by Michelle Whiteley

A course website for Christina Laffin's students

by Michelle Whiteley

by Lillian Liu

Play the game at the following link!

https://prezi.com/view/P2gKLKp3m6nVN7sySKWN/

Commentary

The Confessions of Lady Nijo is a legendary woman’s diary written in the Kamakura period. It was a hidden secret until Yamagishi Tokuhei found it by a wonderful stroke of luck in the Imperial Household Library in 1940 (Brazell, 1973). The story starts with the life of a captivating courtesan and slowly evolves into the lady’s transformation into an independent female traveller through her “Buddhist awakening” (Laffin, 2005). It equips readers with abundant information to perceive and analyze the life of a woman inside and outside the ancient Japanese imperial court.

Because travel is at the heart of this literary work, the sugoroku game serves as an innovative medium to take the players on a highly evocative and spiritual journey with the protagonist. Through travelling, Nijo seeks personal repentance as well as spiritual redemption for her father, herself, and her past lovers, including the Retired Emperor GoFukakusa, and the deceased monk Ariake. The game mirrors Nijo’s happiness and losses experienced in life. Each of the selected events are critical building blocks that led Nijo to the person she grew into. Only through these ordeals and trials did she become the writer of such awe-inspiring literature.

This game not only connects us to the protagonist of the story, but also creates bonds between players. The game juxtaposes key moments and themes in Nijo’s journey, including solitude and community, romantic love and independence, luxury and asceticism, joy and grief. When players land on certain woodblock paintings, they can

click the painting and the image will magnify. As the photo magnify, instructions for players are revealed. Players will not get penalized for landing on the less fortunate stops. Each stop serves a purpose and offers a time for freedom in interpretation. Each round will be unique and has its own cadence as players offer different opinions and interpretations. By having players move through different paintings and explore diverse questions posed by each step, I hope players can find resonances with and derive a newfound understanding of this classic literary work. The questions and instructions in the game are meant to be open-ended so that players could ponder and articulate unique responses with each other. This in turn helps the sugoroku game become a vibrant hub for literary analysis and for players to bond with each other over a video conferencing platform.

One of my motives for creating this game in the midst of a raging pandemic is to transport players to a different world that is both reminiscent of player’s travel experience as well as a world that is completely novel. I hope that players can feel energized and hopeful through participating in Nijo’s journey and this sugoroku game.

Instructions

Please search for a “Random Number Generator” in your browser. Set the lowest value

to 0 and the largest value to 3. Each player will take turn pressing the number generator.

Enjoy the game!

Works Cited

Brazell, K. (1973). The confession of lady Towazugatari. Stanford, CA: Stanford

University Press.

Laffin, C. (2005). Woman, Travel, and Cultural Production in Kamakura Japan: A Socio-

Literary Analysis of Izayoi Nikki and Towazugatari. Columbia University.

Image Citations

Bunkyo, Sakuragawa. (1788). An Entertainment at Shinagawa [Woodblock print]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/36706.

Hokusai, K. (ca. 1830–32). Tama River in Musashi Province (Bushū Tamagawa), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjūrokkei) [Woodblock print]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/56392.

Hiroshige, U. (1817–58). Boat on the Sumida [Woodblock print]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/460337.

Hiroshige, U. (1857). Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge and Atake (Ōhashi Atake no yūdachi), from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo [Woodblock print]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/55433.

Hiroshige, U. (ca. 1840). Japanese White-eye and Titmouse on a Camellia Branch [Woodblock print]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/36722.

Hiroshige, U. (ca. 1834). Hiratsuka, Nawate Do [Woodblock print]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/55049.

Hokkei, T. (19th century). Woman in the Rain at Midnight Driving a Nail into a Tree to Invoke Evil on Her Unfaithful Lover [Woodblock print]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/54003.

Hiroshige, U. (ca. 1834). Yokkaichi, Sanchokawa [Woodblock print]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/36965.

by Leo Cheng

You are a wealthy merchant living in 1850s Japan. You have been a fan of Ando Hiroshige’s works and his work “53 Stations of Tokaido” has inspired you to travel along the Tokaido and visit Kyoto. As Japan opens to foreigners for trade and repaves the Tokaido, it has become more accessible than ever before so now would be the best time to go on your pilgrimage. As you have never travelled along the Tokaido before, your knowledge of the Tokaido is only based on Ando Hiroshige’s “53 Stations of the Tokaido,” so you have no idea what awaits you. You start saving up your ryo for the pilgrimage and think about what you could possibly encounter and the different people you will meet. You let your family know of your plans to go on this pilgrimage and initially you are hit with some disagreement as they warn you of the dangers of travelling alone. Also, they remind you that you need to save enough money for them as you are the primary income of the family. You reassure them that everything will be fine as long as you do not anger the daimyo or samurai that are also using the path and you also tell them that you have been saving up for a considerable amount of time and have more than enough to both embark on the pilgrimage and have enough to feed your family. After some consideration, your family hesitantly agrees, and you start getting ready for the pilgrimage. You start by heading into the market to find some food to bring along for your journey, you learn that along the way, the locals along the Tokaido provide food and cheap lodging for your journey. With the primary concern of food and lodging out of the way, you start to get ready for your pilgrimage. You go to a nearby temple to pray for good fortune and head home. The next day, you continue packing different sets of clothing for your journey and head out one last time to the markets of Edo. You buy some additional cloth for remuneration along the journey if needed and go home one last time. In the morning, with crystal clear skies, you look over at Mount Fuji and think to yourself, “I will see you up close soon.” You exchange goodbyes for your family for now and head out the shoji. With one ryo in your kimono and some extra food you have packed for the beginning of your journey, you head over to Nihonbashi where you will start your journey.

Bibliography

“Nagoya Castle, Home of the Owari Tokugawa Samurai: 昇龍道 SAMURAI Story.” Nagoya Castle, Home of the Owari Tokugawa Samurai | 昇龍道 SAMURAI Story, Central Japan Tourism Association, go-centraljapan.jp/route/samurai/en/spots/detail.html?id=20

Sekino, Junʼichirō, 1914-, Robert McClain, and University of Oregon. Museum of Art. The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō: Wood Block Prints. [Eugene, Or.]: Visual Arts Resources, Museum of Art, University of Oregon, 1978.

