A few months ago I posted a UBC blog entitled “Honouring Tanaka Sensei”. I described the revelations and adventures I experienced from my encounters with that very great man.

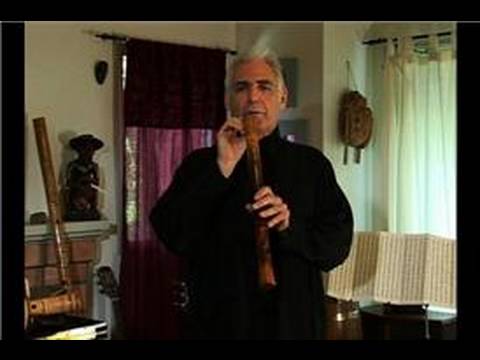

Now it’s time drop the other shoe. At the same time I was studying with Tanaka Motonobu of the Dōmon-kai (土 門 会) Kinko-ryū (琴古流) school of shakuhachi playing , I was also receiving instructions and insights from another great shakuhachi teacher, Kojima Toyoaki (小島豊明), of the Myōan Kyōkai (明暗協会) Taizan-ryū (男山流), a school of playing entirely different from the Kinko-ryū.

The Myōan Kyōkai is an association of shakuhachi players who are based in a Buddhist temple called Myōan-ji (aka Meian-ji 明 暗寺). The members are essentially laymen (and one or two laywomen) who pay obeisance to Buddhism and their quasi-historical founder, Kyochiku Zenji (虛竹禅師). The members perform Zen Buddhist rituals and group “meditations” in the form of solo and unison shakuhachi performances. The temple does not house a rōshi (老師)and his community of (male or female) Buddhist trainees and administrators, but it does have one resident monk who oversees the temple and is sanctioned to conduct ritual activities. The building is found within a temple complex called Tōfuku-ji (東福寺), an inner city comprised entirely of temples and administration buildings with religious and intellectual Zen Buddhism at its core.

Discoveries and revelations

On my first visit to Tōfuku-ji, a group of temples inside a common compound, I found myself wandering through a maze of alleys and byways until I finally found the modest Myōan-ji temple and its beautiful gardens. I was greeted by the resident monk who graciously gave me an interview. He recommended Dr. Kojima as a source of more information and expertise.

I ended the interview by playing one of the sacred shakuhachi solo pieces (honkyoku 本曲) in front of the statue of Kyochiku Zenji. Much to his surprise, I played it on a western (Boehm) flute.

Despite the common belief that the performance practices of the shakuhachi are unique, they are all available to a proficient player of the western flute. Even the timbre shifts are accessible, given the new design of the head joints. I often wonder if I was the only person to have ever played a Western flute in the temple. The usually reserved monk was very intrigued.

Within days of the interview I found myself in the waiting room of Dr. Kojima, a resident MD in the Japan Baptist Hospital. It was the beginning of the lunch hour, just after his last morning patient. He greeted me warmly and led me to a traditional tearoom (ochaya (お茶屋) on the verdant grounds of the hospital. The medical centre takes full advantage of its location on the wooded slopes of Kyoto’s eastern mountain slopes, Higashiyama. After a few brief words of introduction he asked me to play my shakuhachi for him. Then he did the same for me. From that point on, he shared his knowledge almost entirely in the form of music lessons instead of interviews. Unlike my lessons with Tanaka Sensei, Dr. Kojima and I rarely discussed the intellectual and spiritual basis of the shakuhachi. He preferred to teach in the traditional manner, through imitation and repetition of each melodic fragment (kata 型). Although that style of rote instruction is often interpreted as a mechanical process by Westerners, it is balanced by the teacher’s intense concentration on the each musical minutiae and a general spiritual demeanour which conveys the organic spirit (kokoro/shin 心) and “life” of the music.

My weekly lessons were bracketed by a long commute by foot to the hospital along the famous Philosopher’s Walk (哲学の道, Tetsugaku no michi) which borders a peaceful little canal that meanders between ancient temples, groves of cherry trees, and traditional houses. The lessons and the walks were intoxicating. And the music I was being taught was a major revelation, given that I was studying many of the same titles in the other school I was studying. The contrast between the music of each school’s piece with the same name was more than a subtle difference in performance styles. The many performance practices and even the notations were significantly different. Unlike the Kinko-ryū which emphasized melodic craftsmanship achieved with a multitude of complex performance practices, Dr. Kojima’s school valued utter simplicity and bareness. And yet both schools value wabi-sabi ( 侘寂), an aesthetic that valorizes primitive tone which is seemingly improvised on the spur of the moment.

Two conundrums

As I settled into a weekly routine of shakuhachi lessons with Dr. Kojima (and Tanaka-san), two vexing problems arose.

