Just uploaded Meta-Analysis, the latest in a book I’m working on titled Methods of Analysis. It’s basically a side project or backstory to a few other research projects. Download the essays or working chapters from https://blogs.ubc.ca/researchmethods/methodologies/analysis/

-

Recent Posts

Recent Comments

- Stephen Petrina on #Unbelievable: experts and common sense

- Belinda on #Unbelievable: experts and common sense

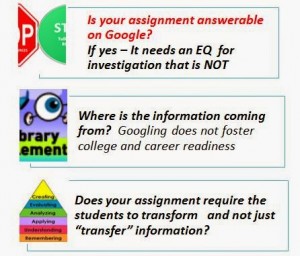

- Rachel A. on Is Googling Research?

- Helen Ballam on Getting inside people’s heads via ethnographic and phenomenological interviews

- Jeena on Getting inside people’s heads via ethnographic and phenomenological interviews

Archives

Categories

Meta

Recent Comments

- Stephen Petrina on #Unbelievable: experts and common sense

- Belinda on #Unbelievable: experts and common sense

- Rachel A. on Is Googling Research?

- Helen Ballam on Getting inside people’s heads via ethnographic and phenomenological interviews

- Jeena on Getting inside people’s heads via ethnographic and phenomenological interviews

Tags

Meta

Authors

Follow

Follow