Introduction

An April 2023 article in the Engineers and Geoscientists BC magazine “Innovation” is titled “Geoscientists: Are there enough to fill demand?”** It uses annual enrollments in geoscience degree programs and GIT or Geoscientists In Training statistics, with quotes from professionals and academics, to suggest that demand for geoscience expertise in BC currently outstrips supply. This apparent shortage of geoscientists and workers seems wide spread; see also Keane & Wilson, 2018, Keane, Gonzales & Robinson, 2021, Legault & Howe. 2021, Summa et al., 2017 (references).

Is high demand for STEM graduates a myth?

It generally seems that more students graduate with a BSc in STEM disciplines than there are positions in STEM occupations; 36.6% of all US workers with a BSc completed their degree in a STEM discipline while 14.4% of all US workers with a BSc degree are working in a STEM occupation (US Census Bureau, 2021). Data presented by the US National Science Board, 2022 are similar. The point was also discussed in the press over 10yrs ago – Yglesias, 2014. There are nuances to these sorts of data. For example medical disciplines are sometimes consider as STEM professions and sometimes not.

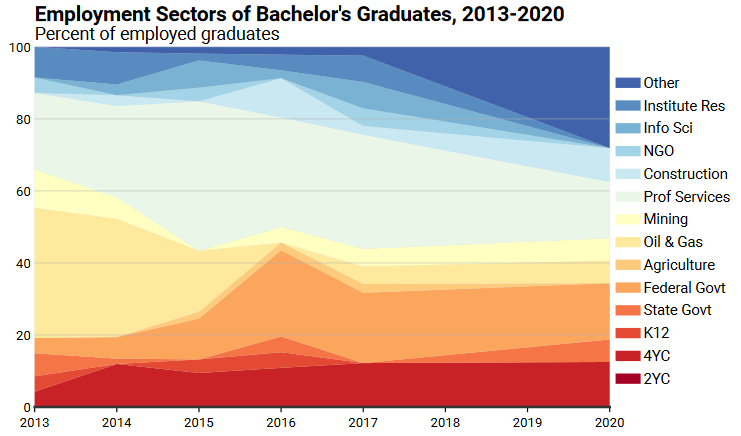

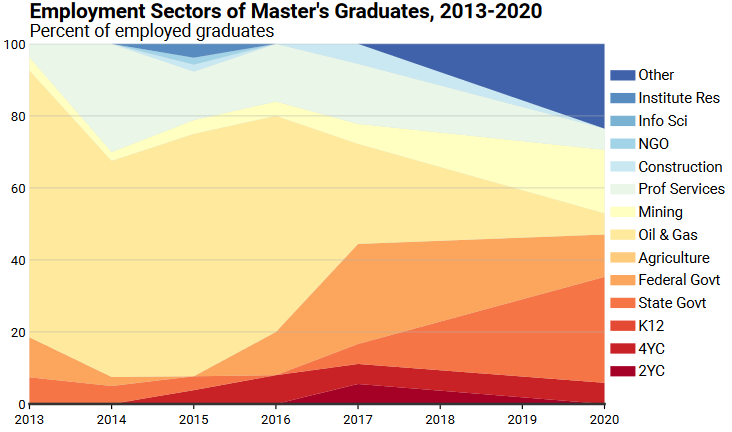

Further insights about current and recent shifts in BSc and MSc level hiring for 14 different employment sectors are illustrated as 7-year trends reproduced below. Sources for keeping up to date with the state of STEM workforce demand and education include:

- US Census Bureau. “From College to Jobs: Pathways in STEM.” Census.gov, May 2021. https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/from-college-to-jobs-stem.html.

- National Science Board. “The State of U.S. Science and Engineering 2022 | NSF – National Science Foundation,” 2022. https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsb20221/u-s-and-global-stem-education-and-labor-force.

- IEEE Future of Workforce report by IEEE Industry Engagement Committee, via IEEE at https://www.computer.org/resources/future-of-workforce-report, and summarized For Forbes by T. Coughlin.

General demand for geoscience

Based on a broad analysis of over 3600 geoscience job advertisements (Shafer 2023), there currently seems a reduced demand in geoscience occupations for BSc graduates with significant numerical and data science capabilities.

