Indian Residential Schools* began in the late 19th century as partnerships between the Canadian government and churches. The last school closed in 1996. For much of this history, Aboriginal children were forcibly removed from their families and often separated from them for years. Many did not survive: the mortality rate for children in some schools was in excess of 60% and surviving children often returned to their communities angry, alienated and unable to adapt to community life. Many had experienced severe physical, psychological, and sexual abuse and, with no parenting skills or experience of family life, transmitted those abusive behaviours to subsequent generations. The devastating legacy of the schools affects the lives of communities to this day and nearly every Aboriginal family in Canada has been affected.

On June 11, 2008, Prime Minister Stephen Harper apologized to the Aboriginal people of Canada in Parliament for the Residential Schools and the harms they inflicted. Few Canadians, however, are aware of this history or its lasting effects. This lack of knowledge is no accident: expressions of Aboriginal culture were banned by Canadian law from 1885-1951 and only recently has significant address of Aboriginal culture and history been included in school curriculum at any level. That silence has left us with no widely shared understanding of the circumstances that have shaped Aboriginal experience. We are unable to understand each other or begin to talk from a common understanding, yet the issues we must navigate are critical to our common future.

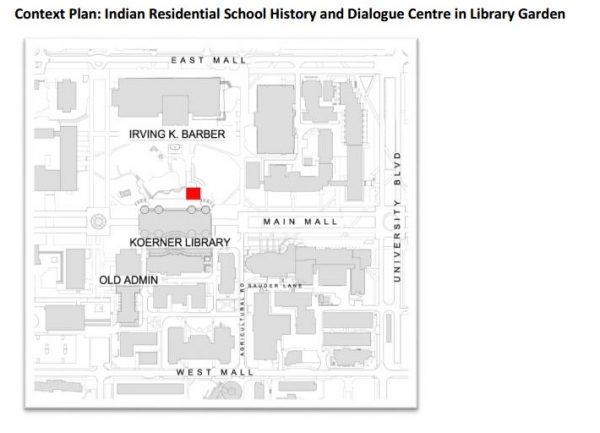

The UBC Board of Governor’s recently provided “Board 3” approvals for the Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre (the “Centre”) – construction is scheduled to begin this July. Located at the centre of campus, the Centre will provide an on-campus meeting place for community members and scholars and a powerful recognition of Aboriginal culture and history in the heart of campus; an area associated with knowledge, records and the preservation of memory. It will offer an unparalleled opportunity to inform and educate the campus community and visitors, providing a more complete understanding of Canada, its history and its future.

The proposed two level facility will have a gross area of approximately 6,700 ft2 comprised of a portion of existing basement space in Koerner Library and a new building component above next to the mid-level plaza

leading from Koerner Library to the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre. The Centre, which is targeted for completion in 2017, will build upon and complement the efforts and activities already in place in a way that is both unique and historically significant; another important way in which the university will fulfill its promise.

The Centre will serve as a venue for research, including Access to Truth and Reconciliation Commission records, and other records held locally at UBC, for survivors, families and communities. It will also serve as a platform for the development of advanced curriculum for programs at UBC and beyond, public engagement, and reconciliation. Founding the Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre is a major step in building a more civil Canadian society and just world. The Centre will empower Aboriginal communities and leadership, the university community, and a wider public to think and work together, in both physical and virtual spaces, and to continue the work begun by former students, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and others to better understand our shared history and the prospects for our future. The Centre is an opportunity to further address the wrongs identified in the TRC findings and acknowledged in federal, religious and institutional public apologies to Canada’s Aboriginal people. It is an opportunity to think together in a more informed way about decisions that will affect us all.

(Adapted from a May 10, 2016 report to the Board of Governors)

If you would like to learn more about residential schools, please consult the UBC Indigenous Foundations resource here.

*Though the term “Indian” is no longer a preferred term in referring to Canadian Aboriginal people, it is historically accurate in this context and used in both government and community documents and discussions to identify these schools and the policies surrounding them.