In his article “A Curriculum for the Future”, Gunther Kress writes that a radical shift in thinking and curriculum in ELA classrooms is due to occur in response to the different needs of the contemporary adult in 21st century society. He states that the world has changed so much that the 19th century model of education is just not applicable anymore. Kress calls for a shift in curriculum from an education for stability to one for instability:

“Associated with this are the new media of communication and, in particular, a shift (parallelling all those already discussed) from the era of mass communication to the era of individuated communication, a shift from unidirectional communication, from a powerful source at the centre to the mass, to multidirectional communication from many directions/locations, a shift from the ‘passive audience’ (however ideological that notion had always been) to the interactive audience. All these have direct and profound consequences on the plausible and the necessary forms of education for now and for the near future.” (138)

The notion of a multi-directional communication and a shift to an interactive audience is what stands out for me in Kress’ assertion. As such, I have designed an activity for use in an ELA classroom that allows students to be creators and participators in such a communication. Using a variety of online tools, students are able to work collaboratively to create a co-authored product. The product can be inspired by whatever you are currently studying in your class—it could have a thematic or topical connection to a literary text, or it could simply be a pre-writing exercise begun with a prompt. The only stipulation is that the activity be carried out in silence thus disturbing the notion of passivity and activity, telecommunication and proximity, and the product of the individual vs. that of the group. So far in this class we have explored the following topics:

• modes of representation in ELA classroom/21st century literacy

• visual literacy and rhetoric

• media literacy

• social media and the notion of participation

• new literary forms/e-literature

• computer mediated communication

• gaming

I also designed this activity to address pieces of all of the things we have discussed thus far in regards to these topics.

Activity:

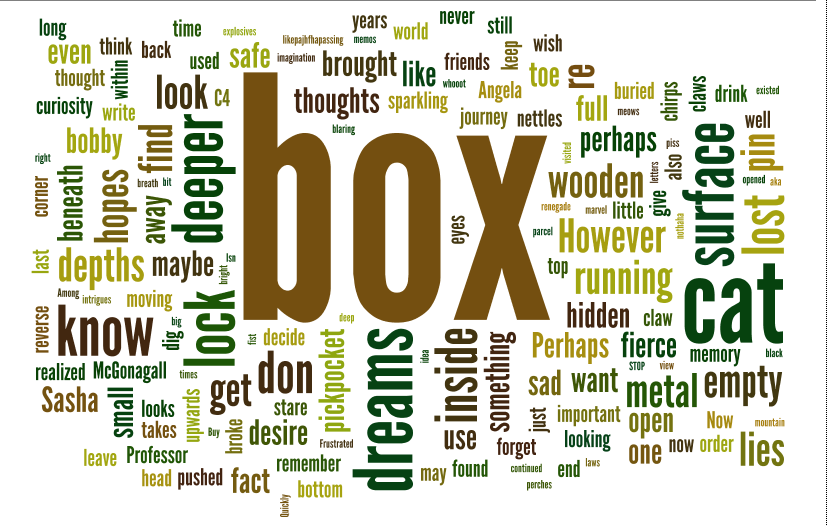

In a group setting, students will work in silence to participate in a back channel conversation while they co-author a textual document with a particular purpose. This purpose may be nebulous or fixed. The backchannel application I use is Today’s Meet and the document will be created in Google docs. Each student will be invited to share the document and simultaneous editing will be possible. Google docs also has a “chat” capability which may or may not be used. I will begin the class by explaining the task and the “rules” as well as work with the students to determine the loose direction of the task. Once we have a sort of trajectory, we will begin and allow the interaction to take us where we will. The backchannel and the doc will be projected on the screen for all to witness (though it occurs to me that maybe just the backchannel might be appropriate). After the time is up, we will take the product (the created text) and render it in a text visualization tool. A teacher could then take this one step further and have the students create a found poem from the word cloud that serves as their reflection on the task.

After I execute this today, I will post the products as an exemplar.

-gunita.

Works Cited:

Kress, G. (2000). A curriculum for the future. Cambridge Journal of Education, 30(1), 133-145.

The Today’s Meet chat transcript was lost to the ether but, interestingly, the group chose to communicate via in-doc Google chat instead.