Over the course of this education program, I have done a lot of thinking about what it means to be an English teacher in the current day and age. In his article “A Curriculum for the Future, Gunther Kress puts into eloquent words all that has been swimming around in my head. I truly believe that what he outlines as a new direction for curriculum in general and for English classes specifically is one toward which we should all be moving.

He starts off by prefacing his argument with the suggestion that “the presently existing curriculum still assumes that it is educating young people into older dispositions, whereas the coming era demands an education for instability…. When tomorrow is unlikely to be like today and when the day after tomorrow is definitely going to be unlike yesterday, curricular aims and guiding metaphors have to be reset” (133-4).

He then delves into a lengthy explanation of what the new curriculum should entail. Words that are frequently used are creativity, multiliteracies, innovation, adaptability, ease with difference, comfortableness with change, instability, agency, transformation, communication. These words remind me of a statement I made in this class a few days ago, about how in teaching English we are moving toward giving students the skills to talk about, write about, think about, and interact with content rather than simply teaching them the content itself. Rather than learning being top-down and content focused, I think that learning needs to become student-centered and innovative. Kress takes my point of view even further by arguing that the driving force of this new curriculum should be design. Students should be learning to take what they know and transform it, design it to reflect their interests and to make it serve as a means for their interaction with and decoding of their personal environments and the globe as a whole.

Kress states that “What remains constant [in the new curriculum] is the fundamental aim of all serious education: to provide those skills, knowledges, aptitudes, and dispositions which would allow the young who are experiencing that curriculum to lead productive lives in the societies of their adult periods” (134). What has changed is the needs and requirements of society. Active citizens now need to be able to decode vast amounts of information from a wide variety of sources and recorded using a variety of literacies in an ever-changing environment and comment on it, interact with it, and produce something new, thoughtful, and useful.What arises from this need is an “Education for instability” (138), in which students are given the tools they need to adapt to this transforming world and to be the agents of their own designs and processes. Kress states, “Design makes the learner agentive in relation to her/his interests in a specific environment and in relation to the resources available for the production of that design. He or she is transformative, creative and innovative. Design asks for production of the new rather than replication of the old. Thus putting ‘design’ at the centre of the curriculum and of its purposes is to redefine the goal of education as the making of individual dispositions oriented towards innovation, creativity, transformation and change” (141). This idea of agency made me think about the principles introduced in today’s class on Gee’s article “Good Video Games and Good Learning.” I think that a lot of the learning principles he outlines apply to the fundamental concepts of Kress’ new curriculum. Identity, interaction, production, risk taking, customization, agency, and situated meanings all apply to the notion of a curriculum of design within instability; ideas of transformation, agency, design, change, understanding, openness, communication, adaptability, innovation, multiliteracy, and creativity.

I think that a multiliteracies approach in the classroom that focuses on design through inquiry, agency, and creativity is one in which students will be shaped into individuals that are competent and skillful at navigating our developing and “unstable” current and future worlds.

– Rebecca Thomas

Gee, James Paul. “Good Video Games and Good Learning.” Phi Kappa Phi Forum 85.2 (Summer 2005): 33-37. Web. 13 July 2014.

Kress, Gunther. “A Curriculum for the Future.” Cambridge Journal of Education 30.1 (2000): 133-145. Web. 16 July 2014.

