It’s no secret that global warming, a consequence of human industrialization, has negative impacts on both humans and animals. When trying to connect global warming and animals, many people instinctively think of the popular image of a lone polar bear desperately trying to survive on a tiny block of ice. However, extremes like this are only a small part of the big picture. In reality, many animals are impacted in a much more subtle, but still very important, manner.

Polar Bear on Ice; Source: https://sites.google.com/a/d303.org/harry–endangered-polar-bears/global-warming-and-climate-change

Who:

Benjamin Freeman, an evolutionary ecologist doing research at the University of British Columbia, is an expert in his field who is exploring these more subtle impacts. His research program often focuses on how global climate change impacts biodiversity, which is explored in one of his recent studies “Expanding, shifting and shrinking: The impact of global warming on species’ elevational distributions”. This study was done by Benjamin and three other researchers: Julia Lee-Yaw, Jennifer Sunday and Anna Hargreaves. Before getting into the details of the study, lets first learn a little more about Benjamin and his motivations.

Overview of the research:

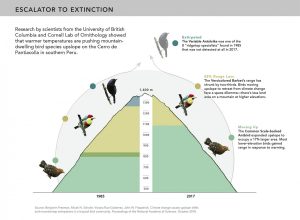

In the study, Benjamin and his team of researchers analyze how three types of species: lowland, unconstrained(species living in the middle of the mountain) and mountaintop species, shift their habitats as temperature changes. The basic idea is that species on a mountain have a warm and a cool range limit. The cool range limit is the coldest temperature that the species can survive in, while the warm range limit is the hottest temperature the species can survive in. Since the study focuses on species living in mountains, the cool limit correlates to the highest elevation and the warm limit to the lowest elevation. They hypothesized that cool range limits would be more sensitive to temperature change and thus moved upslope faster than warm range limits.

Methods:

The major taxa that Freeman and his group studied are vascular plants, endotherms, and ectotherms. They measured the cool and warm range limits for 975 different species from 32 different elevational gradients.

Statistically, they used the Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GLMM) in order to understand the amount that a species moved up or down. In this study, some animals moved up, some moved down, and some didn’t move at all. This statistical model helps explain something that is observed given something that you think is important.

Results — What will happen in the upcoming future?

The results in the study, didn’t show any significant difference between the shift in cool and warm limits. Yet there are some other crucial findings in terms of the elevational distribution of the lowland, unconstrained and mountaintop species.

Mountain birds on an ‘escalator to extinction’; Source: http://news.cornell.edu/stories/2018/10/survey-mountain-birds-escalator-extinction

Freeman thinks that in general species are shifting up towards the top of the mountain as temperature rises. Their findings indicate a broader domain of species shifting from equatorial regions towards the poles in order to run away from the warming temperatures near the equator. Freeman states that,

“I do think that for most species, the mountains will be tall enough so that they can keep moving up higher and higher. My prediction is that we may see some of these extinctions, especially in the tropics. But most temperate zone species, even if they live in the mountaintop, they might disappear from that specific mountaintop but they’ll still live on different mountains in British Columbia.”

But he also brought up a phrase called “the escalator to extinction”, which means that as temperature rises, species will continue to move up until one day there is no more mountain terrain to climb, leading to their extinction.

Here’s a short video on species’ range shift and global warming in a bigger picture, and Dr. Benjamin Freeman’s thoughts on how they are affecting animals and humans:

We would like to thank Dr. Benjamin Freeman for his time and Dr. Vishakha Monga, our instructor, for giving helpful advice on our project.

By Group 4: Jasleen Jassal, Leqi(Nancy) Wan, Elvis Kuan, and Trevor Shen