A group of researchers at the University of British Columbia recently found that sea lampreys, an ancient species of jawless fish, appear to respond to stress much more differently than scientists originally thought.

Many species of lampreys are parasitic. Sea lampreys lack jaws and have suction-cup-like mouths that are lined with teeth, which they use to latch onto fish and suck their blood.

Source: Shutterstock.

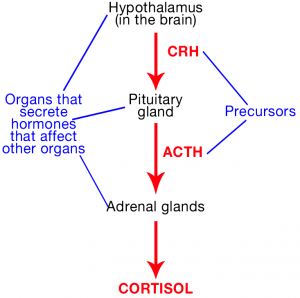

The paper, which was published in General and Comparative Endocrinology in 2013, detailed a two-year-long experiment that culminated in some unexpected results. The researchers were attempting to determine whether previous assumptions about stress regulation in lampreys were true. By injecting lampreys with certain chemicals, called hormones, that are turned into “stress hormones” in other vertebrates, the researchers checked the lampreys’ blood levels for these “precursors” and for the stress hormone, cortisol, to see whether lampreys also turned each of these precursors into cortisol.

Click image to enlarge.

Simplified diagram of the classic stress response seen in many vertebrates.

Source: Jenny Labrie.

For years scientists had assumed that lampreys, like other fish, had a stress response that involved the same three types of hormones – corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), adrenocorticotropin (ACTH), and cortisol – that are seen in humans and other animals. These three hormones and their involvement in the stress pathway is discussed in the video below, as well as what is already thought to be true about the evolution of the stress pathway.

The researchers found that, similar to other animals and to fish, lampreys do respond to CRH with increased levels of stress. CRH is a precursor to stress hormones in different species; in humans it is cortisol, which has been popularised over the past few decades as the concept of “stress” has received increasing amounts of attention – both from academia and the popular media. The lampreys injected with CRH displayed increases in their own type of cortisol, indicating that they were indeed experiencing stress in response, just as humans would.

Unexpectedly, the lampreys did not respond to several types of ACTH that they were injected with. In both humans and other fish, ACTH is the hormone that is released in response to CRH and eventually stimulates cortisol release, which causes classic signs of an activated stress response (e.g., increased heart rate).

What does this mean? Well, yes, scientists were once again mistaken; lampreys are not just like every other fish. But why should this matter? Who cares about this 505-million-year-old fish?

Click image to enlarge.

Source: Wikimedia Commons. Originally illustrated by Ernst Haeckel, and published in ‘Generelle Morphologie der Organismen’ (1866).

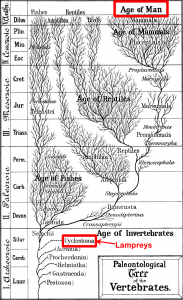

As it turns out, we all should. Contrary to popular opinion, scientists don’t know everything there is to know about human evolution, but we can fill in some of our knowledge gaps by studying lampreys. A better understanding of stress regulation in lampreys helps us better understand how this system has evolved since the time of these early vertebrates. Humans diverged from lampreys 500 million years ago, and we are related to them – as uncomfortable a thought that may be for some people. This link means that lampreys may be key to understanding the origins of biology in many higher vertebrates – including humans!

Perhaps for this reason alone it is worthwhile to strive to conserve lamprey species, and this research does also have implications for protection of certain lampreys, as discussed in the podcast below.

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

Some have hailed the sea lamprey as an up-and-coming “evolutionary developmental model of choice.” Clearly, even blood-sucking parasites have their place in nature’s plan.

Text, video, and podcast by Jenny Labrie, Kelly Liu, Rubina Lo, and Kathy Tran.

—

References

Close, D.A.; Yun, S-S.; Roberts, B.W.; Didier, W.; Rai, S.; Johnson, N.S.; and Libants, S. (2013). Regulation of a putative corticosteroid, 17,21-dihydroxypregn-4-ene,3,20-one, in sea lamprey, Petromyzon marinus. General and Comparative Endocrinology, 196: 17-25.

Kimura, M. (1969). The rate of molecular evolution considered from the standpoint of population genetics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 63(4): 1181-1188.

Nikitina, N.; Bronner-Fraser, M.; and Sauka-Spengler, T. (2009). The sea lamprey Petromyzon marinas: a model for evolutionary and developmental biology. In K. Behringer (Ed.), Emerging model organisms: a laboratory manual (pp. 405-421). Cold Spring Harbor, NY: CSHL Press.

—

Further reading

The sea lamprey and its cousin the Pacific lamprey

—

Lampreys in the news

Scientists find genes linked to human neurological disorders in sea lamprey genome

Sea lampreys provide a unique solution to gene regulation

Lamprey research sheds light on nerve regeneration following spinal cord injury