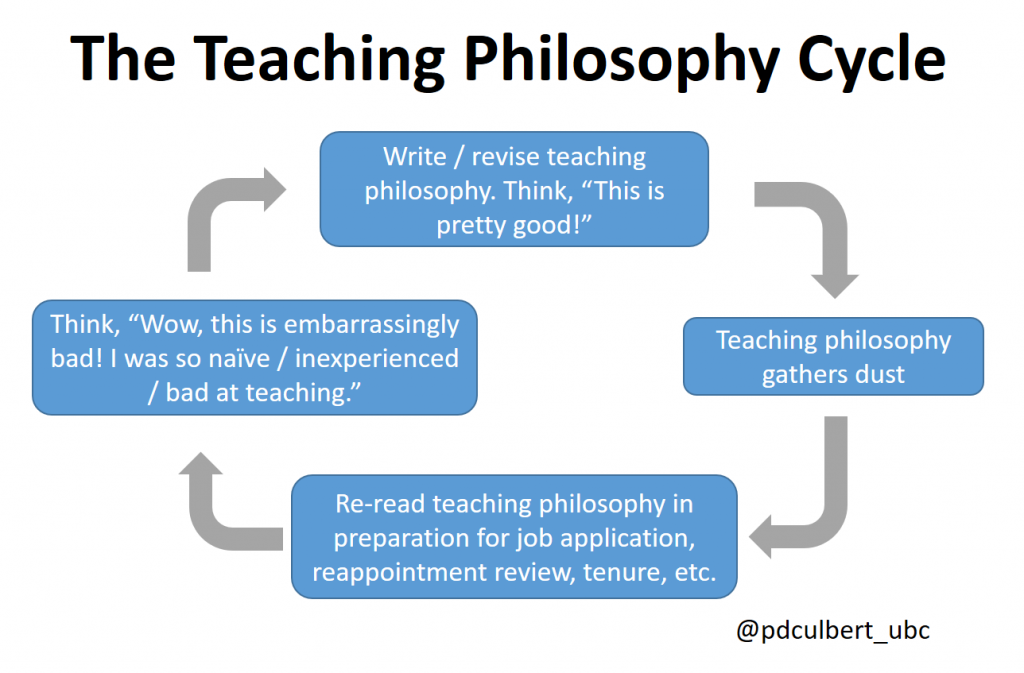

Teaching philosophies are unique documents. They are incredibly personal and thus quite challenging to write. They also behave a bit as a diary, reflecting ourselves from a very specific place and time. It’s been over a decade since I wrote my first. I’m not quite sure where that original document lives, which is all the better, as I imagine a re-reading would involve a fair amount of cringing. I’ve revised my philosophy a number of times, usually for job applications but most recently for my tenure package. I (somewhat facetiously) made a graphic of this revision cycle.

This figure aims for a laugh, but at a deeper level, I appreciate having a document that grows and changes as I do. Each revision is an opportunity to reflect on that growth.

I’ve never shared my philosophy publicly, but I’m now feeling brave enough to do so. I can’t imagine any of this document will surprise colleagues or readers of this blog, but hopefully it will give readers some food for thought as they reflect on their own practice. Here we go:

As I revise this statement in summer 2020, the start of my fifth year as a faculty member at UBC, I appreciate the opportunity to reflect on how my thoughts on teaching have evolved in the 12 years since I first drafted a teaching statement as a graduate student. The one constant is my deep love of teaching and learning about the natural world. This goes back to my high school summers spent teaching “nature” to Cub Scouts in northern Wisconsin. In some ways, taking a group of undergraduates on a hike through the forest feels quite similar. The material is different, but my joy of watching students experiencing and learning about the natural world firsthand is the same. What has changed is that my philosophy has become more cohesive. As a graduate student, I could not elucidate an overarching theme of my practice. Since then, my teaching has coalesced around themes of evidence-based practice, compassion for students, and reflection and improvement.

Evidence-based practice

Throughout my academic career, I have sought out opportunities to study teaching and learning. As a graduate student and postdoc, I took a number of semester-long courses, such as Teaching Large Classes, The College Classroom, and Research Mentor Training. These introduced me to many great ideas, however the focus was on teaching practices, with little emphasis on learning theory or empirical research. I gained much from these courses, but over time I became more interested in the theory and empirical evidence underlying those ideas.

