Global decline in enrolments is real (data below) but does it reflect a declining societal need for geoscience expertise? If the need is not declining why is enrolment declining?

NOTE: much of this page refers to “geoscience” because extracting similar information restricted to quantitative geosciences seems difficult or impossible.

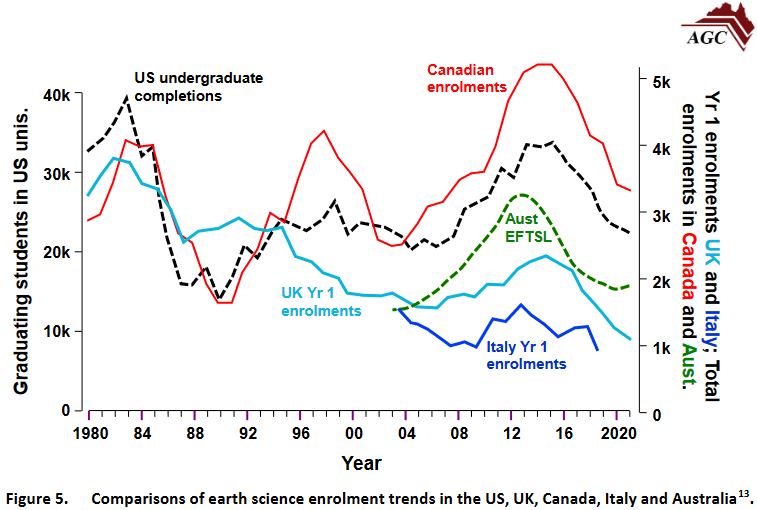

Five countries: The recent Australian Geoscience Council (AGC) report on tertiary geoscience education by Cohen, 2022 provides a global perspective by comparing geoscience enrolments in Canada, USA, Australia, UK, and Italy (figure below). There seems to be a slight increase in geoscience enrolments only in Australia starting in 2020, while all other jurisdictions saw continued (although possibly slowing) decline.

(The extensive AGC report also comments on “Content and curriculum”, “Post graduate degrees and micro credentials” and suggests these three aspects represent opportunities for increased collaboration between industry and academe. The report also discusses changes in staffing, geosciences in K-12, and recruiting.)

The decline in geoscience enrolments continues in the USA into 2021, based on AGI’s Status of Recent Geoscience Graduates, 2021, pg 10.

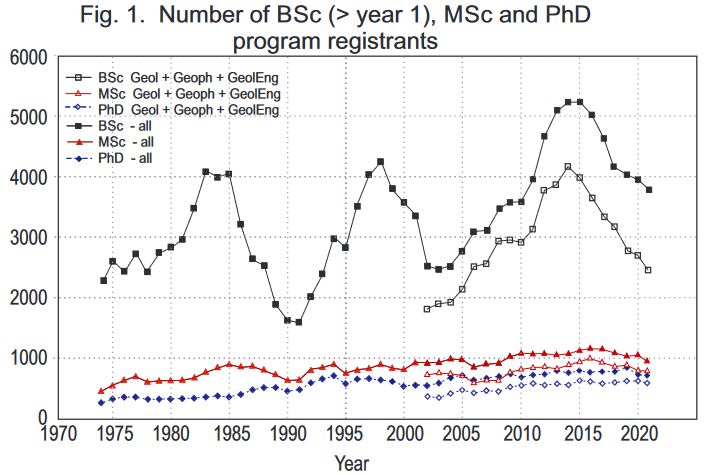

Canada: from conversations with peers, and from CCCESD data fro 1975 – 2021 it is evident that undergraduate enrolments in bachelors level programs across Canada continue to decline. Between 2000 and 2022 the number of faculty in Earth Science departments across Canada increased from ~500 to ~600 (figure 5 in CCCESD’s data summary sheet).

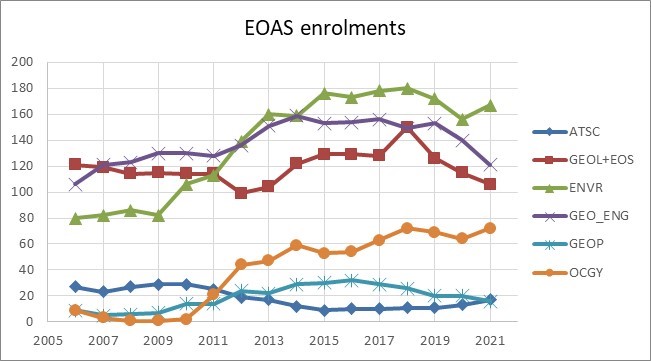

EOAS: Do UBC’s enrolments in EOAS degrees reflect this national trend? Yes, to some extent (next figure), but only for engineering, geology plus EOS and Geophysics, but not for oceanography (which includes biological ocgy), environmental sciences and atmospheric sciences which are all are experiencing increasing enrolments. For further enrolment and related data, see data from 2020 presented here. More specifically, enrolments have shrunk significantly in geophysics (32 students across all years in 2015 to 20 students in 2021) and atmospheric sciences (29 students in 2011 to 10 students in 2021) while oceanography & physics has always had small student numbers (~ 2) (Schoof, 2021).

Why this global decline in geoscience enrolments? Quantitative geoscience graduates can be hired into many sectors in Canada. It is hard to aggregate information about global or national demand from all sectors, but especially in Canada and Australia, data related to resource exploration may provide some insight.