Crawcour, E. S., and Kozo Yamamura. “The Tokugawa Monetary System: 1787-1868.” Economic Development and Cultural Change, vol. 18, no. 4, 1970, pp. 489–518. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1152130. Accessed 7 Apr. 2021.

Hiroshige, Ando. “The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō Road.” Great Tōkaidō, Takenouchi Magohachi and Tsuruya Kiemon, www.hiroshige.org.uk/Tokaido_Series/Tokaido_Great.htm.

Hiroshige, Ando. “Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji.” 36 Views of Mount Fuji, Sanoki, www.hiroshige.org.uk/36_Views_Mount_Fuji/36_Views_Mount_Fuji.htm.

Schumacher, Mark. Guide to Japanese Pilgrims, Pilgrimages, Holy Mountains, Sacred Shrines, Mark Schumacher, www.onmarkproductions.com/html/pilgrimages-pilgrims-japan.html.

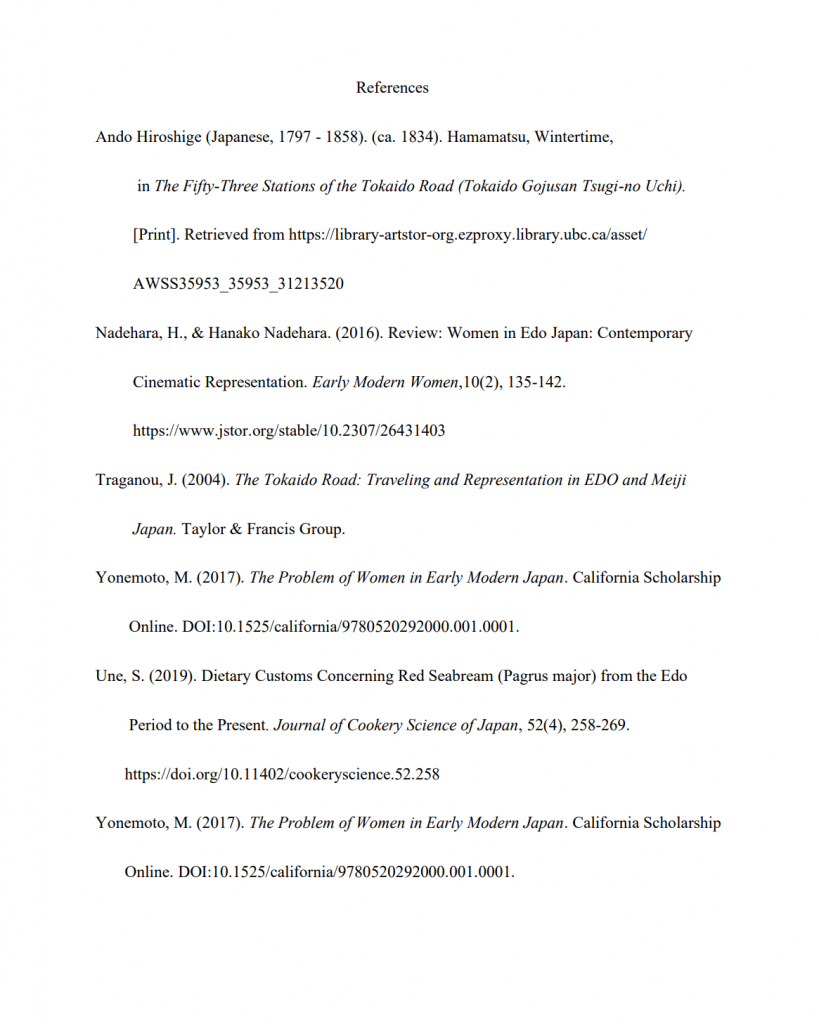

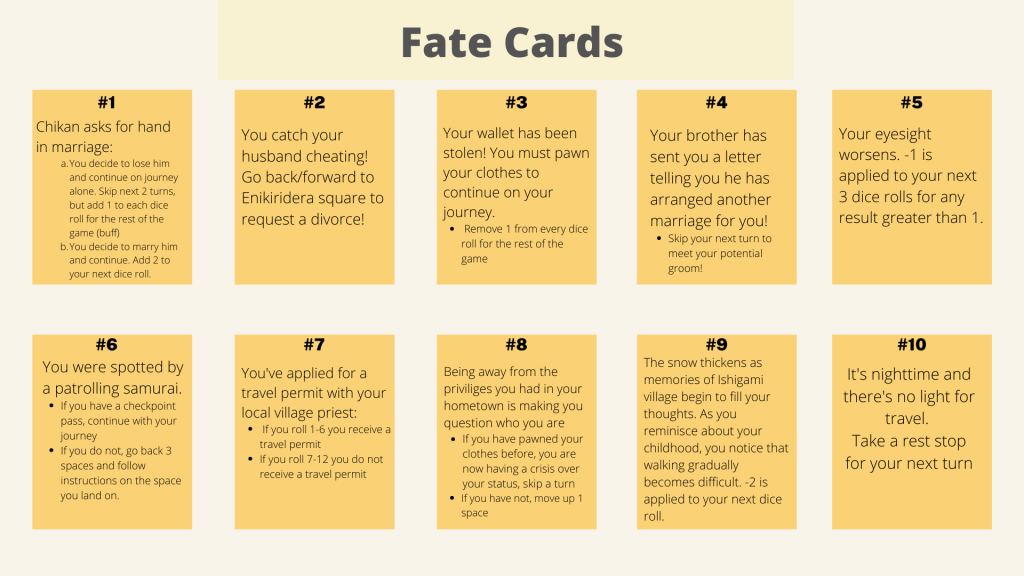

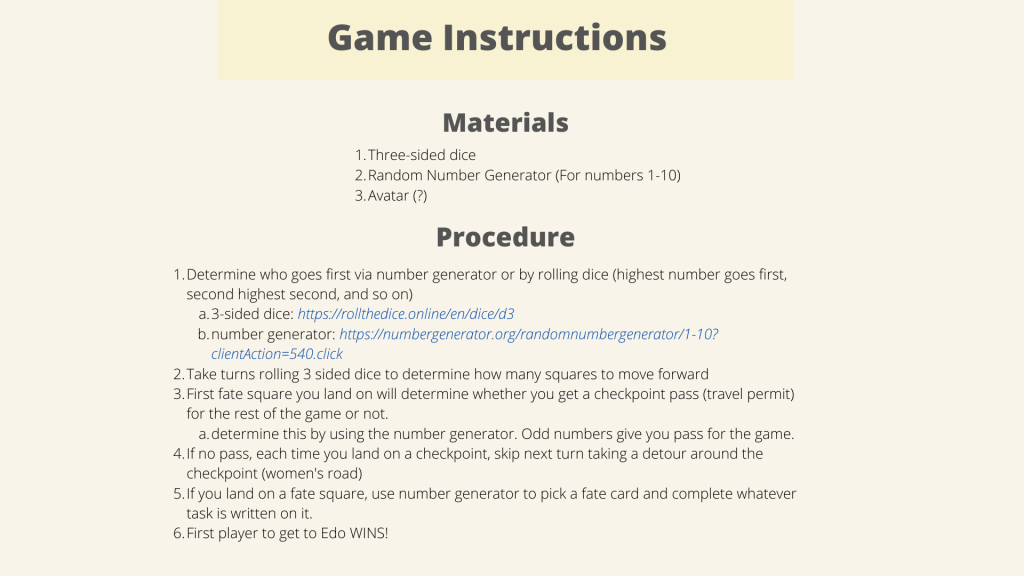

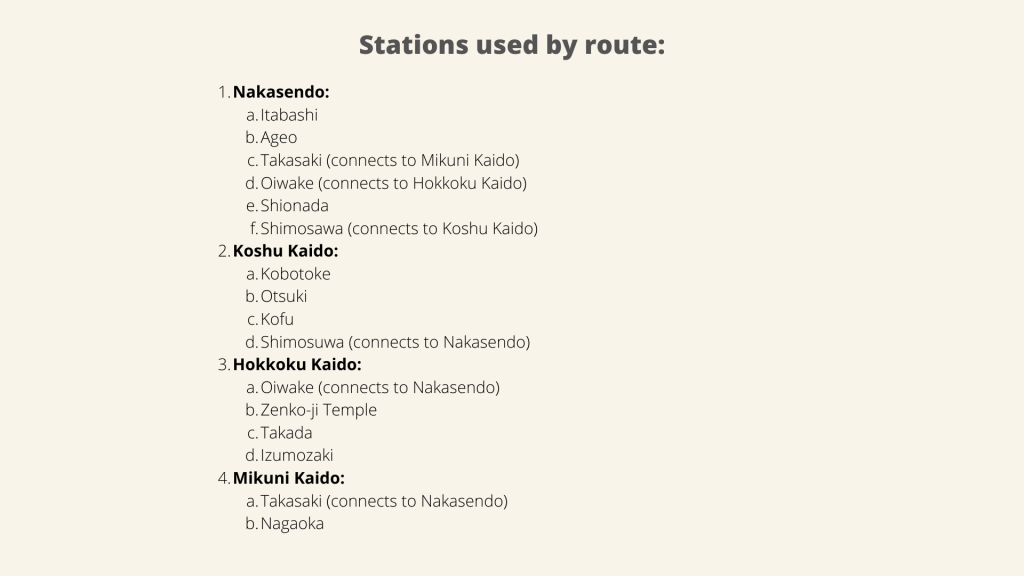

BACKGROUND

Tsuneno’s adventure begins in 19th century Japan where she explores the world unconventionally while going through hardships that include relationships, money and trying to achieve her goal of reaching Edo, which is a destination she had longed to visit. Over the duration of two weeks, she encountered treacherous mountain treks and situations that were difficult for her to dispute; she held a positive mindset and claimed that it was worth the journey. Tsuneno was someone that was crafty and always dealt with harsh circumstances the best way that she could during a time where “most ordinary women spent their lives working and breeding and, […] died at an early age, without having given any more thought to material independence or cultural enjoyments than to the possibility of visiting the moon” (Nenzi, p. 73).

Tsuneno’s story is one of uncertainty and brings readers through a plethora of emotions. Amy Stanley writes Tsuneno’s expedition in great detail, bringing the readers into her world and enabling them to picture the route and scenic sites that she discovers. This game will include the famous places that Tsuneno comes across and the experiences that she encounters.