On the other hand, expectations expressed by academic and industry participants in an NSF-funded project that studied the future of geoscience education suggest a growing need for quantitatively capable workers across the geosciences (Mosher and Keane, 2021). Consistent with this general perspective are statements specific to the geophysics resource exploration industry, such as “…the metals for the future are becoming harder to find, and we need to find and extract them with less impact. These factors demonstrate the growing need and bright future for geophysics in the mining industry”, quoted from Legault & Howe, 2021. The article mentioned above in the introduction paints a similarly optimistic future for minerals sector geoscientists more generally. Global expectations are also favorable:

- Growth in exploration spending and trickle down impacts on demand for geoscience expertise. “Canada’s exploration budgets rose 62%, or $799 million, year over year to $2.09 billion, a nine-year high.” quote from pg 13 of World Exploration Trends 2022, S&P Global Market Intelligence.

- “Global exploration budgets rose 16% in 2022, following a strong 34% rebound in 2021. After budgets fell 10% year over year to $8.35 billion in 2020 due to the COVID-19 shock, nonferrous global exploration budgets hit a nine-year high of $13.01 billion in 2022. The increase was driven by escalating interest in the global energy transition as part of global decarbonization efforts and by the ongoing pandemic recovery, and was supported by strong metals prices and healthy financing conditions. How would uncertainties in the global economy and opening “f China’s economy shape the exploration sector in 2023? Download our report to learn more“. From S&P Global Market’s World Exploration Trends, 2023.

- Geophysics community in BC and Canada: Based on two years of volunteering on the Board of Directors of both the BC Geophysical Society (as scholarship coordinator) and the KEGS Foundation, the applied geophysics community in Canada continues to be vibrant, and is optimistic about the future of the geophysics industry. As always, the number of new hires each year remains small, but their contributions locally, across Canada and around the world are critical in the resources, energy and geotechnical sectors. Canada has a history and reputation of innovation and excellence in geophysics, and this can only continue if the principal research institutions continue to produce graduates with the diverse capabilities unique to applied geophysics.

- The demand for geophysical expertise continues to diversify is illustrated by the newly published textbook “Engineering Geophysics”, 2023, edited By Anna Bondo Medhus, Lone Klinkby. It includes 12 chapters of explanations about how the range of methods can be applied in geotechnical settings, but more impressively, there are 48 different case histories presented, illustrating a huge range of applications that contribute unique information to important societal challenges.

Of course these minerals and geotechnical sector perspectives may not say much about demand for BSc graduates from other disciplines such as atmospheric sciences or physical oceanography. However, growth in resource sectors includes growth in – or perhaps more correctly changes to – the energy sectors and needs for quantitatively capable professionals with a broad demand for professionals capable of solving quantitative problems involving the Earth and its atmosphere, its oceans and its environments.

The AGI’s Status of Recent Geoscience Graduates, 2021 provides many details about enrollments, demographics, curriculum, skills and employment of geoscientists. The 7-yr trends in 14 employment sectors for BSc and MSc graduates are particularly interesting (section 4.13 of their report). Figures from pages 68 and 69 reproduced here illustrate, although details should be explored in that status report.

For roughly annual updates on many facets of geoscience professions, the AGI’s Geoscience Currents resource collection provides snapshots of professionals, in-depth case studies of how geoscience is applied, factsheets with rigorous introductions to a range of geoscience topics, workforce trends, and career paths; well worth exploring periodically.

Arguments can be made regarding the importance to society of more visible, accessible and rigorous geoscience educational occupations, including increasing quantitative components across the spectrum of geoscience. Chapter 1, “A call to action”, in Mosher and Keen, 2021, includes 11 “key outcomes” of the NSF-funded “Future of Undergraduate Geoscience Education” initiative, one of which is “Growing demand for geoscientists requires departments and programs to recruit, retain, and promote the success of undergraduate geoscience majors across a broad spectrum of society.”

Other timely sources of geoscience workforce analyses include:

- Shafer, et.al., 2022: “Analysis of Skills Sought by Employers of Bachelors-Level Geoscientists.”

- Are we teaching what students need? This was asked and analyzed by Viskupic et al., 2021, “Comparing Desired Workforce Skills and Reported Teaching Practices to Model Students’ Experiences in Undergraduate Geoscience Programs“.

