Everyday leadership: How podcasts have contributed to my career transition

My career interests have expanded and shifted over the past ~2 years and it has taken me until now to start becoming public about this. Writing this post is a small act of courage: I am claiming and making known my in-transition and growing professional identity.

This post outlines how a few podcasts have had a key role in shaping the direction of my career. I am writing this to highlight the importance of everyday leadership and lollipop moments–those moments when people show up, share their inspiration and have a profound effect on someone else, often without knowing that they’ve done so. I feel much gratitude for the work of every person and podcast mentioned here.

Everyday Leadership through Podcasts

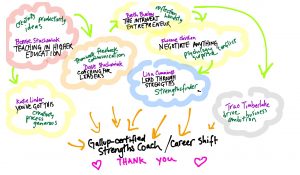

The visual below is my best attempt at demonstrating how the connections (note 1) were made and what theme//idea/guest in that particular podcast significantly contributed to my career transition. Under the visual is a brief textual description.

(Click on the image for a larger view)

[oh no, I cut off Dr. Tracy Timberlake’s name by accident!]

Text summary of the visual: It started with Bonni Stachowiak’s Teaching in Higher Education podcast. I don’t even recall how I discovered it but know that I was still fully immersed in my educational developer identity when I started listening. Bonni and her guests talked about teaching in higher education (surprise, surprise) and she also talked about this fine fellow Dave Stachowiak who has the Coaching for Leaders podcast. I had a hunch I might like it. I did, and do! On Coaching for Leaders, I was introduced to the Introvert Entrepreneur podcast by Beth Buelow. One day, Beth interviewed Kwame Christian who hosts the Negotiate Anything podcast. In one of his episodes, Kwame had a conversation with Lisa Cummings, of Lead Through Strengths, about ‘smart yesses and wise nos‘ and they talked about StrengthsFinder. I was intrigued and primed because I had taken the Clifton StrengthsFinder assessment in 2016 and had found it revelatory. I started to listen to Lisa’s podcast and, within a short time, began to seriously consider developing as a Gallup Strengths coach. Alongside the above podcasts, I was also hooked on Chris Guillebeau’s Side Hustle School and a regular listener to You’ve Got This, in which academic entrepreneur Katie Linder shared about her consulting ventures and inspirations.

The Transition and the Now

Approximately one year ago, I recognized the extent to which my professional interests had grown. I was still immersed and engaged in the field of educational development through my work at UBC, but wanted to pursue coaching and entrepreneurial activities.

To honour my changing interests and new career goals, I made a number of decisions:

- enrolled in Tracy Timberlake’s course for new entrepreneurs (Tracy was a guest on the Introvert Entrepreneur)

- sought educational consulting opportunities

- registered and then completed the Gallup’s Accelerated Strengths coaching course

I am now a Gallup Certified Strengths Coach and very energized by this journey I’ve begun.

Thank you to my everyday leaders.

**************************************

Note 1: For anyone who knows StrengthsFinder, you probably won’t be surprised to know that my Top 5 are: Learner, Intellection, Input, Achiever and Connectedness.

Note 2: I am a regular listener to all the podcasts I mentioned above because I learn SO much from these. I also learn a great deal from other podcasts, but the ones I’ve highlighted are that had a distinct role in my career transition.

Note 3: This post is inspired by Bonni Stachowiak’s blog post in which she wrote about podcasts’ contribution to her personal knowledge management system.