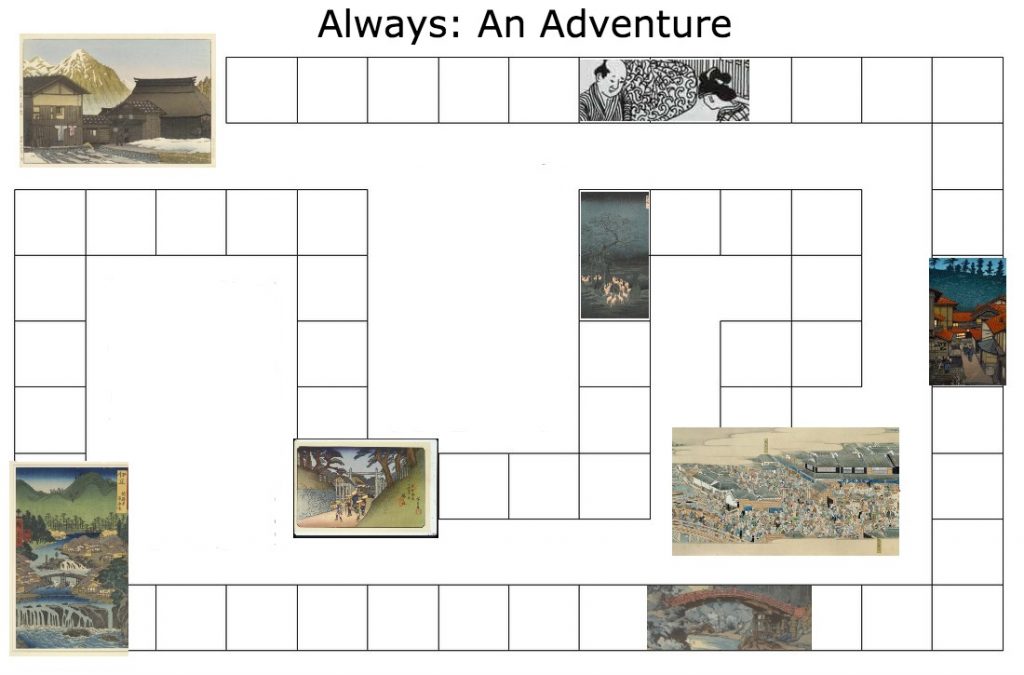

INSTRUCTIONS

The player will roll the dice and move forward the number shown on the dice. After rolling the dice, if the player stops at a blank space, no actions are needed, and the next player will go. If the player stops on a block with a picture, they must roll the dice again. If they roll a “4”, there is a consequence according to the image, and they must move back a spot. If they roll an “8,” they are rewarded and may move forward one spot. If they roll the dice and it is not any of those two numbers, the player stays in that spot.

dice link: https://www.teacherled.com/iresources/tools/dice/ (use two dice)

CONSEQUENCES

The first picture on the board represents the time Tsuneno arrives at Iimuro village, where she had to sell belongings from her trousseau to prepare for her journey, but “the value of clothing was unstable and difficult to measure” (Stanley, p. 176). If the player rolls an “8”, that means that the man showed interest in her items, and the player may move up a spot. If they roll a “4,” the man did not feel there was any value in what she was offering, and they must move back a spot.

The second image is when she sets off on foot to Takada, and the consequences vary depending on the number rolled. A “4” would mean that her brother sees her in Takada, and her journey is now delayed. An “8” means she successfully uses her trip as an excuse to start her journey to Edo.

The following picture is of the Shimogomachi bridge where she meets Chikan, who wants to go to Edo as well. If the player rolls and gets a “4,” that means that Tsuneno is unsure about continuing on the journey with Chikan and has to think about it for a few days, therefore, having to move back a spot, delaying the trip. If the player rolls an “8,” that means Tsuneno is excited to have a travel companion and does not need to spend money on an escort.

The image after the bridge is of Akakura, where Tsuneno stays a few nights to prepare for her journey. A “4” consequences in the player needing to rest for a bit and staying a few nights, delaying the journey further and therefore having to move back a spot. A reward would be that Tsuneno was brave enough to admit to her family that she is going to Edo, and because of her courage, she was able to move forward.

The next stop is at the Sekikawa Barrier, a checkpoint along the road where samurais check travel passes. Rolling a “4” means Tsuneno gets refused because she does not have the necessary documents. An “8” leads to her leaving the highway to avoid the checkpoint, thus being able to continue the journey but needing to hire a guide for a few dozen copper coins.

The stop after the Sekikawa barrier is the Hackberry tree, a “tie-cutting” tree with shrines beside it. A “4” would mean that she remembers the family that she has cut ties with and feels a bit emotional. Thus, the player must move back because Tsuneno ponders whether the sacrifices she had to make this far were worth it. If the player rolls an “8,” she reminisces and thinks about her family but sees it as motivation to continue her journey to finally archive happiness.

The last stop is Edo. Whoever reaches here first is the winner of the entire game!

SOURCES

Nenzi, Laura. Excursions in Identity: Travel and the Intersection of Place, Gender, and Status in Edo Japan. University of Hawai’i Press, 2008. muse.jhu.edu/book/8261.

Stanley, Amy. “Fashioning the Family: A Temple, a Daughter, and a Wardrobe.” Essay. In What Is a Family?: Answers from Early Modern Japan, edited by Mary Elizabeth Berry and Marcia Yonemoto, 174–94. University of California Press, 2019. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvr7fdd1.1.

———. Stranger in the Shogun’s City: A Japanese Woman and Her World. London: Scribner, 2020. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ubc/detail.action?docID=6235968.

Tianqi Chen

Game Commentary:

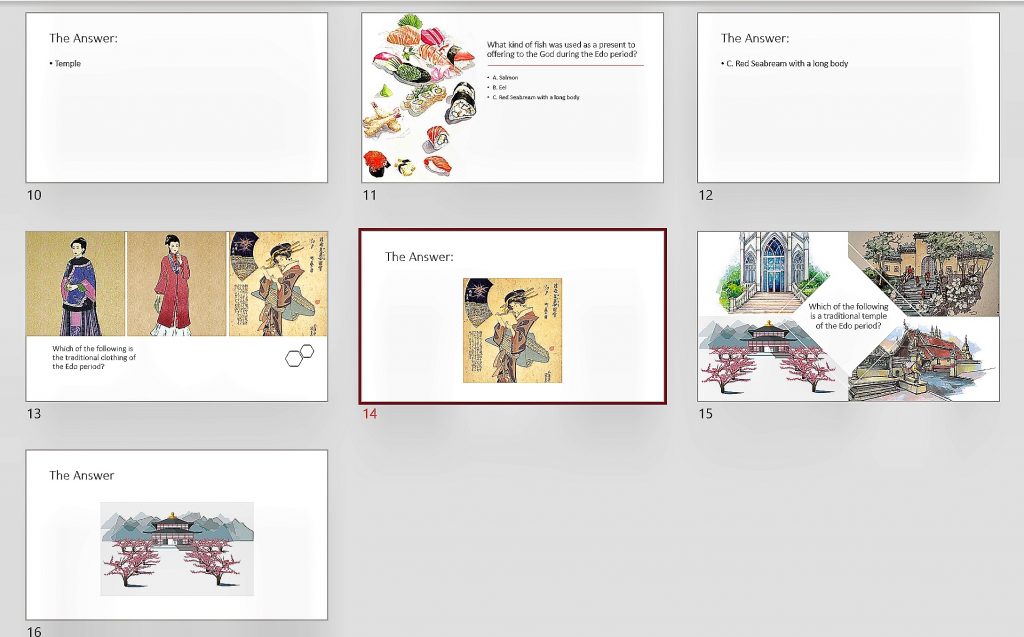

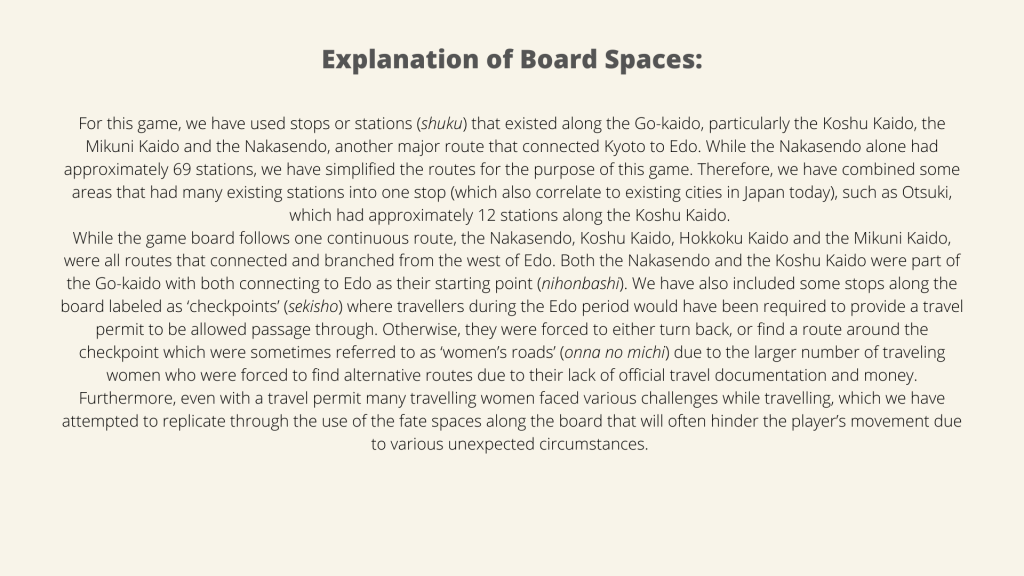

Filial piety, requiring respect, obedience, and care for one’s parents and elderly family members, was one of the most significant concepts of Confucian values, and a heavy influence on East Asia, including early modern Japan. The classic Confucian expectation of women’s filialness was raised in Liu Xiang’s Lienü Zhuan, emphasizing the highly idealized “exemplary woman” (lienü) as a model for behavior and comportment (Yonemoto, 2017). Within patriarchal Confucian society, the standard of the exemplary woman is based on her devotion to men, such as a husband, father, son, or teacher, and to family honor. Through sacrifices, women offer benefit to others, constituting one of their virtues (Yonemoto, 2017). In the Edo period, a woman’s filial piety was defined by serving her husband’s parents and bringing honor to her family through marriage. Ito Maki (1797–1862), was a commoner woman who was the eldest daughter of a prominent physician in Mimasaka Province. Her father, Kobayashi Reisuke, was a physician with a broad intellectual network and a student of Western science (Yonemoto, 2017). Maki received a good education and was able to express her filial piety and longing for her family of origin in her writing in later days. Maki’s family underwent various traumatic experiences, which profoundly influenced Maki’s life and created a filial bond of attachment between her and her parents. Maki was adopted by her childless uncle Kōzaemon, and she moved from Mimasaka to join her uncle’s family in Edo. Maki’s uncle Kōzaemon has higher social status than Maki’s father. He had acquired hatamoto status (Yonemoto, 2017).

Because marriage in the Edo period was about equal social status, through adopted by her uncle, Maki could raise her social status and marry into a better family, fostering a good reputation for her natal family. Therefore, this journey from Maki’s hometown Mimasaka to join her uncle’s family in Edo became a life-changing choice that would define the rest of her life. Based on historical evidence, Maki chose to be adopted by her uncle and married into a better family, thus fulfilling her duty of leaving a good reputation for her natal family. However, Maki also paid the price. She was not allowed to contact her original family at all, even though she missed them dearly. Maki could only express her filial piety to her parents by writing letters, and she once mentioned that she felt delighted when she saw the map of her hometown. Unfortunately, Maki never returned to her hometown for the rest of her life. She noted in her letter a desire to fly back to her hometown like a bird. Although women had very few choices in the Edo period, there were still some choices that women could make to escape the fate of marriage, such as serving in a wealthier home. Therefore, this map game adapts Ito Maki’s real-life story by giving her a second option to serve in a household of rank and to raise her stature and that of her natal family through hard work. Two routes are given to her as two different options: go to Kyoto and work, or go to her uncle’s house at Edo. These two routes both travel via the Tōkaidō highway, the most essential and convenient route during the Edo period, following the fifty-three post stations (limited here to six critical post stations).

Game Instructions:

Material and Procedure:

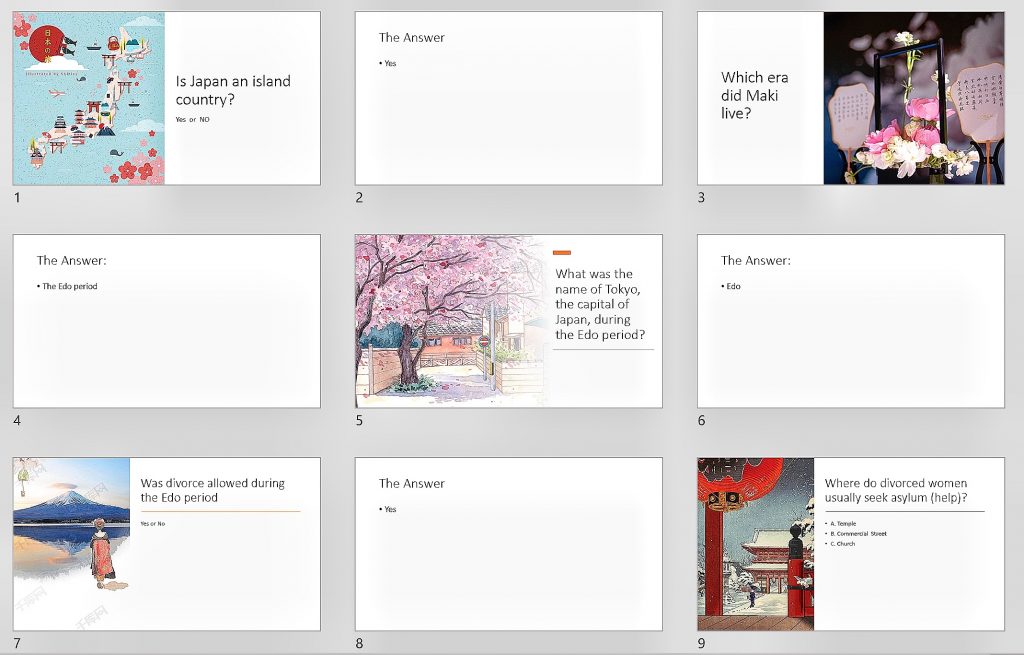

The question cards with answers:

Power point link to question cards:

https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/17BGoX9Zu06KoXmkvrkhSngXmKWHmRXkQ9

Vmq26ImVUw/edit#slide=id.p1

The Game Board:

The link of the dices:

https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1O5BAYfX4uRIYETumdkKtKCzHw84T_pR3Fu-3

O-fBiiw/edit#slide=id.gd3777506be_0_12

Andy, Anh, Shoni and Hiroshi

Click here for number generator

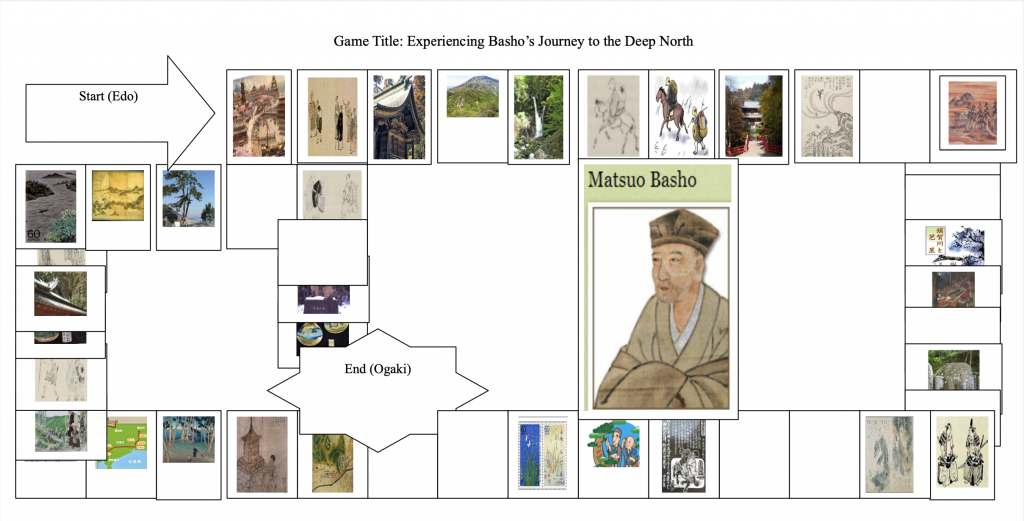

Matsuo Basho is one the most outstanding Japanese poets of haiku – a short form of Japanese poetry (Basho, 1996; Basho & Barnhill, 2005). He was born in 1644 in Ueno, Iga Province, to a low-ranking samurai family. Basho started writing poems as early as 1662. He was part of the Danrin School, where he participated in numerous competitions. He would later become a judge of poetry competitions and acquire students of his own, become a lay monk, and establish his own poetry school. Basho’s poems were influenced by his intimate relationships, especially with friends, as well as Zen and Chinese Daoism (Basho & Barnhill, 2005).

Feudal stability characterized the Tokugawa Period (1600-1868) (Basho & Barnhill, 2005; Downer, 1989). Hence, travelers could travel safely. Improvements in social mobility facilitated the widespread of arts and throughout Japan, regardless of class, with the merchant class taking on the arts. The Haikai no renga, a comic-linked verse, was significantly popular among samurai and merchants. This is how poetry reached Basho. However, in 1666, Basho’s friend Yoshitada died suddenly, making him consider leaving secular life. The flourishing arts made it possible for gifted writers to remove themselves from their daily life and become master poets. This is the path that Basho followed (Basho & Barnhill, 2005).

In the late spring (May) of 1689, Basho set off for a 2,000-kilometer journey from Edo (currently Tokyo) to the northern interior of Japan, as indicated in figure 1 (Basho & Barnhill, 2005). This journey happened to be among the last one, and it generated the infamous The Narrow Road to the Deep North (Oku no hosomichi). When starting, Basho admits feeling old and frail, but he felt compelled to make this journey. He dressed like a monk, carrying a wide-brimmed sedge hat and bamboo staff. As a lay monk, he owned nothing, relying on friends, disciples, and admirers (Downer, 1989).

Basho traveled for many reasons, including for religious and poetic purposes. At the time, traveling or wandering the countryside was viewed as an ascetic practice that helped shape and sharpen sacred visions and poetic creativity (Basho & Barnhill, 2005). Additionally, going on such journeys helped ascetics, monks, and poets remember those who had died before them and their legacy, as observed in Basho’s visits to monasteries and graves of famous people in his historical timeline. He also traveled to acquire more disciples (as he was a master in his own school) and spread his poetry throughout Japan.

It seems that to Basho, travel was more about the experience than the destination. From his poems, one can deduce that he walked to reflect and interact with people, nature, and culture. When leaving Edo, for example, he feels burdened by the goodbyes from family and friends. Although he is old and frail, he cannot leave these memories behind as a human being; it is his responsibility to carry the burden of sustaining relationships with friends and family rather than walk alone. Even so, he is propelled to keep moving on, whether through friends or to reach places, while never forgetting memories, and creating new friends, or finding new encounters at every turn (Kerkham, 2006). Therefore, this sugoroku is intended to be a game played with friends. As players experience Basho’s journey, they learn more about Japan and various essential aspects of the journey. Drawing from Basho’s poems, these experiences are worthy particularly because they represent the temporality of life.

Game Instructions:

Start point: (Edo)

End point: (Ogaki).

Number of players: 2-4.

