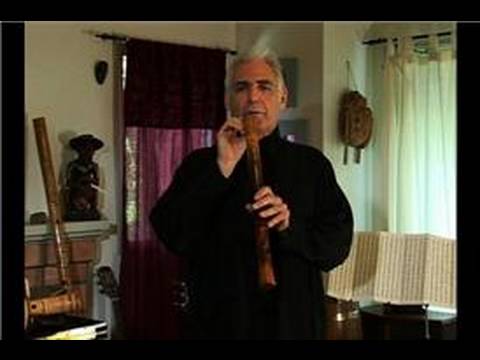

You’ve decided to study the shakuhachi – a traditional flute from Japan.

You know that it’s steeped in history and tradition, but what’s really grabbed your attention is its focus on meditation, using the sound of music. You have some prior experience with Western music instruments, and you can even read the notation of Western Art Music (WAM). But WAM’s steep learning curves and obsession with theory, history and technique ultimately seems hollow, for some unknown yet deeply personal reason you haven’t been able to fathom. In contrast, the shakuhachi appears to be nothing more than a simple stalk of bamboo with five finger holes and its music moves at such a slow pace that there is an ocean of time to think about the next note. The look of the bamboo surface is mottled and “natural”, unlike the gleaming machinery or stained-wood perfection of WAM instruments. And yet, despite its physical and musical simplicity, many claim that shakuhachi is the singular and uniquely musical voice of Zen Buddhism and its promise of enlightenment (kenshō 見性)

A Traditional Lesson

The success or confusion of your first lesson will be determined by its context. Will it be conducted by a traditional sensei (先生) or in a Western teacher?

If it is a traditional Japanese music lesson, then be prepared for practically no conversation. After a friendly greeting, the sensei plays a single note and then shows you the fingering. You play the note. “Again (mo ichidō; もう一度),” he says. You play the note a second time. “Again”. You…Well, you get the idea. Before you realize it, you become immersed in mind-numbing repetition, and yet the teacher has an exemplary sound and an almost spiritual presence. So you persevere.

You’ll very likely be surrounded by fellow students, each waiting their turn. If you felt sheepish about making your first, halting sounds in front of them, your fellow students are far too wrapped up in their own concerns to give any attention to your failings. (Your mind might flash back to those many master classes you endured, both as player and witness, surrounded by fellow players.) As you comply over and over with your sensei’s constant demand for exact repetition, you might recall the regimen of karate lessons. Those martial art students make the same thrusting gestures over and over again, while counting out the repetitions, all under the steely-eyed guidance of the sensei. Those gestures are called kata (型 or 形) and now you see the same operation at work in a music lesson.

A Western Lesson

If you take a shakuhachi lesson from a westerner it will likely have the same give-and-take as a regular WAM music lesson, with plenty of time to ask questions and make comments. You will have access to many turorials and internet sources that give you the rudiments and musical background, and the teacher will likely inspire you with the same magical sound and flawless technique as the traditional sensei. And yet, you feel that something might be missing. You may sense that the lesson is missing its cultural context, its unspoken frame that provides the Zen-like (zendō 禅道) experience.

In both scenarios, there is one huge, empty space (and I’m not talking about the Zen space (mu 無) – a Buddhist background on which to place the musical meditation experience. I suppose it’s possible to learn a music instrument without delving into its cultural context (such as the Western Art Music piano without reference to its 19th century salon roots, or Bach’s cantatas without an understanding of Lutheranism) but I know from experience derived from my years as an undergraduate and then graduate music students with a minor in Buddhology that I couldn’t possibly approach the shakuhachi without this ocean of knowledge.

Your First Sound

You put the flute to your mouth and blow across the top of the open hole, like a pop bottle. If you’re lucky, you’ll get a sound right away. This beginning procedure is very similar to the first lesson on the Western flute where you are assigned the task of making sounds on the mouthpiece detached from the body of the flute.

The sensei presents you with your first piece of music. Of course, it’s in traditional Japanese notation, but you quickly discover that it is solfeggio, where each note is actually a simple syllable that represents a specific pitch. He then points to the first note and plays it. Then it’s your turn. Again, and again. His sound is edgy and full; yours is breathy and anemic. And here’s where it gets interesting.

Your First Buddhist Sound

You may or may not be told that your first horrible sounds are also your purist Zen sounds. Rough (wabi), tentative (impermanent), breathy (i.e., the sound of nature, like the soughing of wind in trees) You might recall the title of a famous book by Shunryu (not Daisetsu Teitaro) Suzuki, “Zen Mind; Beginners Mind”.

Once you have established a sound that can be reliably duplicated you may or may not be told to hold that note for as long as you can breathe out. Think of a half note, where the metronome marking is “quarter note = 30 BPM”. Breath, and breathing seems to be the key to success. You may have heard of the same concern for breath control in yoga classes, where you assume a posture and then breathe slowly and deeply. In both worlds, the diaphragm comes into play. In Japan, it’s called tanden ( 丹田), the centre of the soul (and the point of sacrifice in the hara-kiri ritual). To put it crudely, if your stomach (hara 腹) is not ballooning, you’re doing it wrong.

So what kind of sound should you be making? Definitely not the kind that undulates with vibrato, the essence of the Western flute sound, as well as a host of other instruments. The sound should be straight, in tone and pitch. Your sound will also likely trail off after a moment or two, like a decrescendo. I think that’s good, because I believe the sound of the shakuhachi was (and is) inspired by the natural decay of a ringing bell, especially the hand-bells (rei 鈴) played by Buddhist priests during their rituals, the bowl bells (keisu 鏧子) during their chanting, and the huge hanging bells (bonshō 梵鐘) found in their temple compounds. Even the titles of the sacred solo music have the word bell (e.g., Reibo 鈴慕) in their names.

As your breath flows steadily out of your body, and the sound emanates simply and directly, you are asked to concentrate only on the sound, the sonic manifestation of your silent breath. During the time of one breath, time should seem to stand still. The next tone, a repeat of the first, should not be played right away; otherwise you’ll feel light-headed and may even faint. Take your breath in as slowly as you breathed out. It is perferable to stand or sit up straight, allowing an unimpeded expansion of the diaphragm. If you sit in Japanese seiza (正座) style, kneeling with your legs under you, the one-tone exercise will turn into an unsolvable Rinzai puzzle koan (公案): “Can I realize one-ness with my one note while my legs scream in pain?”

When you can reliably make a flute sound, you will be shown how to use your fingers to flick a finger-hole open and closed, in the quick manner of a mordent, in order to initiate the sound. This is referred to as a strike (atari当る). Although many see this word as a common term in Japanese martial arts, it is also used in the ringing of bells.

Matsuo Bashō (松尾 芭蕉) described it best when he wrote the following haiku (俳句):

Temple bells die out / the fragrant blossoms remain / a perfect evening!

kane kiete / hana no ka wa tsuku / yūbe kana

鐘消えて花の香は撞く夕哉

Next Lesson

Two notes, connected together in one breath. Coming up in a future blog entry.

Readings

Andreas Gutzwiller (1991) “The world of a single sound: basic structure of the music of the Japanese flute shakuhachi,” in Musica Asiatica, 6, pp. 36-59

Jerrold Levinson (1997) Music in the Moment

John Singleton, editor (1998) Learning in Likely Places: Varieties of Apprenticeship in Japan

Jay Keister (2008) “Okeikoba: Lesson Places as Sites for Negotiating Tradition in Japanese Music,” in Ethnomusicology, Vol. 52, No. 2 (Spring/Summer, 2008), pp. 239-269