Because I was a professional flutist, I was learning how to play the repertoire at a furious pace compared to traditional beginners who normally learning how to play the instrument as well as play the literature. The marvel is that the repertoire perfectly suites their needs with its minimal melodies and ultra-slow pace. But rather than being an advantage, my advanced technique was viewed as a hindrance. I was missing the point. The long and rocky path to proficiency mirrors the struggle to achieve Zen Buddhist enlightenment. The slow and painful progress can even echo the near impossible demands of a kōan (公案). “How can I musically meditate when I can barely make a sound?” My dubious advantage was complicated further by my extensive studies in Buddhology which allowed me to see behind the instruction to its Zen Buddhist context. But rather than illuminate Zen truths from hard-won experience, I was glibly identifying each moment of discovery with terms and concepts I had learned in my university studies. I was not following Bodhidarma’s classic (and contested) explanation of the Zen experience:

A special transmission outside the scriptures; (Kyōge betsuden 教外別傳)

No dependence upon words and letters; (Furyū monji 不立文字)

Direct pointing to the human mind; (Jikishi jinshin 直指人心)

Seeing into one’s own nature and attaining Buddhahood. (Kenshō jōbutsu 見性成佛)

Even though my flute-playing skills were an obvious if problematic advantage, I never allowed them to obscure or detract from my deference and respect. We worked through each honkyoku note-by-note, with never a word of complaint from me. Later, I wrote down my experiences of each lesson at home, with academic commentaries and personal musings, in the same manner as my follow-up with my lessons with Tanaka Sensei. I compiled quite a tutorial for my personal use and my graduating thesis.

In addition to the flaw of proficiency I just described, I was confronted with another dilemma. By studying with sensei in two different schools, I was crossing a dangerous line where students never study outside their school for fear of having their allegiances questioned. I had already established my commitment to the Kinko-ryū. Although I had only intended to conduct interviews with Dr. Kojima, my interviews were transformed into a shakuhachi lesson designed for a beginner in his school. As I returned again and again for information, I was instead offered “lessons”. It slowly dawned on me that I was becoming a shakuhachi student associated with another school. This quandary is somewhat paralleled in the west where a music student might take music lessons on the same music instrument from two teachers simultaneously, also viewed askance if not out-and-out transgression. On the other hand, taking music lessons from one teacher, then another in sequence is commonplace, and even recommended. I look back at my own string of flute teachers with great pleasure. Unfortunately, for the purposes of my research, I had to telescope this well-known path of sequential instruction into a simultaneous learning experience.

The Inner Circle

Dr. Kojima was very kind to me. He drew me into his inner circle of students which included one other westerner, a man my age named David who was born and raised in Kyoto. His father was the director of the Baptist hospital where Dr. Kojima practised. Unlike me, his interest in the shakuhachi was confined to his own personal curiosity whereas I was steeped in a research project that occupied almost my every waking moment.

Both David and I were given extraordinary glimpses into a closed world – the inner workings of the Myōan Kyōkai association. One of the most surprising occasions was the invitation to participate in the Mifune “three boat” festival (Mifune Matsuri 三船祭). The festival features over a dozen traditional boats filled with three kinds of traditional performance artists, floating leisurely on the large Osagawa pond on the eastern side of Kyoto’s Arashiyama hills. During the time of the glittering courts, the purpose of the entertainment was to entertain the leisurely courtiers with art music and dance in a novel manner. (I was reminded of Handel’s Water Music.) We performers reproduced the occasion for the local populace and the few lucky tourists that got wind of the event.

More important occasions were the group lessons called Suizen-kai (吹禅 会) also known as Kyochiku Zenji Hôsan Kai (虛竹禅師i 奉賛 会), and the yearly recitals (Shakuhachi Honkyoku Senkoku Kenso Taikai (尺八本曲全国献奏大会).

The recitals were filled to capacity with some 50 plus players crowded into the main hall of the modest temple. They were exhausting. The association seemed to have a come-one-come-all policy to shakuhachi players of all traditional schools and associations which taught honkyoku according to the dictates of their school’s style. The open invitation meant that anybody could play, good or indifferent, resulting in eight or more hours of three-minute solo and unison performances, performed at the slowest pace possible, as required by the tradition in all the schools. At one of the recitals I attended, as a member of Dr. Kojima’s coterie, I had an opportunity hear Riley Lee (now a famous Australian shakuhachi player). He made a very impressive entrance, surrounded by devoted fans. At the same recital Andreas Gutzwiller (another now famous European teacher/player) was hovering around the edges, taping all the performances. At least, I think it was them. Unfortunately both men left the recital before I could introduce myself. There was also an amazing and extremely rare performance of a honkyoku by a woman who played a honkyoku on a traditional transverse flute, a shinobue (篠笛).

The purpose of the group lessons was to maintain a consensus of the performance practices of a particular school of playing that exists within the Myōan Kyōkai assocation – the Taizan-ryū (男山流). The lessons were (and are) conducted by the head teacher (rijichō 理事長). The Taizan-ryū originated with Higuchi Taizan (樋口 対山, 1856-1914) who was also one of the founding fathers of the Myōan Kyōkai. The association was created in 1883 (Meiji 16) for the express purpose of preserving the repertoire of the defunct Fuke-shū (普化宗) and its community of komusō (虚無僧), the Zen Buddhist flute-playing monks of long ago. The Fuke-shū had been banned in 1871 along with many other Buddhist institutions that were purged (haibutsu kishaku 廃仏毀釈) during the Meiji era and the rush to off-load redundant institutions that were dragging the pace of westernisation.

