This is the second post in a new series from the course “Topics in the History of Education: Histories Confronting White Supremacy,” led by Professor Mona Gleason.

This course delves into colonialization, racism, and systemic oppression, exploring how historical understanding shapes our world today. In this series, students collaborated to craft blog posts where they explore themes related to course topics and share their insights with the larger EDST audience.

Co-authored by Lidia Jendzjowsky (LJ) and Serena Pattar (SP), this post explores how pervasive tropes in social studies textbooks shape the teaching of Canadian history. They discuss how these tropes perpetuate white supremacy and colonialist narratives, while also highlighting recent curriculum shifts towards more inclusive perspectives, encouraging critical thinking, and addressing the impact of colonization on Indigenous and marginalized communities.

Co-authored by Lidia Jendzjowsky (LJ) and Serena Pattar (SP), this post explores how pervasive tropes in social studies textbooks shape the teaching of Canadian history. They discuss how these tropes perpetuate white supremacy and colonialist narratives, while also highlighting recent curriculum shifts towards more inclusive perspectives, encouraging critical thinking, and addressing the impact of colonization on Indigenous and marginalized communities.

There is much to be gained from examining the role of pervasive tropes in how Canadian history is taught, conceptualized, and represented in popular media and official social studies textbooks.

The idea of “tropes,” especially in social studies textbooks, has been used and circulated in Canadian history– specifically in the images and stories of “the settling of the west.” In the context of the teaching of history throughout the twentieth century in the K-12 system, clichés and stereotypes have been prevalent in the representation of Indigenous peoples and cultures in Canada. Not only were Indigenous peoples described in a certain way, their perspectives (and others) were silenced by the re-telling of events through the eyes of the settlers.

The (re-)presentation of tropes as a way of teaching history has also included key Canadian tropes. In western Canada, images of “settling the west,” “empty landscape,” and “developing the land” were key tropes. These tropes evoked images of a land that did not have any people or communities already living on it and that it was not until the arrival of the settlers that “wilderness” was “civilized.”

This description of early Canadian history, consciously or unconsciously, included the message that the Indigenous peoples were non-existent and did not have to be considered a part of Canada’s early history.

In the last thirty years of teaching of history, for example, we remember Heritage Minutes, which were vignettes on television that celebrated aspects of Canadian culture. I (LJ) certainly remember these short films as a way of learning about Canadian history as static moments frozen in time.

But Heritage Moments only celebrated Canadian history in a positive light that should be celebrated. They did not open up discussion or attempt to unpack the difficult events that are also part of Canadian history.

However, recent shifts in how history is presented in social studies curriculums and textbooks can counter these pervasive tropes. In my (LJ) opinion, this shift can be attributed, in part, to the advancement of the United Nations Declaration on Indigenous Peoples and the Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission focusing on Residential Schools at the forefront. There is a distinct trope of a “frozen-in-time” Indigenous peoples. This trope highlights the need for a political and social shift that attempts to address and understand a wider range of events and people that make up Canadian history.

Do Social Studies Textbooks Perpetuate White Supremacy?

The inclusion of more diverse perspectives in British Columbia’s Social Studies curriculum is evidence that there is more of a conscientious effort to combat the white supremacist, single-narrative history that has been taught for so long. As is the new “Indigenous Graduation Requirement,” where all students must take an Indigenous-focused course.

As a social studies educator (SP), working with the new curriculum is not always easy when the materials—mainly textbooks—have not been updated to reflect this new mindset. Many textbooks showcase a settler thought process towards Indigenous groups, and often gloss over the systemic laws and barriers placed upon groups by predominantly white-Eurocentric governments. In doing so the rich history of Indigenous and other minority groups is sidelined and perpetuates a continued historical imbalance of whose history is allowed to be shared and whose history “counts.”

