2095 has come. Earth houses more than 10 billion inhabitants. The air can no longer nourish us like before as plants fail to catch up with carbon emissions. While new species have arisen, even more have fallen. People’s diets consist of a few staple crops, nothing like the colorful selection from the supermarkets decades ago. What caused this to happen?

Is this our future? Wall-E next to a pile of trash, from the 2008 Disney Pixar film WALL-E. Image from Danielle Jabams on WordPress.

While this may seem like the opening of an apocalyptic film featuring Matthew McConaughey and Anne Hathaway, the possibility of this happening does not come as a surprise and, in fact, it has happened before.

Plants make the foundation of our food chain, so a threat to their livelihood equals to a threat to us. Disease, drought, flood, soil pH changes, amount of sunlight, and temperature affect the plant’s survival and growth. Especially with extreme climate changes, farming becomes more difficult.

Dr. Kantar proposes a preventative solution to this oncoming problem: crop wild relatives. But what do these crop wild relatives (CWRs) represent and how will they help?

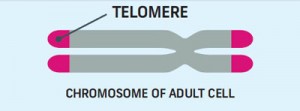

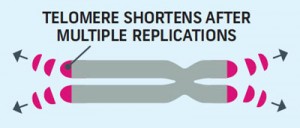

From the name, CWRs describe wild plants genetically related to our domestic crops such as corn, wheat, or barley. “Genetically related” means the wild plants can produce fertile offspring when crossed with domesticated plants. In other words, the crop wild relatives belong to the same species as domestic crops, but grow in the wild. However, crop domestication actually affects the plant’s genetic diversity. The following video explains the importance of CWR as a source of genetic variation.

Dr. Michael Kantar, our UBC research correspondent, presents the proper utilization of CWR using public databases. Extreme climate changes, such as the drought in California, makes planting very difficult, but Dr. Kantar’s research provides a solution to help our domesticates adapt better to the ever-changing climate. With his method, any breeder, professional or otherwise, can improve their crops by crossing the domestic crop with the CWR.

Using CWRs might sound quite similar to genetic modification (GM) technology. However, the difference lies in the respective products’ genetics. As Dr. Kantar puts it, genetically modified organisms (GMOs) have “…gene[s] that [don’t] exist within the organism.” With the CWR method, the product contains “…no foreign DNA, it’s all native DNA.” Those concerned with how “natural” GM technology may be more accepting of CWRs and see them as a more “organic” process. The genetic cross in CWR could happen in nature given plants in close enough proximity.

Dr. Kantar’s CWR method simply speeds up this natural process. Using sunflowers’ crop wild relatives as a model species, he claims that home gardeners or even undergraduate students (with enough dedication) can follow what he did to effectively produce a more viable plant. Imagine a basil plant that cannot be eaten by aphids, or a tomato plant that can grow indoors all year! The technology exists; we just need to go back to our roots.

There is hope! Wall-E has found a plant that has adapted to the environment, from WALL-E (2008). Image from Deja Reviewer on WordPress.

– Chelsea Cayabyab, Amir Jafarvand, Doris Stratoberdha, Trevor Tsang & Even Zheng