Even though the ban was eventually lifted in 1881, the Zen Buddhist sect was never re-constituted, presumably due to a lack of interest among young men who were more interested in becoming Zen Buddhist acolytes in the mainstream Zen sects. However, a large body of laymen players had been slowly arising, even during the earlier Tokugawa era, ready to replace the komusō with their own style of lay devotion. They were naturally following in the footsteps of the ancient precepts of Vimalakirti (Yuima 維摩) and other great “householder Buddhists” (aka Sk, upasaka, Jp ubasoku 優婆塞 ). Higuchi Sensei was one of the most prominent of these revivalists. For his efforts, he received the designation of 35th abbot and the official title of KŌDŌ in the newly formed Myōan Kōkai.

As luck would have it, Dr. Kojima is one of the most proficient teachers and scholars of the repertoire of the Taizan-ryū.

Dr. Kojima

Born in 1928 in Himeji City, Hyogo Prefecture, Dr. Kojima began his shakuhachi training in 1951 with Tanikita Muchiku (谷北 無竹, 1878-1957) ROAN, 37th abbot of the Myōan Kyōkai and a prominent student of Higuchi Taizan. Dr. Kojima eventually received his certification (Myōan Dōshu 明暗道主) and the honorary natori (名取) of ISSUI (一吹), in 1969 under the tutelage of the 38th abbot, Koizumi Shizan (小泉止山) RYOAN (ca. 1953-72). Since then, he has taught continuously, including many Westerners such as myself. He has been an active participant in the activities of the Myōan Kyōkai and can be heard every year at their recitals. He has also consulted for several television productions such The Komusō Temple (Komusō no Tera, 1973), The Spirit of the Shakuhachi (Fuke Myōan Shakuhachi no kokoro, 1978) and Zen and Shakuhachi (Zen to Shakuhachi, 1982). His dedication to the shakuchachi and its ideals is also evident in his magazine article “Zen and Shakuhachi”, published by Hanazono (1979, volume 29, pp. 12-18).

In 1991 (Heisei 3) Dr. Kojima was elected to the pre-eminent position of 41st abbot of the Myōan Kyōkai, and given a second official name, HOAN (保安). His lineage extends deep into history, past the rejuvenation of the honkyoku repertoire and the formation of the Myōan Kyōkai to the traditional (and according to some, mythological) beginning of the komusō tradition in Japan by Kakushin (心地覺心, 1207–1298), now designated as the first Kansu. HIs student Kyochiku Zenshi (虛竹禅師) was designated as the second kansu and is depicted as a statue in the alcove of the main hall in Myōan-ji. The tradition of playing the shakuhachi in a Zen Buddhist manner is traced even further back to ancient China and one of Zen Buddhism’s most interesting pioneers, Zhenzhou Puhua ( 鎮州普化, aka Fuke-zenji 普化禅師 ca. 770-840 or 860). His disciple, Chang Po/Chō Haku (張伯) imitated Puhua’s ubiquitous and controversial handbell (rei 鈴) by blowing a single tone on a shakuhachi.

During the 2012 World Shakuhachi Festival in Kyoto, Dr. Kojima opened the program of the Myōan Kyōkai concert by playing Kokū (虚空), perhaps the most revered composition of the sacred literature. It was a very great honour and a fitting tribute to his august position as the 41st Kansu.

As is true of all lay members of the Kyōkai, Dr. Kojima had a “day job” that sustained his interest and dedication before retiring. He was a doctor of medicine with a long and distinguished career at the Japan Baptist Hospital in Kyoto, specializing in geriatric medicine. Not content with simply maintaining his medical practice, he actively pursued research programs which culminated in a presentation on gastric cancer delivered to the 6th International Cancer Congress in Florence, Italy in 1947. He is married with four daughters and several grandchildren.

For a young person such as myself in the long ago, bristling with anticipation and awe as I sat poised on the cusp of adulthood, mentors like Dr. Kojima and Tanaka-sensei are a godsend. They introduce a heightened awareness of life at just the right moment and with just the right spirit of guidance and patience. We should all be so blessed.

Bibliography

James Sanford (1977) “Shakuhachi Zen. The Fukeshu and Komuso,” in Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 32, No. 4 (Winter, 1977), pp. 411-440

Kamisango Yūkō (1974) “shakuhachi no rekishi,” translated and edited by Christopher Yōmei Blasdel as “The Shakuhachi – Its History and Development,” in The Shakuhachi, A Manual for Learning (Ongaku no Tomo Sha, 1988; second edition, Printed Matter Press, 2008)

Norman Stanfield (2013) “Two Perceptions of Music Compared: The Meian and Kinko Schools of Sacred Solo Shakuhachi Music,” in The Annals of the International Shakuhachi Society, Volume 1