During my postdoctoral teaching fellowship at Middlebury College, I was introduced to Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) and the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning (CTML). CLT considers the cognitive load imposed upon learners by instructional materials, and CTML aims to minimize cognitive load through empirically-tested design principles. Both are supported by cognitive science, and it was refreshing to explore this literature and see a strong theoretical and empirical foundation tied to specific teaching practices. More recently, I have been exploring the cognitive science literature on effective learning strategies. Based on this literature, I have adjusted my classroom approaches to foster empirically-supported learning strategies such as retrieval practice and distributed practice. It is also important to me that students understand the evidence behind my course practices and classroom policies. My introductory lecture in my second-year course (FRST 211), is devoted to the science behind learning and effective learning strategies. This is in part to encourage students to be more efficient in their own studying, but also to explain that my implementation of daily clicker questions and weekly checkup quizzes are specifically designed to aid their learning and retention.

In addition to incorporating the findings of others, I am an active participant in the scholarship of teaching and learning. Supported by a UBC SoTL Seed Fund grant, I am examining whether the findings of CTML are still applicable for students who speak English as an additional language. This is especially relevant to our Faculty (which has high enrollment of international students) as well as my personal practice, as I frequently teach at the Faculty’s partner universities in China. I am also interested in the practice of two-stage exams and I am exploring how students’ performance or demographic factors may influence their perceptions of this approach.

Compassion and empathy

Over the past four years, I have become increasingly reflective on teaching with compassion and empathy. I had a relatively easy time as an undergraduate. My parents and siblings were all college graduates, so I had people to ask for advice. I never had any personal crises or traumatic experiences, significant physical or mental illness, nor did I face food insecurity or anxiety over how I would pay my rent or tuition. I was also confident in speaking to my professors and asking for assistance when I needed it. Because of this, I was initially unaware of challenges students might be facing outside of class. A number of interactions on Twitter have led to me thinking more deliberately about students in precarious circumstances. Recently, an educator made a flippant tweet about the number of students whose grandparents die around exam time. The replies were enlightening. Some noted that students might use this excuse rather than disclose that they were sexually assaulted, or experiencing mental illness, or otherwise unable to keep up due to difficult personal circumstances. Others spoke of the indignity of being required to produce an obituary as evidence of the death of a relative. Several spoke of how the kindness, compassion, and trust of their professors helped them get through difficult times. I now think about these things when, for example, I walk past the AMS food pantry. I know I am unaware of many of my students’ circumstances. If I am teaching 300+ students in a semester, odds are that several of them are facing significant challenges outside of class. In the context of COVID-19, I am sure those numbers are much higher.

In this context, I have significantly adjusted my classroom polices. I do not require documentation for missed classes or makeup exams, I simply take students at their word. This may seem naïve to some, but I am willing to occasionally give a student undeserved accommodation if it means students in genuine distress will always receive my unconditional trust and support. Having learned that first-generation and racialized students are much less likely to approach a professor to seek assistance or accommodation. Therefore, to make my views clear to all students, I added the following text to my syllabi:

Your Well-Being. In light of the policies above, please know that your physical and mental health are important to me. Family emergencies, physical or mental illness, personal crises, or childcare issues can significantly impact your academic performance or ability to meet deadlines. If academic or personal issues are severely affecting your ability to engage in this course, please contact me (by e-mail, phone, or in-person) and we’ll work on a fair resolution. I don’t need all the details of your situation, and you may also speak to someone in student services who will work with me to determine adequate accommodations without revealing sensitive information to me.

I explicitly ask a question about this policy in my syllabus quiz to be sure all students are aware. I freely exercised this policy during the COVID-19 pivot. I knew my students were facing many more difficulties than normal, and I was also frank about my own challenges (such as the sudden loss of childcare).

Reflection and improvement

I take a reflective approach to teaching, and I work toward continuous improvement of my practice. At the course level, I make notes at the end of each semester about changes to implement the next time. I also seek feedback from my students and TAs. These iterative improvements have resulted in a steady increase in my student evaluations for each courses I have taught more than once at UBC. At the broader level, my reflective process centers on my blog, Teaching Among Trees. Taking the time to write thoughtfully and deliberately about my teaching practice allows me to reflect on and evaluate the evidence behind my practice as well as consider my overall teaching philosophy (with the added benefit of sharing ideas with my peers). With regard to more general improvement and pedagogical knowledge, I continue to read books and journal articles as well as attend professional development activities. These range from individual seminars to more significant commitments, such as earning the Scholarship of Educational Leadership Certificate on Curriculum and Pedagogy in Higher Education from the UBC Faculty of Education.

Conclusion

Just as my philosophy of teaching has grown and changed up to the present, I know my views and perspective will evolve as I teach more students and gain more experience. My ultimate goal is to be an effective educator for all of my students. A focus on the science of pedagogy, the well-being of my students, and reflective practice should lay a good foundation. I am excited to continue this journey: teaching my students, learning from my students and peers, and sharing my knowledge and insights to support and promote excellence in teaching in the Faculty of Forestry and beyond.