This week in my graduate course on teaching and learning, we considered assessment. I was mentioning how, in undergraduate STEM courses, traditional approaches (e.g., grades heavily based on high-stakes exam and quizzes) are typically perceived to be absolutely essential. This idea is so ingrained that we don’t even consider that there could be alternatives. This isn’t the case for all of higher education though. As I was pointing out that we don’t grade dissertations, I was suddenly reminded of something from my past. During my postdoctoral appointment at Humboldt University in Berlin, I learned that German Ph.D. students receive a grade on their dissertation and defense. That struck me as absurd at the time, but it didn’t even occur to me that traditional grading in undergraduate courses might be similarly troublesome.

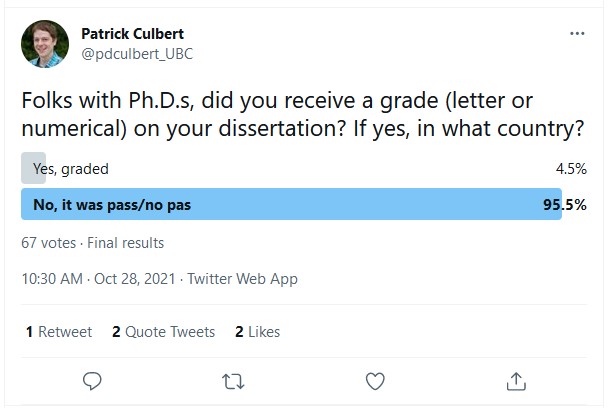

To confirm my memory, I posted a quick poll on Twitter . . .

Of 67 respondents, only 3 had their dissertation graded. So why don’t we grade dissertations? In fact, has this question even occurred to you? Take a moment to consider the following statements, none of which have I ever heard spoken:

- “If we don’t grade dissertations, Ph.D. students will only do the bare minimum required to pass.”

- “Without grades, Ph.D. students won’t be willing to incorporate feedback or revise their work.”

- “How can we assess a student’s learning without grading their dissertation?”

- “If some of a student’s experiments are unsuccessful or if some of their initial hypotheses are disproven, these failures must be reflected in their final dissertation grade.”

- “The ability to meet deadlines is an important career skill for scientists. Therefore, late dissertations will receive a penalty of 5% per day.”

- “Without a graded dissertation, how will employers be able to select the best applicant?”

I hope some of these strike you as almost comical. With appropriate support and mentorship, most Ph.D. students possess motivation independent of grades. Though it may vary with the highs and lows of the research process, this motivation is (mostly) related to students’ intrinsic interest in their field and topic of study. (Though the recognition afforded by the degree itself also serves as extrinsic motivation for most). Even without the grade, graduate students work hard. They re-do, revise, and revise some more. They seek out feedback from others as they work to improve their abilities and understanding. They pursue intriguing ideas and approaches, and while it may be a frustrating waste of time when some of those don’t pan out, there is no explicit penalty. They are empowered to take risks. They are taught that failure is normal, even if it is painful. They learn that an experiment with an unexpected result is often what leads to new questions, insights, or even breakthroughs. When they graduate and enter the job market, especially academia, potential employers will evaluate them based on their body of work and narrative assessments of their abilities (recommendation letters).

Those statements above seem almost silly when applied to a dissertation, but statements like these are typical justifications of the necessity of grading undergraduates. Why are our views on grades for undergraduates often in direct opposition to how we might perceive grading dissertations? Obviously, there are substantial differences between a Ph.D. and a B.S. or B.A.

- A PI may supervise only a handful of graduate students at a time, which hopefully allows for meaningful attention and feedback. While someone like me, who teaches hundreds of undergraduates each year, cannot possibly give that level of attention.

- I’m hopeful that most of our undergraduates are enrolled in programs that truly interest them, so they should have intrinsic motivation in many of their courses, but this certainly won’t be true for all courses or all students.

- Graduate students are in the process of becoming experts, while undergraduates begin as complete novices.

While recognizing these and other differences, I still find typical views of grading undergraduates dissonant with how we think about graduate students.

Clearly, it isn’t feasible or appropriate to treat all undergraduates like Ph.D. students, but I hope this comparison is enlightening and allows us to revisit our approaches to assessment and grading. Think about your undergraduate courses for a moment. What role does grading play?

- Does it encourage students to learn and explore with freedom and flexibility? Or, does it direct them to do precisely what you ask and nothing more?

- Does it stimulate and recognize student improvement?

- Does it incentivize students to revise and improve their work?

- Does it encourage students to cooperate and collaborate with their classmates, or does it promote an atmosphere of harmful competition?

- Are your students free to take risks? Or, do the grade-related consequences of a single failure force students to play it safe with predictable approaches?

I’ve been thinking quite a bit about ungrading over the past year. Ungrading doesn’t necessarily mean the total absence of grades, and it definitely doesn’t mean the absence of assessment. (Assessment and grading are often conflated, but they play very different roles in learning.) Jesse Stommel, a proponent of ungrading, writes:

“‘Ungrading’ means raising an eyebrow at grades as a systemic practice, distinct from simply ‘not grading.’ The word is a present participle, an ongoing process, not a static set of practices.”

Jesse Stommel, Ungrading: An Introduction

In the future, I’ll be sharing a number of posts on my experience with ungrading. In the meantime, if you want some fresh ideas and a range of alternative approaches to assessment and grading, I strongly recommend the book Ungrading: Why Rating Students Undermines Learning (and What to Do Instead) edited by Susan Blum. Each chapter is written by an educator who has rethought their approach to assessment and grades. These writers represent a variety of institutions including elementary and high schools, community colleges, small liberal arts colleges, and research universities. Their disciplines are also varied, including creative writing, chemistry, computer science, philosophy, and others. Their approaches to ungrading are similarly diverse. I will be revisiting this book as I continue to reconsider my own grading and assessment practices.

References

Blum, S. D. (Ed.). (2020). Ungrading: Why rating students undermines learning (and what to do instead). West Virginia University Press.

Ungrading: An Introduction. (2021, June 12). Jesse Stommel. https://www.jessestommel.com/ungrading-an-introduction/