- Four statements summarizing current (2020-2023) geoscience workforce context, from Viskupic and Egger, workshop 2023:

- “Bachelor-level geoscientists represent the majority of the current geoscience workforce (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022).”

- “Bachelor-level positions are forecast to increase by as much as 10% (NCSES, 2021).”

- “Geoscience must do better at attracting and supporting students because geoscience is currently one of the least diverse STEM fields (Bernard & Cooperdock, 2020; Gonzales & Keane, 2020)”

- “Students (and research-oriented faculty?) have little awareness of career opportunities, and of what skills and abilities are needed in the workforce (Viskupic et al., 2022)”

- AGU’s EOS topic “Education and careers“, including the annual Career Issue: see professional profiles (mostly scientists) in issues 2021, 2022, 2023.

Specifics regarding the “niche” that is QES

Several colleagues at peer institutions suggested that they anticipate continued migration away from QES programs by making comments like “other quantitative programs like engineering are more practical” or “quantitative students are turning to the information economy”. However, perhaps this “gloomy” perspective might serve as inspiration for creative adjustment to the way earth science disciplines are offered to prospective undergraduate students? Quantitative specialists in the geoscience professions may be a small proportion of the total, but all sub-disciplines are expected to become increasingly dependent upon skills related to data assessment, management & analysis, and numerical modelling of physical and chemical processes to help anticipate, plan, design, and manage society’s needs and impacts on the Earth. Three indicators that could be taken as incentive to reinvigorate quantitative BSc Earth Science degree programs are:

- Optimism for long-term growth and evolution in the resource and energy sectors, mentioned above.

- From Canada’s Budget 2023: one of three highlights is “growing a green economy”, for which eight priorities are listed: 1. Electrification, 2. Clean Energy, 3. Clean Manufacturing, 4. Emissions Reduction, 5. Critical Minerals, 6. Infrastructure, 7. Electric Vehicle & Batteries, 8. Major Projects. Items 1, 2, 5, 6 and 8 are all directly dependent upon quantitative Earth science expertise.

- “Future of Workforce” from the IEEE Computing Society’s Oct 2022 Report (51 slides) and Exec summary (4 slides – graphical and succinct). This is extensive, global, and compiled over 1.5 years. Download or see reaction at Forbes magazine (Coughlin, 2022). This does not target geosciences, but implications are relevant graduates who can aspire to careers in a wide spectrum of occupations that require capable quantitative and data science professionals.

It could be argued that B.Sc. degree programs are more about learning fundamentals and maturing as a young adult and less about “job training”. However, most students embark on degree programs in order to become employed in rewarding and meaningful occupations. In EOAS, only 18% of 85 surveyed students said they planned to pursue further education beyond their BSc; Jolly, 2020. Therefore, educational programs need to be agile and responsive to changes in the sectors that will hire graduating students. This is one of the arguments for diversifying the more traditional, “siloed” or constrained degree specializations. And “diversifying” is needed both in terms of disciplinary and interdisciplinary diversity and in terms of the human diversity of students and professionals. As mentioned above, and discussed in the Nature – Geoscience article (Bernard & Cooperdock, 2020), the geosciences generally are found to be one of the least diverse STEM fields. Oceanographers Johnson et al., 2016 discuss strategies for increasing diversity in ocean science workforce, thus “cultivating future global ocean science leaders who collaborate effectively to make discoveries, achieve solutions, and develop technologies“. EOAS could aspire to be a leader in establishing effective, diverse and rigorous undergraduate programs in quantitative Earth sciences.

Conclusion

Perhaps one implication of all this discussion is that quantitative Earth science qualifications may continue as a “niche” degree option, probably with potential for some growth, especially as students recognize the need for rigorous background prior to gaining additional, specialized qualification at the graduate levels. However, if quantitative degrees could involve a greater diversity of students (both in terms of demographics and disciplinary interests) there is reason to be optimistic that rigorous and relevant undergraduate degrees in quantitative Earth sciences that transcend traditional silos can attract sustainable numbers of students.

**Note

Much of this page refers to “geoscience” because extracting information restricted to quantitative geosciences seems difficult or impossible. However, some details from the geophysics community are provided.