Tags: Uncategorized

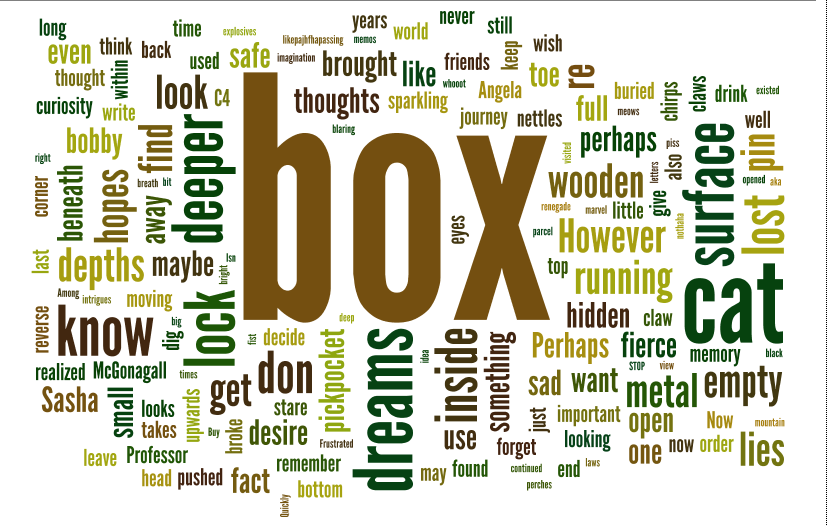

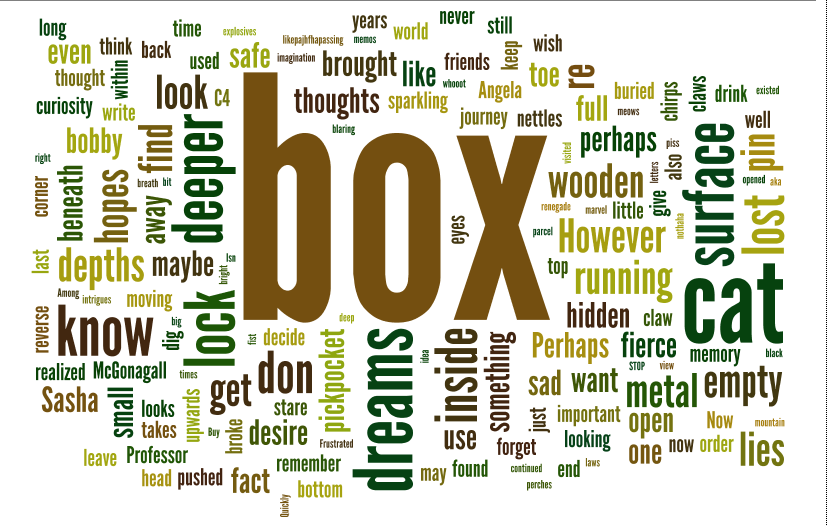

My project changed like 15x before I settled on this. Not what I started out wanting to do, and I was initially not very happy with it, but it’s growing on me.

Media Project 2 Writeup

Tags: Media Project II

In Baron’s article “Instant messaging and the future of language discusses the importance in distinguishing “creativity and normative language use”, the author suggests that there is a concern regarding whether younger students, who are early in adapting instant messaging language might hinder the acquisition of formal writing skills. This article was written in 2005, and engagement in instant messaging has come a long way with with the invention of smart phones. During our class discussion we talked about the difference between autocorrect and intuitive text. I argued that the intuitive text technology in smart phones actually promotes literacy. I have two reasons for this. The first is a personal experience I have had. I have seen myself shift back to formal spelling in most of my IM conversations on my phone, and it makes me aware of spelling words correctly since I need to have an idea of how to spell something to be able to swype the word. I have reverted back to using correct spelling simply because it is easier that tapping the tiny keyboard on my screen.

The second is an example that I shared in class. My mom recently bought a smartphone, and prior to that she owned a flip-phone that she only used for calling out and receiving phone calls. She was not comfortable with texting due to her perception of her English language literacy levels. However, since familiarizing herself with the smartphone and the app, “WhatsApp”, she started to message me. She told me that she loved that her phone gave her word suggestions and spelling corrections, and many times she will say to me “Angela, I learned how to spell another word today!”

Furthermore, after having the opportunity to view John Mcwhortor’s TedTalk during class. His asserted that IM/texting language or what he calls “fingered speech” showcases young people’s ability to be flexible and intelligent in the way they negotiate their use of the English language. I especially enjoyed his point that people who use “fingered speech” are literate in formally written English and can switch between different registers. However, if you were to ask an adult who has not had experience with “fingered speech” they might not be able to decipher what is being communicated.

In short, I think it important for students to understand the time and place for the use of different registers in language and as teachers, we definitely need to be cognizant of teaching students which spaces allow for different registers as it arises in specific cases in our classroom, but overall, in my experience during practicum, most students are able to differentiate their use of IM language from formal language in their written work.

Works Cited:

Baron, Naomi S. “Instant messaging and the future of language.”Communications of the ACM 46.7 (2005): 30-31. Web. 8 July 2014.

John McWhorter TedTalk: Texting is killing language! JK!!!

— Angela Lee

Tags: computer-mediated communication

Greetings fellow English Extrapolators! (Attempting a wink towards Carl Leggo here…)

Here is our second media project.

MediaProjectIIGeorgeandCo

Adapt the Adapted

-George, Leona, Dalyce, and Naz

Tags: Media Project II · Uncategorized

De Castell and Jenson’s article discusses, with admirable candour, the difficulties in representing and conveying “educational” content through the medium of video games. They describe the process of designing a game called Contagion that seeks to address several public health issues, namely the class dimensions of disease transmission and state policies vis-à-vis virulent outbreaks. From their description, it is made to sound like a junior action/adventure approach to epidemiology or the “Social Determinants of Health” (but with the dystopic glamour of a pandemic panic!)