All boxes, regardless of size and with or without visuals, hold equal importance. Note that only one player (the first to get to Ogaki) will be crowned Basho. The game ends when the first player finishes the game. If all players are unsuccessful in any of the steps, they stay in that stage until they are able to break through and continue their journeys.

The Shortest Way to Ogaki:

Roll numbers 1 and 3 when the game starts and jump past the Shirakawa Barrier (step 11). When successful, the player is allowed to cast the dice again. If the player gets dice number 1 or 6, they jump past the Great Gate at Date (to step 22). The player then rolls the dice again twice. Dice number 3 and 1 take the player past the Shitomae Barrier (Step 33). The player then casts the dice again. If they get dice number 2 or 5, it is game over as that skips them to Ogaki, the finishing line.

The Long Way to Ogaki:

References:

Basho, M. (1966). The Narrow road to the deep north, and other travel sketches (Vol. 185) (N. Yuasa, Trans.). Penguin.

Basho, M., & Barnhill, D. M. (2005). The narrow road to the deep north. In Basho’s journey: The literary prose of Matsuo Basho (D. M. Barnhill, Trans.). State University of New York Press.

Downer, L. (1989). On the narrow road to the deep north: Journey into a lost Japan. Vintage. Kerkham, E. (2006). Matsuo Basho’s poetic spaces: Exploring haikai intersections. Palgrave MacMillan.

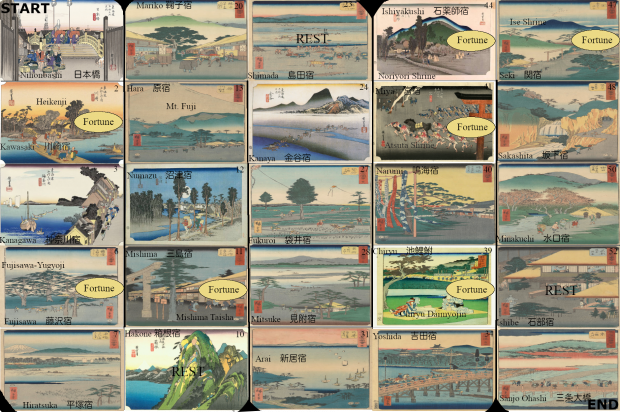

This board game is inspired by Edo period travel and the idea of famous spaces. Today, as tourists we often travel to see the sights and have specific foods we want to try and places we want to explore. Major temples are placed on the board game like Ise Shrine and Mishima Taisha. Other iconic places are mentioned in the good luck and bad luck spaces regarding food famous to the lands. High status women in the Edo period would often travel to shrines and temples to receive blessings or to regain some sense of independence. This factor was inspiration for the premise of the trip, women travelling with attendants and trying to explore and see the places they perhaps read about in novels or in poems.

Rules

Good Luck & Bad Luck

Good Luck

Bad Luck

Nihonbashi as a starting place felt to be key as it was seen as the center of Edo. Nihonbashi was positioned at a central crossroad for those entering and exciting the city. Its presence as a popular urban space grew in the late Tokugawa period and images of the bridge came to include people crossing and also the movement of goods into the city (Yonemoto, 1999). I thought this would be fitting to the start of this journey. Mount Fuji has been a point of cultural focus and seen as a sacred mountain for Japanese people. Climbing the mountain for religious enlightenment became popular during the Edo period (Sugimoto & Koike, 2015). It had been a place of worship from a distance and very revered by people in the city of Edo. Rather than going themselves, people would pay others to go in their stead and climb the mountain for their blessings. This religious pilgrimage is suggested as the roots for the modern travel to visit Mount Fuji (Matsui & Uda, 2015). Mitsuke-juku was a place known for its lodgings and restaurants. People would come from far away to have soba in Mitsuke before taking the ferry across the water. Atsuta Shrine close to Miya-juku is another important shrine for Japanese mythology. The shrine houses the sword of Susanoo no Mikoto, Amaterasu’s brother who is the god of storms. Atsuta Shrine is a cannot miss stop for those who wish to reminisce about Japan’s mythology, and it is an important stop right before Ise Shrine. Ise Shrine has been a very important religious place in Japanese history. Seki-juku is very close to the shrine and as this game’s main focus is to visit shrines along the Tokaido, I thought it would be a must-see place to visit for any traveler. The pilgrimage to Ise has been taken for centuries with poems written on the subject such as A Journey to Ise (1686). The Ise shrine is dedicated to the sun goddess Amaterasu among others. There were bustling tea stores, inns, and shops around the shrine in the Edo period that were thanks to the high pilgrimage culture at the time. Ise mandalas were placed at the shrine to show how to perform prayers for pilgrims and depict maps of the shrine area (Hardace, 2017). Sanjo Ohashi, like Nihonbashi in Edo, is another centre of cultural importance. Bridges as a symbol of connecting spaces and connecting people felt like the ideal end point for the journey. It was built in 1590, over the Kamo River which divides Kyoto in two. It held significance to Tokugawa Hideyoshi who had it built with stone pillars to replace the old, unreliable timber bridges (Stravos, 2014). It is an important landmark in Kyoto and a point of crossing to get to the other places of interest like the imperial palace or Nijo Castle.

References

Hardacre, H. (2017). Edo-period shrine life and shrine pilgrimage. Shinto: A History. Oxford University Press.

Matsui K., & Uda, T. (2015). Tourism and religion in the mount fuji area in the pre-modern era. Chigaku Zasshi, 124(6), 895-915.

Sugimoto, K., & Koike, T. (2015). Tourist behaviors in the region at the foot of mt. fuji: An analysis focusing on the effect of travel distance. Chigaku Zasshi, 124(6), 1015-1031

Stavros, M. G. (2014). Kyoto: An urban history of japan’s premodern capital. University of Hawaiʻi Press.

Yonemoto, M. (1999). Nihonbashi, edo’s contested center [ie centre]. East Asian History (Canberra), 17(17-18), 49-70.

