Domesticar, doméstico, domesticidad… Al escuchar estas palabras las primeras imágenes que me vienen son las de un domador de fieras. Y casi simultáneamente, la amplia cocina de adobe y piedra de la casa de mi abuelo en una aldea perdida por Ávila, en medio de un secarral que hoy en día está deshabitado. Una cocina cubierta de telarañas y cuyo hogar (nombre que se le daba antiguamente a la chimenea) ha sido también tapado.

Domesticar, doméstico, domesticidad… Al escuchar estas palabras las primeras imágenes que me vienen son las de un domador de fieras. Y casi simultáneamente, la amplia cocina de adobe y piedra de la casa de mi abuelo en una aldea perdida por Ávila, en medio de un secarral que hoy en día está deshabitado. Una cocina cubierta de telarañas y cuyo hogar (nombre que se le daba antiguamente a la chimenea) ha sido también tapado.

Tales imágenes tienen que ver con la misma etimología de lo doméstico: el diccionario nos informa que proviene del latín domestĭcus, de domus “casa,” y hace referencia tanto a todo lo que pertenece a la casa, como a los animales que se crían en compañía del hombre (opuestos a los salvajes).

De este modo, cuando se sugiere que el mundo doméstico es de las mujeres nos imagino no sólo dedicadas a todas las tareas del hogar a lo largo de los siglos, sino también como animales salvajes sometidas “a la vista y compañía del hombre” (como nos indica, de nuevo, el diccionario). Animales de compañía, como los gatos que, según me dijeron hace poco los del control de plagas, ya no asustan a las ratas al saber que dejaron de ser cazadores salvajes hace mucho tiempo. Una lástima pues nos acompañan pero han perdido parte de su poder dentro del espacio común.

La idea de que el espacio doméstico nos pertenece a las mujeres y, por el contrario, el espacio público a los hombres es ciertamente muy problemática: aceptar la misma división del mundo de las dos esferas implicaría aceptar el (injusto) reparto laboral por sexos. Sin embargo, la frontera entre estos dos mundos –público y privado– es bastante porosa y siempre ha habido algo de una esfera que se escapa a la otra, interacciones y contactos.

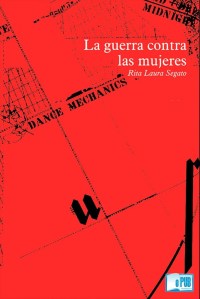

Ahora bien, retomar esta división para hacerla visible no siempre implica aceptarla. Creo que en muchas ocasiones posibilita el hacer notar y discutir tal reparto y la desigualdad que conlleva, paso inicial para transformarla. Segato propone empezar a nombrar esas historias del espacio doméstico de forma que creen una nueva retórica que haga frente a la dominante (la del valor de las cosas) y refleje lo que ella llama “política de los vínculos” y que asocia a lo femenino.

Pero, una vez más, dicha asociación puede resultar problemática. Al igual que cuando se asocia a la mujer a los cuidados (del hogar, de los hijos, de los mayores, de los enfermos, de las plantas, de los animales…) no podemos olvidar que es una labor histórica y arbitraria, al asociar a las mujeres a ciertos modos de sociabilidad y hacer política, no se debería perder de vista su carácter contingente. Nada hay que por nuestra fisiología haga mejores a las mujeres para los cuidados como todavía algunos se empeñan en asegurar, como tampoco en el pasado histórico las mujeres se encargaban de ello en exclusividad.

Muchos enfatizan que al ser nuestro cuerpo el que alumbra y sostiene la vida por medio del embarazo y el amamantamiento tal función biológica tiene un correlato social; sin embargo, según Durkheim todo lo social requiere una explicación de orden también social, no biológica. Por lo que tal vinculación de las mujeres a los cuidados tiene que ver más con los modos opresivos que se han usado históricamente para controlar a las mujeres en un espacio creado para ese fin. Tal espacio, además, ha ido adquiriendo una serie de significados relacionados con lo íntimo, lo privado, lo familiar y, hoy, lo individual, despojando de lo social y político al trabajo reproductivo (con el que me refiero no sólo a la procreación sino a todo el trabajo de cuidados y doméstico que facilita el sostenimiento de la vida). Según Bourdieu, “el orden social funciona como una inmensa máquina simbólica que tiende a ratificar la dominación masculina en la que se apoya” (Dominación 22).

