MORRIS DANCE AND CULTURAL STUDIES

In 2014 I published a series of posts on my professional Facebook page, Dr. Norman Stanfield, about morris dance (the subject of my PhD dissertation) in the light of various theories of culture. The nature of the posts were brief and casual even though they featured ideas borrowed from communication theories and performativity studies. My readership was comprised of casual readers, most of whom are avid morris dancers but not necessarily cultural theorists.

The problem with Facebook, as many people know, is that earlier posts get shoved deeper and deeper into the bottom of the page as new posts are created, eventually disappearing into an archive. As I thought about this problem, it occurred to me that I could compile all those posts in my UBC blog where they would be accessible and available all at once and in their entirety. The transfer of the posts to the blog also gave me an opportunity to edit them for the sake of flow and clarity.

Morris dance is a common traditional English seasonal custom where a small group of six to eight people dance vigorously in formation, accompanied by live music in an outdoor location. Pre-modern morris dancers, mostly men, were working poor who performed the dance as a means to solicit money (i.e., “pay for play” busking) during seasonal high days and festivals; modern teams are male and female, middle class hobbyists who dance year round, enjoying its “dancercise”, its team camaraderie, and the ambiance of its outdoor performance venues. The dance genre has appeared all over the world where English culture is popular.

Modern and pre-modern teams present six to eight five-minute dances in outdoor, casual settings, in front of happenstance viewers, such as shoppers at a Saturday outdoor market, in a seemingly spontaneous manner (although, in fact, all performances are planned by the teams and sometimes their sponsors in advance). These public performances follow many months of weekly, private practices that are as much social get-togethers as opportunities to learn new dances and perfect existing repertoire. Modern teams will often have an announcer who is similar to an emcee, identifying the team and naming each of the dances just before they are performed. In pre-modern times, a carnivalesque “fool”, aka Lord of Misrule, interacted with the audience..

Morris dance and the month of May seem to go hand-in-hand in the mind of the general public. Given that the most common genre of morris dance is from the Cotswold Hills west of Oxford, where it is usually performed in Spring during May festivals, the association is understandable. However, there are other genres of morris dance that are unique to other English seasons. Nevertheless it is the association of the Cotswod genre with Spring and, coincidentally, its promise of renewal and fertility, that lies at the heart of the general perception, and confusion about morris dance.

The Dilemma

In pre-modern England, morris dance as a “medium of communication” (a la Marshall McLuhan) was familiar to everybody because it was a living tradition and its “message” was simple and crystal clear – pay for play (i.e., busking). Modern morris dance is obfuscated. It is unfamiliar to contemporary audiences and its “message” is frequently garbled. As a traditional custom, it exists uncomfortably in the present.

Today, more often than not, performances of morris dance are difficult to decode by the casual audience member beyond their first impressions – exuberance and in some (many) cases, embarrassment for the dancers. After a performance, audience members will sometimes ask individual members of the team or the announcer questions such as, “What is the meaning of your dance?” or “Are you representing an ethnic group?” In England, the general opinion of morris dancers is scathing, as seen in frequent harsh and satirical descriptions in the press. When questions about meaning and origins are asked by the public, and invective is commonly expressed by the press, obviously little communication has occurred, aside from a colourful, noisy and ignominious display.

The Communication

All dance genres communicate meaning by representing ideas and emotions with a vocabulary of symbols.

Modern and pre-modern morris dance has a basic mandate – to entertain. This basic fact separates it from the many folk dances in England and around the world which are essentially social dances. Neither do they share the same imperative as ritual dances which are motivated by spiritual concerns. Although all three of these dance domains communicate in one way or another, morris dance, like all dance entertainments, has a single goal — to please an audience by optimizing the communication for audience approval and reward.

The theories of communication examine the simple act of speaking and listening, revealing that they can be surprisingly complex as anybody who has tried to make their thoughts known or their perception perfected.

Out of this quagmire of comprehension have come several theories that account for the complexity of communication and possible solutions to thoughts transformed beyond recognition because of historical or contextual change.

Theories of communication include reception theories created by academics like Stuart Hall, once a faculty member in the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies at the University of Birmingham (1964-2002). His ideas are exciting to all performers who want to know what their audiences are actually thinking and feeling.

Reception theories are extended into performativity studies where the means of communication are translated into theatrical conventions and sociology-based dramaturgy.

Communication and messaging is streamed through texts (e.g., language) and paratexts/paralanguage (e.g., body language, costume, accoutrements, etc.). In the domain of modern morris dance (but not pre-modern Morris dance), texts often consist of announcements by team announcers during a performance, hand-outs, media bumph, web sites, and word-of-mouth. The paratexts of pre-modern and modern morris dance are comprised mainly of costume and body language during each dance and the entire time of a public performance (30-60 minutes).

The audiences observing morris dance should not need to know any of these discourses or even the history and competing interpretations of morris dance to enjoy the experience of the dance at the moment of its performance, although they would certainly benefit from the knowledge. It is the performers and their organizers who require its insights in order to make their public presentations meaningful as well as entertaining. To quote Marshall McLuhan (1967), “It’s misleading to suppose there’s any basic difference between education and entertainment. This distinction merely relieves people of the responsibility of looking into the matter.”