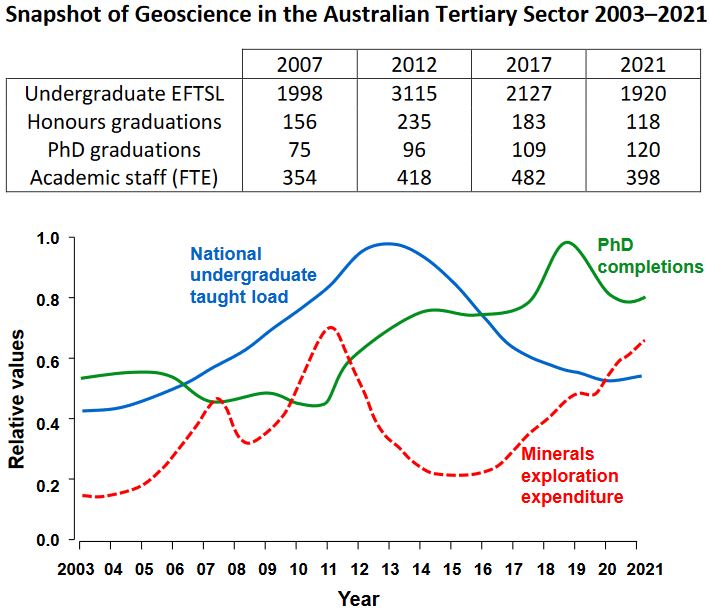

In Australia, the growth in mineral exploration expenditure may be contributing to an emerging increased interest in geoscience degrees. Cohen’s AGC report presents data showing a lag of 5 years between the most recent trough in exploration spending and the most recent troughs in geoscience enrolments and PhD completions.

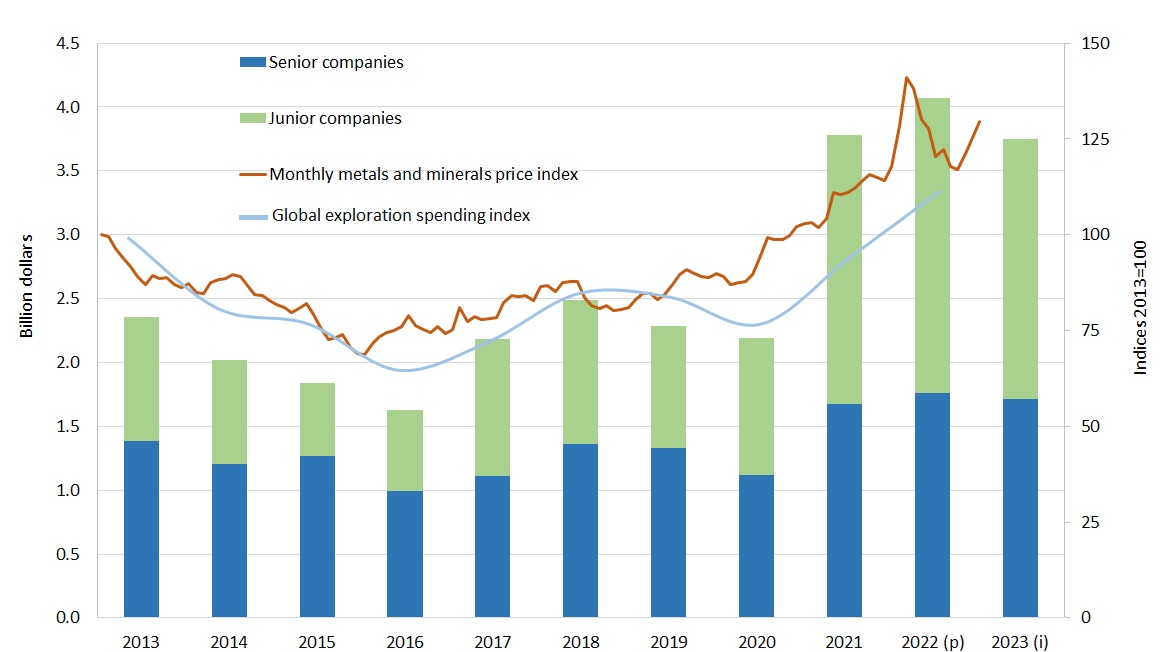

Analogous data for Canada from the Canadian Mineral Exploration Information Bulletin (June 2023) suggests that the pattern of exploration spending in Canada (minerals, not oil/gas) was also lowest between 2015 and 2016, but the subsequent increase does not seem to be as uniform as in Australia (bars on the following graph).

Meanwhile, expenditures on geology and geophysics for oil and gas exploration in Canada have reached their lowest levels since 1977 (from data at the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers or CAPP).

There may be a relationship in Australia between exploration industry spending and geoscience enrolments, albeit with a 5-yr lag, yet in Canada the picture seems more complicated. Canadian mineral exploration activity seems relatively strong in the past 2-3 years but oil & gas exploration activity that involves geology or geophysics remains slow. Meanwhile, geoscience enrolments across Canada continue to decline, while at UBC, enrolments in resource-related geosciences have declined recently (although apparently not as rapidly as national averages), while other disciplines taught in EOAS appear to be seeing increased enrolments.