El simbolismo de tal espacio doméstico es lo que Segato propone transformar adoptando una nueva retórica, a pesar del riesgo esencialista que implica nombrar lo que ha estado por tanto tiempo en los márgenes de la política en una supuesta naturalidad.

El peligro mayor, no obstante, está en la aceptación e inmovilidad de tal espacio donde seguiríamos siendo animales de compañía. Animales que al tomar el espacio público se exponen a recibir, como sabemos, acusaciones de ser salvajes que cometen actos vandálicos.

Parece necesario para la des-domesticación de lo doméstico y cambiar el rumbo de la historia de violencia contra las mujeres dejar de una vez atrás esa simbología del hogar y la mujer como su ángel o animal de compañía del hombre: seamos, en cambio, (todas y todos) compañeros salvajes.

In her chapter, “Patriarchy: From the Margins to the Center” (from La guerra contra las mujeres [2017]), Rita Segato goes further. We are all trained to be psychopaths now, she tells us, as part of a “pedagogy of cruelty” that is the “nursery for psychopathic personalities that are valorized by the spirit of the age and functional for this apocalyptic phase of capitalism” (102). Segato presents a brief reading of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange to make her point, though what she sees as “most extraordinary” about the film is that the shock with which it was received when it came out (in 1971) now seems to have almost totally dissipated. What was once taken as itself an almost psychopathic assault on the viewer’s senses is now just another movie; this shift in our sensibility is “a clear indication [. . .] of the naturalization of the psychopathic personality and of violence” (102). The narcissistic “ultra-violence” of the gang of dandies that the film portrays is now fully incorporated within the social order that it once seemed to threaten.

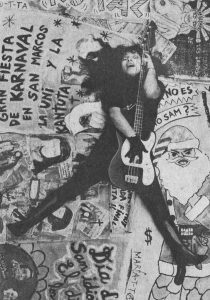

In her chapter, “Patriarchy: From the Margins to the Center” (from La guerra contra las mujeres [2017]), Rita Segato goes further. We are all trained to be psychopaths now, she tells us, as part of a “pedagogy of cruelty” that is the “nursery for psychopathic personalities that are valorized by the spirit of the age and functional for this apocalyptic phase of capitalism” (102). Segato presents a brief reading of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange to make her point, though what she sees as “most extraordinary” about the film is that the shock with which it was received when it came out (in 1971) now seems to have almost totally dissipated. What was once taken as itself an almost psychopathic assault on the viewer’s senses is now just another movie; this shift in our sensibility is “a clear indication [. . .] of the naturalization of the psychopathic personality and of violence” (102). The narcissistic “ultra-violence” of the gang of dandies that the film portrays is now fully incorporated within the social order that it once seemed to threaten. María T-ta had a very assertive discourse about female sexuality, and made it clear that she did “with her life and with her body what she wanted.” Her lyrics, presentations, interviews and publications evidenced her critique of machismo in Peruvian society. For instance, one of her songs describes the rape of a maid (a racialized woman from the Andes) by the son of a white family in a rich neighbourhood in Lima.

María T-ta had a very assertive discourse about female sexuality, and made it clear that she did “with her life and with her body what she wanted.” Her lyrics, presentations, interviews and publications evidenced her critique of machismo in Peruvian society. For instance, one of her songs describes the rape of a maid (a racialized woman from the Andes) by the son of a white family in a rich neighbourhood in Lima.

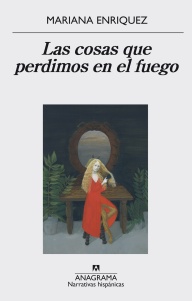

Femininity is all too often defined by the image (and so by the male gaze). Women are reduced to appearance, and judged in terms of the extent to which they measure up to some mythical ideal. Mariana Enríquez’s short story, “Las cosas que perdimos en el fuego” (“Things We Lost in the Fire”), presents a surreal and disturbing counter-mythology that explores what happens when that image is subject to attack, not least by women themselves.

Femininity is all too often defined by the image (and so by the male gaze). Women are reduced to appearance, and judged in terms of the extent to which they measure up to some mythical ideal. Mariana Enríquez’s short story, “Las cosas que perdimos en el fuego” (“Things We Lost in the Fire”), presents a surreal and disturbing counter-mythology that explores what happens when that image is subject to attack, not least by women themselves.