The candour I alluded to above instantiates in the authors’ admissions that the “funnest” parts of the game were the ones that touched on the social-political context of the game in only the most cursory or perfunctory ways (126). For example De Castell and Jenson describe a driving game portion of the larger game wherein players drive “through the streets of lower Pyramidea [the name of the city-state that constitutes the game world] at night, trying to locate and treat patients identified as needing assistance, while avoiding the patrolling…vans” (126). While this scenario may seem relevant to the social-political context of the game as I’ve described it, the authors allow that, essentially, “it’s just another driving game” (126).

De Castell and Jenson’s admission that the most appealing parts of the game contained the least “content” in terms of educational import lead to their greater point that the true “educative” aim of any game is, in sense, the “fun” itself:

The learning goal is such a game is simply to play it, to be in that setting, as an active and engaged participant, stringing together the parts, none of which is self-contained, but all of which can be fitted together to make up a richly educative whole (130).

The authors also go on to decry the utility-driven, instrumentalist vision of education that demands concrete measures for the displaying of learning processes that are often highly complex, social, internally-experienced, and not amenable to quantification. In this I completely follow them; I, too, think we need to resist the injunction to constantly test and show what we’ve accomplished as students and teachers. However, the question that is provoked by this line of thinking, precipitated as it has been in this article by a discussion of educational games, is what purpose the designation of “educational” content serves. Presumably, students are “active and engaged” participants in the settings of the commercial games that they play outside of school. If what educational games supply to them is something they are learning from the games that they play anyway, then is the purpose of an educational game an ethical one at its core? De Castell and Jenson do not explicitly state this to be the case, but the upshot or corollary of continuing to advocate for educational games (while admitting that they do very little to convey content) is to argue that there are suitable or unsuitable games for children of a certain age. Of course, this should not be a controversial idea. The horrific violence and virulent sexism that we see in computer games necessitates that we exercise some degree of gatekeeping. If we (and, presumably, the authors) agree that the project of edification (or, at the very least, protection from oppressive ideas) is defensible, then a careful articulation of that position might have accompanied an argument advocating gaming for gaming’s sake.

Works Cited

de Castell, S., Jenson, J., & Taylor, N. (2007). Digital games for education: When meanings play. Situated Play, DiGRA Conference, Tokyo, Japan. 590-599.

– Peter MacRaild

Tags: Uncategorized

Tags: Media Project II

In his article “A Curriculum for the Future”, Gunther Kress writes that a radical shift in thinking and curriculum in ELA classrooms is due to occur in response to the different needs of the contemporary adult in 21st century society. He states that the world has changed so much that the 19th century model of education is just not applicable anymore. Kress calls for a shift in curriculum from an education for stability to one for instability:

“Associated with this are the new media of communication and, in particular, a shift (parallelling all those already discussed) from the era of mass communication to the era of individuated communication, a shift from unidirectional communication, from a powerful source at the centre to the mass, to multidirectional communication from many directions/locations, a shift from the ‘passive audience’ (however ideological that notion had always been) to the interactive audience. All these have direct and profound consequences on the plausible and the necessary forms of education for now and for the near future.” (138)

