Peruvian Punks

y la minorización de lo femenino

By Fabiola Bazo

Student in the PhD program in Gender, Race and Social Justice at the University of British Columbia

As I read Rita Segato for this week’s discussion I thought, Damn! Why didn’t I have this text while I was writing about misogyny in the Peruvian punk scene in the 80s?

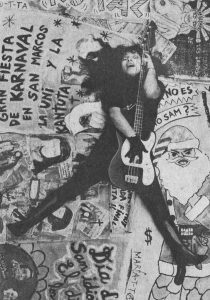

A punk scene sprouted in Lima in the 80s. It was a youth counterculture dominated by men and with clearly masculine symbolism and rituals. However, a small number of women dared to participate in this counterculture as musicians, among them Patricia Roncal, best known as María T-ta.

María T-ta had a very assertive discourse about female sexuality, and made it clear that she did “with her life and with her body what she wanted.” Her lyrics, presentations, interviews and publications evidenced her critique of machismo in Peruvian society. For instance, one of her songs describes the rape of a maid (a racialized woman from the Andes) by the son of a white family in a rich neighbourhood in Lima.

María T-ta had a very assertive discourse about female sexuality, and made it clear that she did “with her life and with her body what she wanted.” Her lyrics, presentations, interviews and publications evidenced her critique of machismo in Peruvian society. For instance, one of her songs describes the rape of a maid (a racialized woman from the Andes) by the son of a white family in a rich neighbourhood in Lima.

Her discourse was not welcomed in the punk scene, because the “dominant social thought” considered women’s issues to be a minority issue. As Segato argues, this minorización infantilizes women, and confines women/feminine issues to the sphere of the intimate, of the private, as a “minority issue” (2017: 91). Advancing feminine themes that were at that time considered intimate was against the punk canon. A canon that considered it “of little importance” to bring to the public sphere issues that affect women due to their condition as women.

To devalue María T-ta’s attempt to merge spheres, her project to de-minorizar feminine issues, punks claimed that María T-ta’s music and performative style was not serious. It was unpleasant and trivialized important social issues because “she had shit in her brain.”

Enforcing the punk masculinity mandate

“El mandato de la masculinidad exige al hombre probarse hombre todo el tiempo; porque la masculinidad, a diferencia de la femineidad, es un status, una jerarquía de prestigio, se adquiere como un título y se debe renovar y comprobar su vigencia como tal” (Segato 2018: 40).

“El hombre que responde y obedece al mandato de masculinidad se instala en el pedestal de la ley y se atribuye el derecho de punir a la mujer a quien atribuye desacato o desvío moral…el estatus masculino depende de la capacidad de exhibir esa potencia, donde masculinidad y potencia son sinónimos” (Segato 2018: 44)

Although the punk scene questioned authority, injustice and social conventions, it disciplined unacceptable behaviours sneakily with jokes and paternalistic attitudes, or overtly with physical aggression. María T-ta´s lyrics dealing humorously with women’s desire “infuriated” male punks who verbally and physically abused her while she performed. “The macho” was brought out when punks saw a woman who wanted to take command on the stage.

María T-ta awakened the demons of many people, who considered her “a woman out of control,” who did not know “her place.” So it became necessary to ensue the mandate of masculinity to exercise violence. Attackers would jump on the stage, and some thought their intention was “to make her disappear.” Or as Rita Segato would put it, she was violently disciplined by the patriarchal forces imposed on all of those who [must continue to] inhabit that margin of politics (Segato 2017: 96).

Paradoxically, a scene that considered itself libertarian, denouncing conservative values associated with the authority of the family, the Church and the State, rested on a patriarchal system demanding “sobriety” and “seriousness” as parameters of what was considered to be an “appropriate” punk. Women’s participation was tolerated only so long as it was subordinated to the mandate of masculinity and respected the division between the public and private spheres.

To be continued…

Works Cited:

- Segato, Rita. “Contra-pedagogías de la crueldad: Clase I.” From Contra-pedagogías de la crueldad (2018).

- Segato, Rita. “Patriarcado: Del borde al centro. Disciplinamiento, territorialidad y crueldad en la fase apocalíptica del capital.” From La guerra contra las mujeres (2017).

María T-ta y el Empujón Brutal, “El amor es gratis” (1986)

Y me dice mi mamá, “no te quites el disfraz ya verás que al matrimonio llegarás y por la avenida Arequipa no andarás”

Y me dice mi papá, “a tu cama sola y temprano regresarás

Y a la calle sin tu hermano no saldrás”

Me comenta mi abuelita, en los tiempos de Pepita, “así no eran las putitas”

Ya las primas y las tías, chismoseando a las vecinas se preguntan todo el día“¿En qué andará metida?”

Y mis amigas me marginan, con sus celos y su envidia

Ni siquiera se imaginan qué es tener vagina

En cuclillas y a escondidas, para gozar de la vida con mi costillo, confundida

¡Ya nos duelen las rodillas!

Ya sé lo que quiero, ya sé lo que quiero, ya sé lo que quiero,

¡no cuesta dinero y no da dolor ajeno!

Le contesto a mi mamá, en moto prefiero andar

Aunque me deje el vestido roto y me golpee el poto

Papá, “con quien te acostarás que no sea mi mamá

Mientras ella en la cocina no se enterará”

Abuelita, si solterita me voy a quedar

A viejita no quiero llegar, sin saber lo que es el manjar

Y si mover la lengua quieren mis vecinas y mis tías que vengan a conmigo un día

Que a moverla mejor yo les puedo enseñar

Y si vagina no conocen mis amigas, sin dolores de barriga que me acompañen un día

Y conocerán hasta lo que es mandinga

Yo y mi chico nos cansamos, de que para besarnos y agarrarnos

El pantalón no podemos bajarnos ¡y hasta de miedo podemos cagarnos!

Yo sé lo que quiero, yo sé lo que quiero, yo sé lo que quiero,

no cuesta dinero y no da dolor ajeno.

Y eso a ti no te debe doler y si te duele, ¡Sóbate!