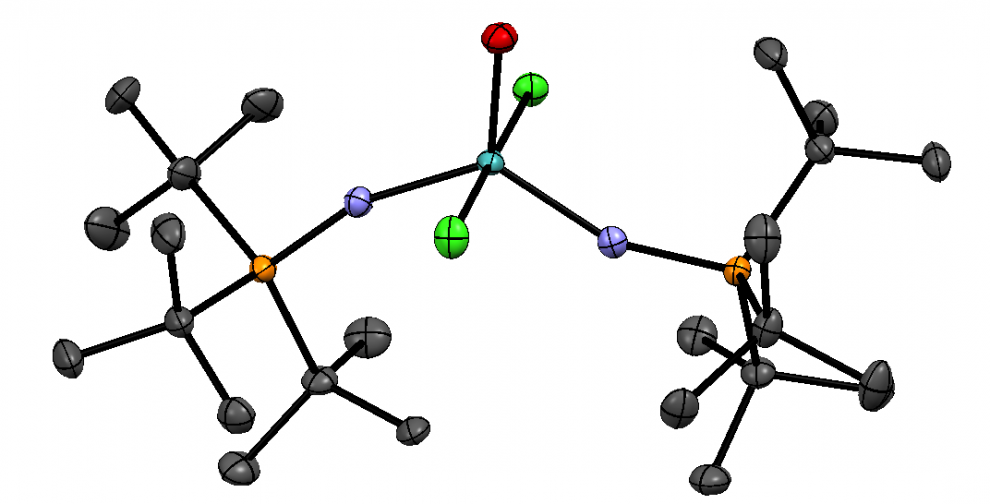

An example of a superconducting radio frequency cavity on display at Fermilab made of Niobium, a common metal in superconductivity applications. Source: Wikimedia Commons

In 1987 the technology was revolutionized when a material called yttrium barium cuprate was found to exhibit superconductivity below -181°C. This temperature is easily reached with liquid nitrogen, a widely accessible coolant. This marvelous material has found itself applied at the Large Hadron Collider in Geneva and most hospitals. While materials with higher critical temperatures have been slowly discovered, recent advancements have been shattering the records.

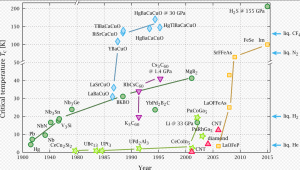

Timeline of Superconductive Materials

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Among these superconductors are a class which only exist at extremely high pressures. The smelly gas that comes from volcanos and is reminiscent of rotten eggs, Hydrogen sulfide (H2S), is one of these. When cooled to -70°C at 1.5 million atmospheres, hydrogen sulfide exhibits an exotic form of high pressure superconductivity. This discovery in 2015 by Mikhail Eremets and Alexander Drozdov at the Max Plank Institute for Chemistry in Mainz, Germany toppled previous records by 39°C, a significant breakthrough in the search for room temperature superconducting materials. Mikhail Eremets said: “Our research into hydrogen sulfide has however shown that many hydrogen-rich materials can have a high transition temperature.”

This has held true with a recently published paper by the same team in December of 2018. Lanthanum superhydride (LaH10) was found to be superconducting at -23°C, however it was at similar pressures to the previous discovery. This value was found to be even higher at -13°C when pressurized up to 2 million atmospheres as published by scientist at George Washington University in January of 2018. Maddury Somayazuli, an associate professor at The George Washington School of Engineering and Applied Science said: “Room temperature superconductivity has been the proverbial ‘holy grail’ waiting to be found, and achieving it-albeit at 2 million atmospheres-is a paradigm-changing moment in the history of science.” Future experiments are expected to provide more breakthroughs in the field.

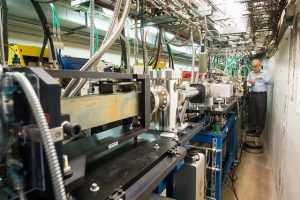

An engineer at the Advanced Photon Source, part of Argonne National Laboratory where GW University experiments were preformed. Source: Advanced Photon Source Flicker (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

While high pressure superconductors lack application, understanding this property may allow for the development of new materials. With continued research and the recent breakthroughs, the phenomenon of superconductivity may further be propelled into future technology that will have a significant impact on our quality of life.

-Jonah

References:

1.Drozdov et al, “Superconductivity at 250K in Lanthanum Hydride Under High Pressure,” arXiv:1812.0156 [cond-mat], Dec. 2018. 2.Somayazuli et al. (2019). Evidence for Superconductivity above 260K in Lanthanum Superhydride at Megabar Pressures. Physics Review Letters, (122), 027001-6. 3.Researchers Discover New Evidence of Superconductivity at Near Room Temperature. (2019, January 15). Phys.org. Retrieved from https://phys.org/news/2019-01-evidence-superconductivity-room-temperature.html 4.Superconductivity: No Resistance at Record Temperatures. (2015, August 18). Max-Planck-Gesellschaft. Retriever from https://www.mpg.de/9366213/superconductivity-hydrogen-sulfide 5.Eck, J. (2018). The History of Superconductors. Retrieved from http://www.superconductors.org/History.htm