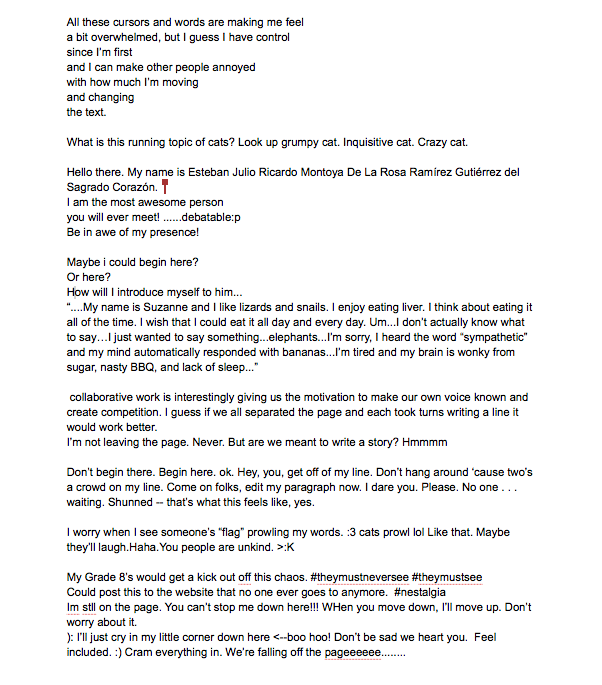

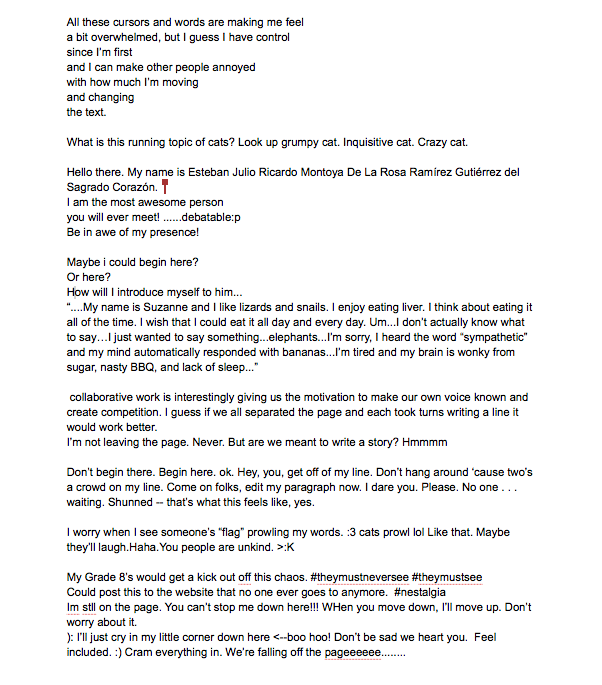

The notion of a multi-directional communication and a shift to an interactive audience is what stands out for me in Kress’ assertion. As such, I have designed an activity for use in an ELA classroom that allows students to be creators and participators in such a communication. Using a variety of online tools, students are able to work collaboratively to create a co-authored product. The product can be inspired by whatever you are currently studying in your class—it could have a thematic or topical connection to a literary text, or it could simply be a pre-writing exercise begun with a prompt. The only stipulation is that the activity be carried out in silence thus disturbing the notion of passivity and activity, telecommunication and proximity, and the product of the individual vs. that of the group. So far in this class we have explored the following topics:

• modes of representation in ELA classroom/21st century literacy

• visual literacy and rhetoric

• media literacy

• social media and the notion of participation

• new literary forms/e-literature

• computer mediated communication

• gaming

I also designed this activity to address pieces of all of the things we have discussed thus far in regards to these topics.

Activity:

In a group setting, students will work in silence to participate in a back channel conversation while they co-author a textual document with a particular purpose. This purpose may be nebulous or fixed. The backchannel application I use is Today’s Meet and the document will be created in Google docs. Each student will be invited to share the document and simultaneous editing will be possible. Google docs also has a “chat” capability which may or may not be used. I will begin the class by explaining the task and the “rules” as well as work with the students to determine the loose direction of the task. Once we have a sort of trajectory, we will begin and allow the interaction to take us where we will. The backchannel and the doc will be projected on the screen for all to witness (though it occurs to me that maybe just the backchannel might be appropriate). After the time is up, we will take the product (the created text) and render it in a text visualization tool. A teacher could then take this one step further and have the students create a found poem from the word cloud that serves as their reflection on the task.

After I execute this today, I will post the products as an exemplar.

-gunita.

Works Cited:

Kress, G. (2000). A curriculum for the future. Cambridge Journal of Education, 30(1), 133-145.

The Products:

The Today’s Meet chat transcript was lost to the ether but, interestingly, the group chose to communicate via in-doc Google chat instead.

Tags: computer-mediated communication · e-literature · Lesson Plans · multiliteracies · Presentation · Seminar Prompts · Social Media · Visual Literacy · Weblog Activities

The Reality in Fantasy:

A Digital Dialogue

In David Buckingham’s Media Education (2003), he argues that “media representations can be seen as real in some ways but not in others: we may know that something is fantasy, yet recognize that it can still tell us about reality” (58). Taking Buckingham’s notion several steps further, the philosopher Slavoj Zizek claims that it is only through fantasy that we are able to approach so-called reality (“Slavoj Zizek on the Matrix and Video Games”). To my mind, nowhere is the mediated dialogue between reality and fantasy staged more consistently than in digital gaming. Indeed, digital gaming does not separate fantasy and reality but rather associates them for a tidy profit.

