By David Cho

Dr. Lindsey Richardson’s course on Drugs and Society (SOCI 387) opened my eyes to what was happening in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Prior to taking the class, I knew of the Downtown Eastside in terms of stereotypes familiar to many. But I knew this was too simple to be the case. After Dr. Richardson’s course I began to understand the complexities and difficulties of the communities; reading countless papers about the experiences of people living in the Downtown Eastside provided me with a more multidimensional understanding of the area. Eager to learn more, I was told by a peer that the Urban Ethnographic Field School course did their ethnographies with organizations in the Downtown Eastside. I applied for the course right away.

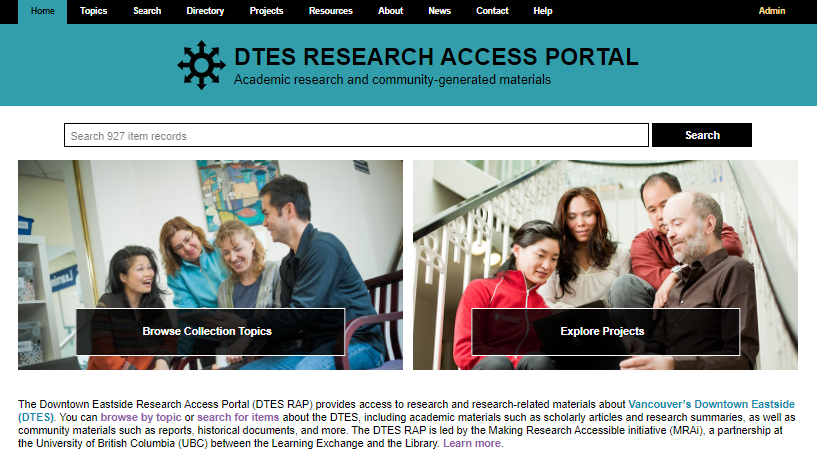

I was privileged to have the opportunity to work with Dr. Heather Holroyd and Matt Hume from the University of British Columbia Learning Exchange (UBC LE). My peers and I were tasked to collect items to add to the resource page on the Downtown Eastside Research Access Portal, a tool developed by the Making Research Accessible initiative. We searched the web to find resources that would aid researchers and prospective researchers in better understanding the communities they were researching. These resources were to provide insight on how the members of the communities wish to be approached and respectfully engaged with collaborators, especially by researchers and the media.

To be quite honest, at the beginning of this project, I thought that searching for these resources was not the best use of my time and that these resources were… trivial. But as I went through more and more resources made by the communities or co-authored by them, I realized the extent of disconnection between researchers and the communities and their members. Moreover, I learnt of the disconnect between me and the community members of the Downtown Eastside. I slowly began to understand why these resources were indeed beneficial, not just to the researchers, but to the communities as well. I came to understand that as better relationships are formed between researchers and the communities, better, more accurate, research will be produced, and better research will then lead to solutions and programs that actually benefit the communities of the Downtown Eastside. For the longest time, and for many still, the understanding was that research and solutions are created by researchers and policymakers. The communities and their members were excluded from the solution production process. Hopefully, through initiatives such as the Making Research Accessible initiative, researchers will become better equipped to understand and communicate with the communities to create research that makes a difference.

When I applied for the Urban Ethnographic Field School course, I never imagined that a pandemic would set in. As a result, I ended up doing virtual ethnography. I had a hunger to see the neighbourhood surrounding the UBC Learning Exchange, so I did what any student of the 21th century would do! I used Google Maps’ Street view. It was interesting how much one can learn and observe from just cruising along the street views of the Downtown Eastside. I saw elderly Chinese ladies on storefronts sitting and socializing, I saw small groups of street people congregating to have breakfast and socialize. I probably spent an accumulated 30 hours browsing through street view for the duration of my course, trying to collect data and uncover patterns in behaviours through these frozen images. As a student who is interested in psychoanalytic observation, it was challenging to investigate how organizations, their staff, and patrons actually behaved. To elaborate, websites, Facebook posts, photos, and videos are all curated to show the audience a sanitized version of what the organization wants them to see. On the other hand, behaviour and speech, no matter how curated, will have their slips, which can expose underlying beliefs, values, and goals. Fortunately, through attending the LE’s online tour of the UBC Farm, I was able to see some live interaction between the staff and patrons. The online farm tour felt awkward from a privileged 21st century university student. Much like my general experience with the UBC LE, it became obvious to me that this was not just a simple “farm tour” experience for patrons of the UBC LE. It was also a chance for patrons of the LE to socialize and to develop or draw on their digital literacy and navigation skills and so forth.

Many courses offered in universities don’t provide a lot of insights into life and society. The material tends to be heavily curated and sanitized for students. They are rarely given the opportunity to understand the lived experiences of the marginalized populations. The Urban Ethnographic Field School course and the UBC LE offered me this opportunity. I came to the realization that bridging and brokering units such as the UBC LE seem almost… necessary, in an institutional sense. Units like the LE offer students, academic and community members the opportunity to connect and learn from each other’s experiences. This experience opened my eyes, not just as a sociology student, but as a citizen, to look beyond and try to understand through dialogue and communication what the Downtown Eastside communities are trying to tell me, and other students and academics like me.