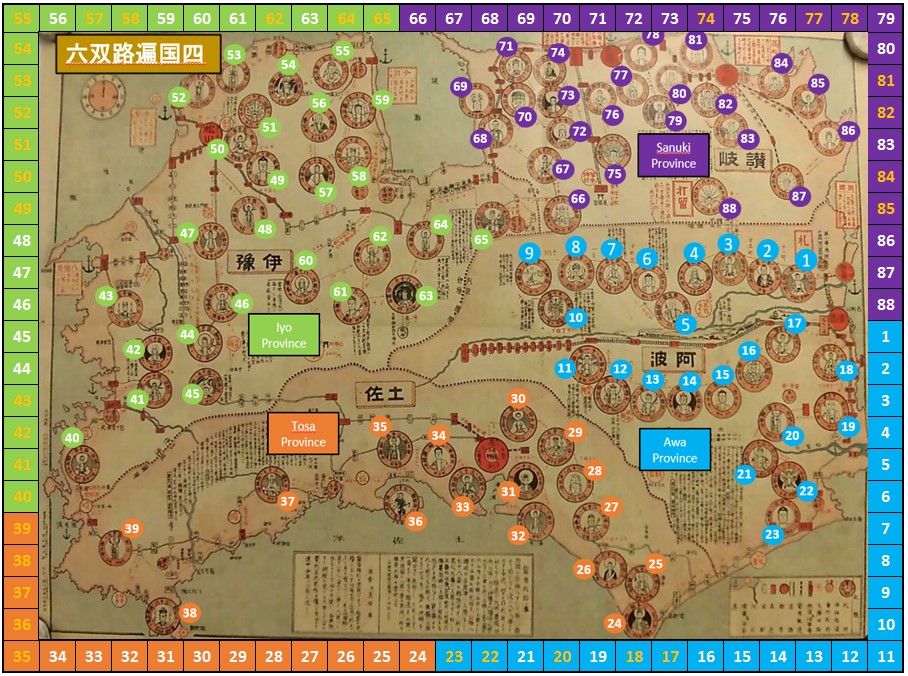

The Shikoku Pilgrimage

The Shikoku pilgrimage route dates back to the 9th century when the founder of the Shingon sect of Buddhism, Kōbō Daishi, established the route of the 88 temples that are spread across the four provinces of the island of Shikoku in western Japan. Ever since then, pilgrims all around Japan have traveled to Shikoku to follow his steps and complete the 1400 kilometers pilgrimage. Faith in Kōbō Daishi is central to the route. Pilgrims believe that the spirit of Kōbō Daishi travels along with them and his blessings can be received through the pilgrims themselves.

Although at first only priests and people in ascetic training would embark in the pilgrimage, it eventually became a popular route to complete among common people as well as its popularity increased and travel became more common in Japan especially in the late Edo period.

The 1918 Shikoku Pilgrimage of Takamure Itsue

In 1918, the 7th year of the Taisho Era, Takamure Itsue, a 24 year old woman from Kyushu embarked on a journey to complete the Shikoku pilgrimage around the 88 temples. She was motivated by a promise made by her mom that she would send her daughter on a pilgrimage if she had a daughter who grew up healthy as well as the desire to travel and get away from her personal troubles.

As an avid reader and write of literature, Itsue documented her journey from beginning to end through a series of articles that were published in the newspapers at the time. In total she wrote 105 articles which were later compiled and released as a book titled “Musume Junreiki.” Itsue describes in her writings the hardships of travelling across the route by foot at that time. The weather was a constant element that affected her travels as she often was affected by the rain. She was also often asked for her blessings for all kinds of afflictions from the locals. She describes her encounters with many pilgrims from different places around Japan, most of them over forty, most of them completing the pilgrimage in order to get help from Kōbō Daishi with their troubles and illnesses.

Like most pilgrims at that time, Takamure relied on support from the locals known as “settai” to complete her travel. When possible, Takamure would spend the nights at Inns but she often had to sleep outdoors due to the lack of money and failure in receiving free lodging. Begging was seen by pilgrims not only as necessary to survive and to complete the pilgrimage, but also as an ascetic practice and a part of Kōbō Daishi’s teachings. Yet, begging was actually illegal at the time and if caught, pilgrims would be kicked out from the province. A pilgrim told Itsue that the easiest provinces for begging were Iyo and Sanuki. She herself was faced by police when nearing completion of her journey.

It was not uncommon for pilgrims to die when trying to complete the route. Pilgrims would wear all white when completing the route, a color associated with death in Japan. Takamure often heard news of pilgrims dying as well as the graves of many along the route. At that time, the influenza pandemic was affecting the whole world, including Japan. It took Itsue over three months to complete the whole route to which she then returned home. Itsue herself contracted the flu shortly after completing her pilgrimage but luckily, she recovered from it and continued her way home.

Shikoku Henro Sugoroku

The Shikoku Pilgrimage Sugoroku game aims to replicate the hardships that a pilgrim like Itsue encountered while walking by foot through the 88 temples in early years of the Taisho era.

The goal of the game is to complete one lap around the Shikoku Island across the four provinces of Awa, Tosa, Iyo, and Sanuki. The goal of each pilgrim is to complete the Shikoku Pilgrimage route in order to visit all the 88 temples while facing the dangers of travelling by foot. Whichever pilgrim that completes the pilgrimage first would result in winning the game.

Movement

Players begin their journey in Temple number one and roll the dice to decide how many temples they can visit in their turn.

Weather and Events

Each turn the pilgrims will be affected by the weather and an event. These are decided randomly each turn and have different effects.

Begging and Lodging

Pilgrims start their journey with 40 Sen in their pockets. Each turn the pilgrims will do some begging and randomly receive some Sen or none in return. Begging while in Iyo or Sanuki province results in one additional Sen.

Pilgrims need to choose between spending 10 Sen to spend the night at an Inn at a nearby town (temples marked in yellow indicate when pilgrims can stay at an inn) or to spend the night camping outside at no cost. The movements of the pilgrims will be affected whether they spend the night at an Inn or Outdoors.

Additional Ways of Winning and Losing the game

A pilgrim can immediately lose the game if affected by a “Death” event 4 times in total.

A pilgrim can immediately win the game if affected by a “Encounter with Kobo Daishi” event 8 times in total.

References