As I prepare for my summer class, it occurred to me that I could radically re-organize the classroom experience for the students. But at what cost?

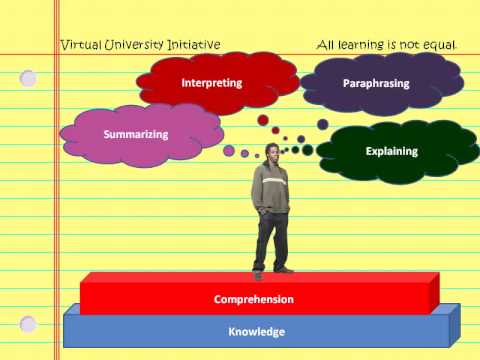

In the last few years I have worked inexorably towards an educational environment that moved steadily away from rote learning, and towards collaborative education. The most vivid example of this evolution is my assessment procedure (formally known as exams). Although assessments have been the scourge of every generation and age of student from time immemorial, they also seem to be a necessary evil.

Like democracy, the theory of the assessment is flawed, but it is currently the only effective means of measuring acquired knowledge. The results of an assessment (e.g., a degree) assure an employer that the potential employee really does have the necessary skills to complete the job. However, even this bald fact of life is under review as more and more employers are conducting their own assessments during their job interviews, having lost faith in the degree process. Be that as it may, I have abandoned that silent rite of passage – the hushed exam room with a ticking clock, pencils at the ready. I began with in-class assessments that could be written inside or outside of the classroom during exam times, then added an open-book policy, until I finally graduated to online exams.

The growing dilemma

With the evolution of my classroom and its procedures in mind, I was recently musing about a new classroom procedure that was radical even for me. Before I explain my latest thinking, I need to explain that my summer lectures are about three hours long, consisting of two weekly winter classes back-to-back. Three hours may seem like a vast amount of time to lecture and even more challenging, to sit through as a student, so I countered the potential for lapses in concentration by using a video and audio excerpts, and even music performances conducted by myself. I overcame the boredom factor, and encountered another problem. Now, with the bells and whistles cutting into actual lecture time, I did not have enough time to say everything I felt needed saying. I sometimes found myself having to finish up a previous lecture in the first few moments of the next lecture.

My content became even more challenged when I introduced an entire half hour of student presentations in each “week”. Suddenly I had even less time to talk, and yet the presentations turned out to be wildly successful. Students were anxious to share their experiences, either in World Music or Popular Music, using my guidelines and the media resources in the classroom. I was astounded at the variety of interests, so there was no turning back to the old days of lecture downloading/uploading.

I have managed to retrieve some of my missing lecture time by mounting the assessments online, instead of in the classroom, but I am still haunted by the specter of the modern needs of the Millennial generation. They are surrounded and engulfed in knowledge available at the fingertips. I think they need experiences to contextualize their place in that vast ocean of information.

Workshops

So with this in mind, I imagined the following scenario in which workshops would occupy the entire time of the second lecture. Here is a preliminary list of those workshops:

Class 1: Introduction and key concepts including ethnography

Workshop: Students pair off to conduct 5 minute ethnographies of each other, then present their findings to the class

Class 2: a personal sample of Word Music interests based on cultural diffusion

Workshop: Student learn dances to additive rhythms

Class 3: introduction to ethnomusicology and hybridity

Workshop: Students pair off to create pop fusions, then present their conclusions to the class

Class 4: Canada’s Intangible Cultural Heritage: the fiddle

Workshop: Students learn to jig, reel and “chair dance” (i.e., podorhythm)

Class 5: an introduction to Canada’s songcatchers

Workshop: Students conduct a sing around / karaoke (on a purely voluntary basis)

Class 6: Powwow cultural background

Workshop: Students listen to a First Nation guest speaker

Class 7: Powwow music and dance

Workshop: Students learn powwow steps

Class 8: Zen Buddhism and meditation

Workshop: Students participate in a Zen meditation exercise and ritual

Class 9: Zen Buddhism and music

Workshop: Students perform choral Zen music-making

Class 10: English country dance

Workshop: Students learn a country dance

Class 11: English morris dance

Workshop: Students learn a morris dance

Second thoughts

Obviously these workshops would be highly entertaining, but would they fulfill the mandate of the university and the educational needs of the students? I’m not certain. One obvious change is the greatly reduced amount of lecture time. Instead of the current 2 hours and 10 minutes (not including presentation) the lecture time would be 1 hour and 15 minutes – almost half. On the other hand, in the world lectures, 1.25 hours of lecture time is very generous, almost taxing the attention span of the modern audience. A puzzle, to be sure.

I can hear critics scoffing at my scenario. “It’s nothing more than edutainment.” “Learning-light, perfect for the student who is looking for a quick and easy 3 credits.” “Students will emerge from the course with a pocketful of stories and scant information about ethnomusicology.” “With classes like the one you are proposing, there’s no wonder that the baccalaureate degree is so severely devalued today.” “How is a student supposed to get gainful employment if they take courses that don’t give them facts and theories to use in their jobs.”

No doubt about it, my proposal would be monstrously out of place in most of East and South Asia. It would not even remotely prepare them for their graduation exams.

Full-time ethnomusicology faculty members can fulfill this urge to contextualize ethnomusicological theory by directing ethnic music ensembles. The ensembles are, for all intents and purposes, year-long workshops. And they have real-time value – 2 credits towards graduation.

In weak defence, I could say that my workshops offer greater variety than the four ensemble offerings currently available, even if my versions are somewhat facile and introductory in nature. They would be perfect for the student interested in ethnomusicology but who doesn’t have the time to participate in a year-long ethnic music ensemble. And they certainly contribute to the 21st century’s concern with experiential and collaborative learning which could be applicable across the work-force.

But there’s no escaping the criticisms mentioned above, which is why I won’t be doing the workshops any time soon.

What do you think? Add a comment, below.

Readings

James A. Davis, editor (2012) The Music History Classroom

Thomas Rudolph and James Frankel (2009) YouTube in Music Education

Steven Feld and Keith H. Basso, editors (1996) Senses of Place

Lucy Green, editor (2011) Learning, Teaching, and Musical Identity: Voices Across Cultures

Ted Solis, editor (2004) Performing Ethnomusicology: Teaching and Representation in World Music Ensembles