Fantasy, in these instances, has the potential to jump out of traditional categories and illustrates the volatile and productive association between “illusion” and “reality”, one of dependence and solidarity. When we isolate fantasy from reality, we limit a wide range of experience and expression that can arouse activism and nourish new modalities for change – deadly serious ones not because they elude the logic of traditional barriers and hierarchies but because fantasy looks at reality from unique and inverted angles. And it is precisely these angles of fantasy rubbing up against the edges of reality that lets us theorize and try to represent new dimensions and thought.The connection that digital gaming draws between these two categories suggests that, for a gamer, it is not about reaching a condition that no longer requires illusions, but instead imagining a reality where fantasy is possible. And the fantasy that seems particularly impossible to recognize in our present is the fantasy Marx refers to as the “species life” of society – those occasions where individuals regard themselves as members of a community, and, therefore, where their actions are consciously performed as communal beings (Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts 33-34). The fantasy we refuse to entertain is the reality of social production: against the backdrop of a global economy (where the pervasiveness of commodification is matched only by its intangible abstraction, where the clothes I purchase (re)produce exploited spaces and lives, where the figures with whom I may identify are “the gamer”, the “blogger”, and “the first person shooter”, and where social relations are virtual but no less concrete for all that) the capacity to consciously reconfigure our relationship to our own labor and consumption has never been more imperative. Ironically, maybe the place to start is in our “fantasies” rather than our “realities”.

Works Cited

Buckingham, David. Media Education. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2003. Print.

Marx, Karl. “Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844” in The Marx-Engels Reader. 2nd

Ed. Trans. Martin Milligan. Ed. Robert C. Tucker. New York: W.W. Norton & Company,

1972. Print.

“Slavoj Zizek on the Matrix and Video Games.” YouTube. 17 Nov. 2011. Web. 24 Nov. 2013.

Tags: Uncategorized

“A Girls’ Day Out” And Everyone’s invited:

E-Literature = Interactive or Directive?

There is an old aphorism declaring “Laws, like sausages, cease to inspire respect in proportion as we know how they are made.” This piece of conventional wisdom presents a useful foil around which to discuss Kerry Lawrynovicz’s interactive e-literature poem “Girls’ Day Out” (2004) – a prominent goal of which is precisely to foreground the process of production. I want to suggest that her poem as well as similar forms of e-literature attempt to undermine the stereotypical attributes of autonomy, individuality, and elitism accorded the literary text as a fetishized object and to the cult of the writer as an artistic genius through an emphasis on process/concept over product/author. To stretch the aphoristic analogy, then, we might say that modes of conceptual interactive e-literature like that displayed in “Girls’ Day Out” critique the institutional nature of literature as a practice: a motley assortment of unappetizing scraps of language are ground together, stuffed into a virtually transparent casing that ensures a recognizably intelligible form, and is then presented as a hypostasized product that effaces the unseemly labour of literary production.

Lawrynovicz’s poem, in contrast to conventional literature, accentuates self-referentiality, reflexivity (i.e., writing about writing), intertextuality, the procedural generation of language, and/or the strict adherence to a governing principle or controlling conceptual system. Yet perhaps the most controversial technique of her poem is the “repurposing or detournement” of “found language” wherein “previously written language comes to be seen and understood in a new light” (Dworkin xliv). Here, the initial prose poem describing the idyllic horseback adventure of two young girls is laid bare with the click of a mouse, literally exposing a buried narrative of serial murder with phrases appropriated from a newspaper article that chronicles the real-life events and deaths with which the shifting text engages. According to Kenneth Goldsmith, this literary practice of appropriation operates along the same lines as Marcel Duchamp’s notorious reframing of gallery space, a critique directed against the sacrosanct status of the art object and the rarefied notion of the process of artistic production. Thus, works like Lawrynovicz’s stress the aspects of recycling and selection inherent to literary production and to the significance that context plays in the conveyance of meaning: if you change the context of reception or audience, you change the meaning. Consequently, Goldsmith envisions the role of the conceptual writer as that of a cultural “arbiter”, a filter of “taste” (xix).

