… And with our “final cut” finally done, I am extremely relieved yet somehow unsatisfied with the version we have handed in. Now that I have been through the whole process of creating a documentary, I can honestly say that the blood, sweat, and tears behind the production of our film was worth it, mainly because I had so much fun with my group mates (I swear we work when we’re together and not just eat! though twitter might show otherwise). Despite our group being the largest with 4 members, I felt like it was the perfect number to have. Everyone had their roles–– sound (Kaitlyn), main interview camera (Kathy), b-roll camera (Mimi), interviewer (me; excluding Vietnamese interviewees). As we proceeded with our 6 interviewees, we all fell into a rhythm of our own. It was a familiar yet exciting routine that I looked forward to every time, as I would anticipate what would happen when we asked our questions, what would be said, what sort of fun would we have while filming. As the important thing is the journey and not the destination, I would say I thoroughly enjoyed my journey as a member of my group, and as a short-term film student.

Through the course of these past three months, I have condensed a list of things I have learned while being in #ACAM350.

9 Things I learned from ACAM350, 1 Thing I didn’t (not limited to the classroom):

- Editing sucks the life out of you.

- B-roll is random but is also not; you need to know what you need, but sometimes what you don’t think you need can become what you need.

- Translating is never really truly accurate.

- Patience is a virtue that will escape you––trying to find music and syncing the film to it will have you ready to give up.

- Interviewee’s opinions are important but ummm… uh…… sometimes it’s not relevant and we need to be ruthless.

- There are way too many files and content that naming becomes super important yet super random.

- I have FLAGGED1.prproj to FLAGGED8.prproj saved on my harddrive; premier autosave saves lives.

- Audio consistency and levels makes a big difference.

- Documentary film making is not as easy as it looks.

- Setting up lighting was like trying to wrestle with wires and frames.

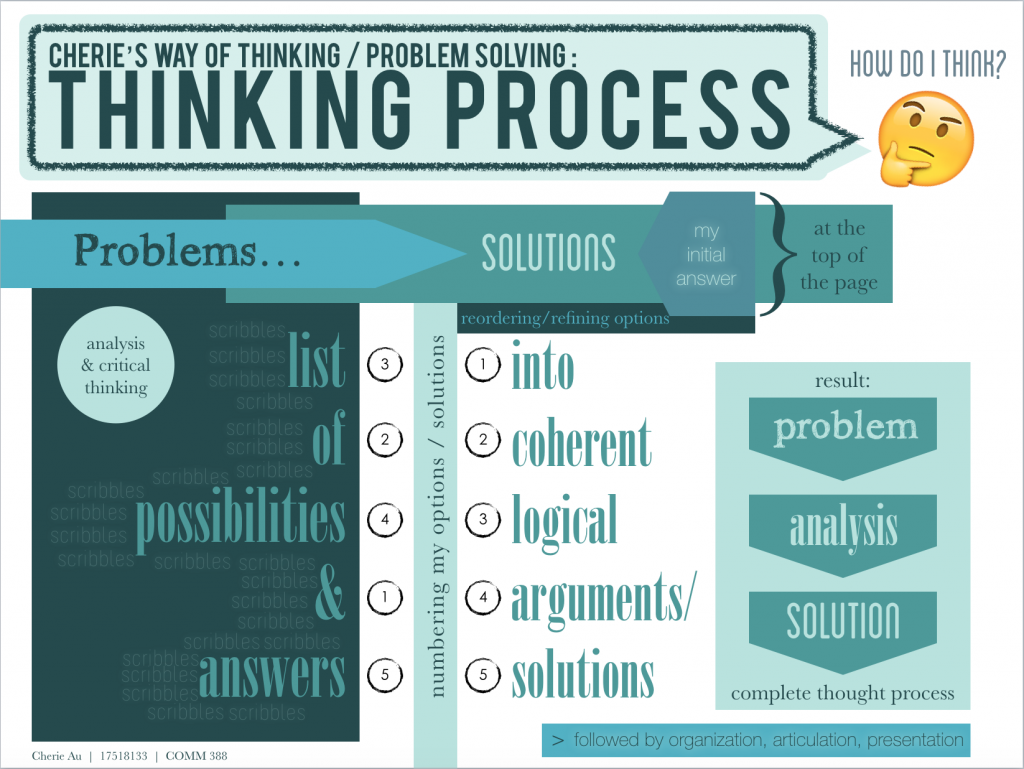

The technical process of setting up pre-interviews, filming the interview, logging, editing, cutting, music hunting, audio tuning, b-roll filming… That wasn’t as difficult as the creative process. From brainstorming to proposal writing, then interview question making, constructing the narrative, cutting out stories, re-constructing the narrative; all of these took way more time and effort, and gave me an insight into the kind of thinking and analyzing that goes into creating a film. The nuances and the little details of each segment is broken down and analyzed by us to try and understand the film we want to create. There were many times when we would be debating about keeping or cutting a certain part, each of us having their own reasons for their decisions. The dialogues that we had regarding the impact of the interviewee’s voice, to the meaning of their words sparked interesting conversations about our own narrative direction and what we wanted to say with the film.

The learning I have done through interacting and speaking with our interviewees as well as my group members has made me aware of issues I didn’t know existed before. Looking back, my school just did the bare minimum of educating us about history, but what can you do. The struggles and the pain and hurt that our interviewees carry over from Vietnam or from their parents linger within them, and how each of them chooses to express that becomes a personal story about the Vietnamese. Sadly, because of the topic of our film we couldn’t delve deeper into a single person’s story. The use of the yellow flag is controversial because of what it represents, whether it be the “lost” Vietnam, or “Freedom and Heritage”. Our video only brushes the surface of the topic and what the flag represents to the different Vietnamese people in Vancouver. With each interview, I learned more about a history I have never come across, and through the creation of this video have become connected––to people, to history, to culture. And not just the Vietnamese, but also to Canada.

Canada has a reputation for being a nice place, somewhere you can go to for better opportunities, somewhere that’s nice to live. I found this motif to be recurring with a lot of our interviewees; and that really speaks to the kind of place Canada is, and to what Canada as a country has to offer to Canadians, whether they be immigrants or first/second/n-th generation. The conversations about being Canadian and living in Canada made me question what being Canadian means to me, and what do I see Canada as, whether its a country of opportunities, of open discourse, of community, or of beautiful natural scenery.

All in all, the film has become a way for me to learn not only about Vietnamese history, but also of the conversations around being Canadian. The technical skills are definitely something that will be helpful in the future, but the dialogues we have had and the stories we’ve shared are ones that I will continue to think about and investigate. I really look forward to the screening, to see how everyone’s films turned out! Thank you for an enjoyable class, and keep creating #ACAM350! (: