This is the first post in a new series from the course “Topics in the History of Education: Histories Confronting White Supremacy,” led by Professor Mona Gleason.

This course delves into colonialization, racism, and systemic oppression, exploring how historical understanding shapes our world today. In this series, students collaborated to craft blog posts where they explore themes related to course topics and share their insights with the larger EDST audience.

Keep an eye out for more posts in this series!

Co-authored by Aneet Kahlon, Erin Villaronga Mulligan, and Mark McLean, this blog post discusses the complexities of historical narratives surrounding education and white supremacy. Drawing insights from the work of Michael Marker and other course readings, the authors reflect on topics like colonial borders, Indigenous experiences, and educational structures.

Co-authored by Aneet Kahlon, Erin Villaronga Mulligan, and Mark McLean, this blog post discusses the complexities of historical narratives surrounding education and white supremacy. Drawing insights from the work of Michael Marker and other course readings, the authors reflect on topics like colonial borders, Indigenous experiences, and educational structures.

In this post, we centered our discussion on the work of Michael Marker, an Arapaho scholar, whose invaluable contributions have not only left an enduring impact on the EDST community but have also significantly influenced scholarship in higher education (Gill et al., 2023).

Within our conversations we weave together our understandings of his work with other readings that we have been offered throughout our course to answer the question:

ANEET: In other classes, we’ve talked about how borders are arbitrary concepts, but Michael Marker’s (2015) article, “Borders and Borderless Coast Salish: Decolonizing Historiographies of Indigenous Schooling,” made me think about this idea within the context of B.C.

It’s new for me to think about how Canadian residential schools and American boarding schools affected a single community differently depending on what side of the border they were on. It reminded me about the partition of India and Pakistan, where connected communities were forced to migrate to a specific side of a border randomly drawn up by a white man. I also think about my research because focusing on B.C. educational policies is a constraint that’s inherently colonizing. Indigenous communities don’t end at the border just because my analysis does.

MARK: I’m thinking about how many times Marker walks up to an idea and then shows that it’s too complex to follow in a short article, and instead notes another author in that space. These threads are worth pulling, and need to be pulled, and that makes the idea more complex.

ANEET: It’s been helpful to complicate ideas in this class!

MARK: When I read Marker’s work, I connected it back to a chapter of Thomas King’s (2012) book The Inconvenient Indian that we read; they both serve as a call to complicate things and acknowledge their complexity. As opposed to a flattened perspective, just on one side of the border. There is a quote in King’s work that says, “North America hates the Legal Indian. Savagely. The Legal Indian was one of those errors in judgment that North America made and has been trying to correct for the past 150 years” (King, 2012, p. 69). Each country wants to have a story to tell about what is going on with Indigenous peoples, Indigenous existence, and epistemologies, but all ignore complexity. In the U.S. it was public schools where Indigenous students experienced more racism, whereas Marker suggests that boarding schools were places where Indigenous students could also connect and define their own identity. This made me think about identity and what King (2012) called the “Dead Indian,” because as a nation, we’re not seeking out these complexities.

ERIN: Having done my undergraduate work at a U.S. institution, I guess I’ve never tried to fully articulate the experience of studying structural racism of public schools and educational inequality in an American context to learning about movements of indigenizing or decolonizing public schools in British Columbia. Because of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action, I think many people are so focused on the historical aspect of residential schools, and not as much on the broader racist and colonial structures of modern public schooling systems. This is a complete flip in perspective for me; something that I’m processing as I talk through it now.

MARK: Yeah! Both articles speak to the idea of treating residential schools like they only existed in the past. And Canadians love a chance to forgive ourselves. We’re less concerned with the transition out of residential school systems, and how much racism and damage happened in that situation. Everything didn’t just end when the last residential school closed. Again, it’s just flattening a narrative.

When we talked about the Boldt Decision and how the judge decided on fishing rights for Indigenous peoples in America, it reminded me of the CBC article talking about the Mi’kmaq lobster disputes in Nova Scotia. Canadian media didn’t know how to approach what was basically terrorism by white fisherman. So much of this results from an educational system where we’ve been taught this flat story, flat story, flat story. How different would it be if there was an understanding of the complexity of all this, for the Mi’kmaq and for our case, the Coast Salish?

ERIN: I want to shout out a different article from one of Mona’s classes. It’s “‘The children show unmistakable signs of Indian blood’: Indigenous children attending public schools in British Columbia, 1872-1925” by Sean Carleton (2021). He writes about the history of Indigenous children that attended public schools in British Columbia. It was an interesting read for me not having known a lot about how public schools were established here. The stories of those children and the adults (Indigenous and settler) that facilitated their enrollment in those public schools added another dimension to that normally flat story you’re talking about, Mark. The histories of white supremacy and those fighting against it in the world of education don’t all follow the singular residential school narrative that gets told.

ANEET: Mark, you’ve made a good point! What we learn about through Canadian education systems must fit within the constraints of what Eurocentric values want us to learn. For example, social studies curriculum teaches “Canadian” or “B.C.’s” history. A bordered history. These constraints act as a mechanism of validating those imaginary borders.

MARK: Yeah! I keep thinking, Aneet, about your comment about the border in Punjab, and how people had to swap back and forth across the border. I just googled the Salish Sea because I never think about it as a unit in the same way that we think about the Mediterranean as a unit. It’s so hard to untangle… yeah, it’s just really hard to not see borders.

ERIN: And all our other units of geographical organization. Water borders have always been especially bizarre to me. Because water is water! You just can’t draw a border in water! And that really emphasizes another idea that I think Marker brings us face to face with within this article: about how settlers conceptualize not only land, but place.

Place-based education is big, especially in early childhood right now, with things like forest schools, but we need to be careful about what type of teaching is still reinscribing very particular understandings of place that don’t align with the original stewards of this land. I don’t know if it’s possible to reach the same understanding. But if we’re taking children out for nature walks and talking about street names and showing them “borders” of parks and such, it’s almost like, what’s the point?

MARK: Totally! This connects well to “Decolonization is not a metaphor” by Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang:

“These fantasies can mean the adoption of Indigenous practices and knowledge, but more, refer to those narratives in the settler colonial imagination in which the Native (understanding that he is becoming extinct) hands over his land, his claim to the land, his very Indian-ness to the settler for safe-keeping. This is a fantasy that is invested in a settler futurity and dependent on the foreclosure of an Indigenous futurity.”

Essentially, when settlers adopt watered-down practices of place-based learning, its main purpose is to reinforce a safe settler future.

We went for a walk in Musqueam territory for Pro-D day and they pointed out Iona Beach Regional Park across the river and showed us that it didn’t count as their territory. Musqueam has fishing rights, but they’re hampered by the actions of the logging industry across the river. I imagined these lines across the water and it’s an absurd, imposing, and abstract idea. It’s just a river.

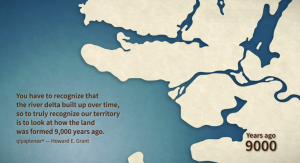

I wanted to share this map with you. Musqueam collaborates with the Museum of Anthropology, and they have a map that shows how the delta formed over 10,000 years ago. It made me think… MAN! Richmond didn’t exist 10,000 years ago. Indigenous peoples were here before Richmond existed as a physical land. Not only are these lines arbitrary, they’re also shifting!

References:

- Carleton, S. (2021). “The children show unmistakable signs of Indian blood’: Indigenous children attending public schools in British Columbia, 1872-1925,” History of Education, 50(3), 313-337.

- Gill, H., Kelly, D. M., Martin, K. S., & Mazawi, A. E. (2023). “Editorial Introduction, Indigenous Historiographies, Place, and Memory in Decolonizing Educational Research, Policy, and Pedagogic Praxis: Special Issue in Honour and Memory of Professor Michael Marker (1951-2021),” Journal of Contemporary Issues in Education, 18(2), 1-7.

- Grant, T. (October 14, 2020), “Vehicle torched, lobster pounds storing Mi’kmaw catches trashed during night of unrest in N.S.,” CBC News.

- King, T. (2012). “Chapter 3: Too Heavy to Lift,” in, The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America (pp. 53-75). Random House.

- Marker, M. (2015). Borders and the Borderless Coast Salish: Decolonising Historiographies of Indigenous Schooling. History of Education, 44(4), 480-502.

- Museum of Anthropology. (n.d.) Musqueam Teaching Kit.

- Tuck, E. and K. Wayne Yang. (2012). “Decolonization is not a metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, and Society 1(1), 1-40.

Share

Share