The issue of visual literacy has always been of interest to me, particularly because its power is often overlooked in our everyday lives. As an English teacher, I feel that I am more aware of the power of language, but the multi-layered efforts behind imagery is less clear. While reading Lesley Farmer’s article, I was amazed by the level of construction that every advertisement employs. From the effects of text selection, to line placement, and perspective between objects, I feel I had never really considered visual text in such detail. As Farmer states, “In order to convince the viewer of a specific idea, mass media producers who under-stand the language and connotations of visual literacy can manipulate images to elicit desired responses – a strategy that is used increasingly with the advent of digital tools (30)”. To a certain extent this is rather disconcerting because I’d like to believe that I am educated enough to be conscious of such manipulations. The truth? Without a course in media production, I am likely missing some key elements… How am I then to properly guide my students to become critical of mass media? Yikes…

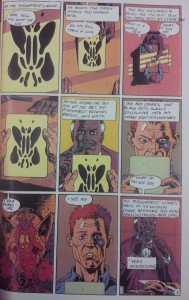

As a precursor to a discussion of propaganda during the Holocaust, (I taught Maus) my grade nine English classes investigated stereotypes in advertising. I divided the class into six groups and presented each group with a series of photos. Some groups looked at women in advertising, others at men, teenagers, teachers, and so forth. While the students were quick to identify the stereotypes at play in the pictures and perhaps why these stereotypes prevailed, one area which we did not touch on at all, (now I feel it would have deepened our understanding) was some of the finer artistic choices.

I can only blame my own naivety for not providing my students with this opportunity, but after reading this article I am thankfully, more informed. I suppose as with any teaching endeavour, one must arm themselves with the necessary knowledge to at least begin a dialogue within the classroom. As our group will explore in our presentation, this awareness begins by examining the minute details behind advertisements and their implications. Being conscious of selection choices and editing procedures (especially helpful when considering issues of body image…) on behalf of the producers, provides a strong starting point for critical analysis. Farmer’s article is very useful and breaks down the elements of visual literacy into manageable pieces. Hopefully, in my future classes, I can help my students navigate through the maze of imagery that saturates their lives. Wish me luck!

By: Ashlee Petrucci (Blog Post #1)

Works Cited

Farmer, Lesley S.J. (2007). I See, I Do: Persuasive Messages and Visual Literacy. Internet @ schools, 14(4), p. 30-33.