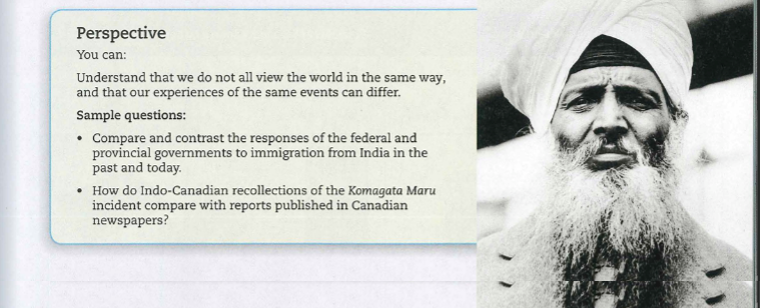

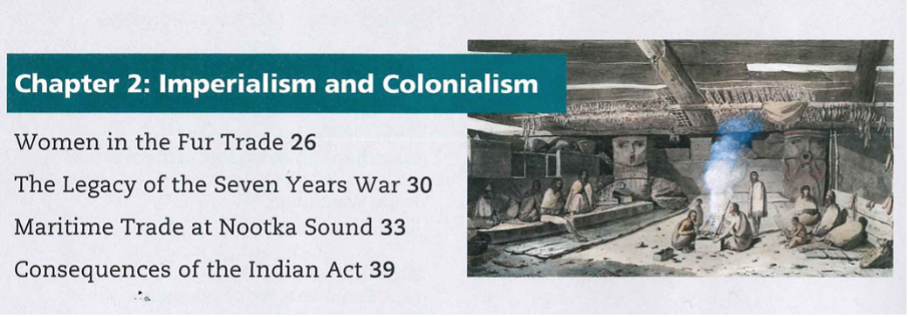

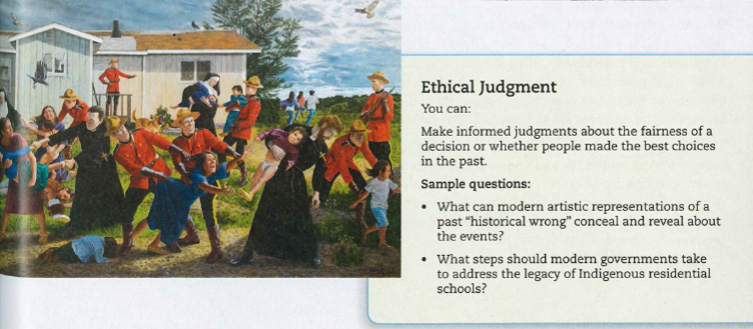

However, with updated textbooks, specifically Thinking it Through: A Social Studies Sourcebook by Glen Thielmann et al. (2018), the promise of a more inclusive narrative that centres both marginalized and Indigenous histories is evident. By offering a more inclusive narrative, the Sourcebook actively challenges the foundations of white supremacy in historical education by exposing students to a broader range of perspectives, fostering a nuanced understanding of the past that goes beyond the typical Eurocentric views and voices that have dominated previous textbooks. This approach not only aids in dismantling stereotypes but also cultivates respect and empathy for marginalized and Indigenous groups, diverse cultures, and communities that have shaped Canada’s history.

The textbook emphasizes critical thinking and analysis rather than presenting history as a static and absolute narrative. This shift encourages students to question, evaluate, and interpret historical events and perspectives, while reflecting on power dynamics, oppression, and resistance throughout Canadian history. The use of historical documents—photos, letters, legal documents—are employed to showcase other perspectives and encourage students to look beyond what is on the page and consider Canadian society at that time.

The updated text also addresses the impact of colonization and its enduring consequences, providing a more comprehensive examination of the historical injustices faced by Indigenous peoples, immigrant communities, and other marginalized groups.

It should be mentioned, however, that although the Sourcebook is available, educators may choose not to utilize it. As Jennifer Tupper has warned, educators, too, can become stuck in the “settler imaginary” and “settler historical consciousness” that downplays complicity in the ongoing harms of colonization and instead replay tropes associated with the so-called “true” Canadian history (Tupper, 2018). Teachers may not be ready to face their own complicity in settler colonial history.

When I (SP) was in school, these historical injustices were not acknowledged; as a South Asian Canadian, I did not feel represented in what created the rich tapestry of Canadian history. By acknowledging and exploring the consequences of colonialism, the Sourcebook allows for a more honest and transparent discussion about the legacy of systemic racism and inequality in Canada.

References:

- King, Thomas. “Chapter 3: Too Heavy to Lift,” in The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America, 53–75 (Random House, New York: 2013).

- Thielmann. Glen, et al. Thinking it Through: A Social Studies Sourcebook (Pearson, Toronto, CA: 2018).

- Tupper, Jennifer. “Cracks in the Foundation: (Re)Storying Settler Colonialism,” in Oral History, Education, and Justice: Possibilities and Limitations for Redress and Reconciliation, 88–104, eds. Kristina Llewellyn and Nicholas Ng-A-Fook (Routledge, New York: 2020).

Share

Share