In my opinion, however, Lawrynovicz’s “Girls Day Out” provides a more nuanced and critical representation of conceptual writing in general and of the interactive e-literature writing movement in particular, in contrast to the laudatory advocacy of conceptual writing by Goldsmith and others. In many ways, Lawrynovicz’s text is a self-criticism of conceptual writing and interactive e-literature as institutionalized practices in and of themselves. In fact, I read her text as an interactive conceptual critique of interactive conceptual writing. That is to say, a critique deeply implicated in what it is criticizing; at once critical and perplexed, simultaneously ironic and sincere. For instance, the unsettling imagery of sheltered complicity riding unwittingly over the bodies of the murdered suggests on some level that such a protected and privileged existence is predicated on the exploitation and vulnerability of others. In addition, the interactive and suspenseful quality of the piece invites the reader to explore another variety of complicity: the gruesome unfolding of the narratives in the poem mirror a sensationalized account in the media where an audience’s interest is a contradictory mixture of revulsion, horror, and macabre fascination. Finally, just as a story in the media can take on a life of its own and obscure the original issue at stake, so too does the sheer intricacy of the formal design of Lawrynovicz’s poem deliberately begin to overshadow the murdered women and transform a dedication into an aesthetic, interactive, and conceptual experience. The blending of social critique, suspenseful narrative gimmicks, and “interactive” (or complicit) audience participation ambiguously conflates these often mutually exclusive practices and suggests we critically engage with the representational and aesthetic methods of e-literature and submit them to the same questions that we would political platforms, to the issues of class, gender, ethnicity, or agency, for instance.

Works Cited

Dworkin, Craig. “The Fate of Echo” in Against Expression: An Anthology of Conceptual

Writing. Ed. Craig Dworkin and Kenneth Goldsmith. Evanston: Northwestern University Press,

2011. Print.

Goldsmith, Kenneth. “Why Conceptual Writing? Why Now?” in Against Expression: An

Anthology of Conceptual Writing. Ed. Craig Dworkin and Kenneth Goldsmith. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2011. Print.

Tags: Uncategorized

“What you learn when you learn to play a video game is just how to play the game”. James Paul Gee outlines this as a dismissive statement from people who devalue the learning benefits of playing video games in his article “Good Video Games and Good Learning”. He explains that students should be “learning how to play the game” within their classes in school (Gee, 2005, p.34). As part of my teaching philosophy I aim to guide students in learning how to be self-aware of their own learning styles and how they best acquire and negotiate knowledge. Education is much more than learning the content. I believe that students will be much more successful when they can identify how they learn, instead of solely what they have learned. I strongly agree with Gee’s article as he argues that there are many valuable aspects of “video games [and how they] incorporate good learning principles” and that educators should investigate this idea to engage and motivate students in the classroom (p. 34). I am a strong proponent for promoting and facilitating fun and learning conjointly in school. I strongly agree with the learning principles that he puts forth in his article. If teachers can incorporate some of the learning principles Gee identifies, then they can assist students in navigating their educational endeavours.

Reflecting on my practicum, I had the opportunity to teach Social Studies 8, and it was definitely out of my comfort zone since I have only been prepped to teach English. I had to stop myself from worrying and instead ask myself “How can I make this fun, for both, my students and I?”. During a unit on Feudalism and the Middle Ages, I challenged myself and the students by creating a final project where they got into groups and had to write a script for a mini-play depicting a conflict that could occur within the hierarchy during the time period and then perform it for the classmates. At the end of the unit, I asked students to fill out an anonymous feedback slip and students communicated that it was one of the more exciting projects they have completed. I received comments that expressed how they enjoyed the flexibility and creativity that the project allowed and their positive regard in being to able to verbally and kinesthetically communicate the content they learned. As I read Gee’s article, I made many connections with this experience. To name a few of them, many of the students enjoyed this project the same way some people enjoy video games. Before they started the script writing process, I asked each student to be responsible for creating a character for themselves by completing a character bio worksheet, which matches with Gee’s learning principle 1. “Identity”. Students became committed to their self-designated characters within their project (p. 34). It also offered “challenge and consolidation” since it allowed students to create their own problem or conflict and write a solution to resolve it, while applying and synthesizing the content, which creates “a mastery” of key concepts from the unit. As well, this project connects with principle 2 and 3, “interaction” and “production” (p.34,35). Students were able to work together to make decisions and offer feedback in the script writing process.

Overall, the question Gee poses about how video game creators and educators ask a similar question of “How do you get someone to learn something long, hard and complex, and yet still enjoy it?” is definitely worth taking time to consider (p.34). I think it would be great if we could harness the enticement and motivation video games create and bring that same attitude into the classroom. It would definitely change the classroom environment into a much more engaged place where students will be more invested in learning.

Gee, J. (2005). Good Video Games and Good Learning. Phi Kappa Phi Forum, 85(2), 33-37.

Angela Lee

Tags: gaming