The Context

As mentioned earlier, morris teams come from a history of busking. And, like busking around the world, the response of the audiences is immediate and visceral. If the presentation wavers in any respect, the audiences vote with their feet, abandoning the performance site in pursuit of their original agenda (e.g., to shop). If the buskers are good, the public becomes engaged; at the end of the performance, they willingly place monetary rewards into a hat as a form of immediate and spontaneous gratitude. Because no entrance fees are purchased beforehand by the viewers, their responses are free of any biases that come from a financial investment in the event (i.e., purchasing an entrance ticket) or any expectations generated by the advertising that preceded it.

Two kinds of buskers exist, both founded on the principle of immediate, un-mediated reward for their services. There are the musicians who seemingly play for nobody in particular, witnessed by an audience that strolls past them and who may or may not pause to listen, however briefly. An instrument case or hat sits at their feet, silently requesting money for entertainment.

Then there are the interactive street entertainers (e.g., jugglers) who demand voluntary public attention. They have a 30-60 minute, self-narrated show that crescendos to a finale, followed by a joking yet serious plea for monetary reward. The audience numbers increase as more and more passersbys gather to see what’s going on; everybody gets hooked by the performer’s technical skills and humorous bragadaccio.

I believe that morris teams can, and should, be a mix of both types. The dancers and musicians, as usual, perform a medley of dances like the music busker, mutely exhibiting their art. And, like the jugglers described above, a team announcer and any other intermediaries interact with the audiences between each dance set.

Like the musician buskers, described above, most, if not all, morris teams perform their dances as perfectly as possible, given their weekly practices all winter. It is the performance as a whole that needs attention.

It has been my experience that teams devote little to no attention to this non-dance aspect of their public presentations. And given the precarious nature of busking, described above, the pressure is even greater to craft a viable public performance.

The Morris Dance Message

Unlike pre-modern morris, the meanings of the explanations, symbols and actions of the modern dancers are surrounded by controversy, even among the dancers. The result is that, in my experience, the messages and their communication channels are frequently in disarray and conflicted, in addition to being foreign to modern (western and especially global) culture. One or two key members of the team will take it upon themselves to explain the symbolism of morris dance to the public on their team’s handouts and in their roles as team announcers.

Two of the most common “texts” are the Arcadian and Fertility tropes which are highly contentious. The latter resembles a Cargo Cult, given its complete lack of supporting evidence and endorsement by the academics who study morris dance.

Early commentators, including Shakespeare, described morris dance as a custom performed by “peasants”. When later observers called antiquarians, took a closer look at morris dance, they believed that it represented the simple pleasures of a Springtime recreation conducted by the country folk, untainted by the blight and anxieties suffered by jaded and world-weary city dwellers. The trope was called Merrie England, championed by outliers such as William Morris (1834-96) and the Arts and Crafts movement, later ripped apart by Kingsley Amis in the novel Lucky Jim (1954).

Merrie England’s interpretation of morris dance was anthropologized circa 1900 when it was decided that, underneath its benign bucolic frolic, there was a vestige of a prehistoric Springtime fertility cult. The speculation seemed to echo the many ancient fertility narratives compiled by Sir George Frazer (The Golden Bough) such as the legend of Persephone/Prosserpina. Many modern-day morris teams and neo-pagans adhere to the fertility interpretation. Some of them even claim, either in jest or in earnest, that morris dance can actually cause agricultural and human fertility because of its power of ritual efficacy. This imagined power is shared by neo-pagans and even the establishment when they enact the planting and decorating of a maypole.

Many modern morris teams are sympathetic, suspicious or equivocal about morris dance as a vestige of a fertility ritual. Some announcers “send up” the fertility of Morris dance by “giving the public what they want to hear” – sensational claims about the fertility that comes from “witnessing” morris dance. For example,a team’s announcer mockingly or seriously alerts the audience to the luck or danger of becoming pregnant if one gets kissed by a morris dancer, or even touched by him.

The Arcadian and Ferility explanations have been debunked. Unfortunately, the public and media unknowingly accept these bogus announcements as gospel and spread them around as solemn (or laughable) claims.

I suggested another interpretation of morris performance based on misrule, as defined by Mikhail Bakhtin. The morris dancers of old followed the template Bakhtin had theorized in a related context — carnival: once a year, those below rule those above, performing satirical street theatre for recompense by their audiences. The butt of their satire were the elite, ruling classes, and their theatre aimed to generate Carnival Laughter, using parody to laugh AT, not with, the ruling classes. Even then, the entire occasion was so dominated by ribald, roaring humour and a topsy-turvy inversion of the usual order of social status, that even the ruling classes found themselves laughing, willingly donating money to the carnival. Those who did not could be subject to a kind of extortion in the form of services witheld or denied during the rest of the year, or the kind of vandalism seen on Mischief Night.

So how does misrule function in Morris dance? Below is one model that could be observed in one commonly seen genre, Cotswold morris dance.

It occurred once a year (Whitsuntide in Spring), those below (the working poor) ruled those above (the village elite) performing theatre of parody (sending up Country Dance a la Jane Austen) door to door, outside the homes of the wealthy or in the fair grounds of seasonal celebrations, expecting pay for play (facilitated by the Collector). These four conditions can be applied to all the other styles of morris dance. For example, Molly Dance: once a year (Plough Sunday following the 12th day of Christmas), those below ruling those above (the ploughboys and other farmhands) performing theatre of parody (sending up Feast Dances), expecting pay for play (facilitated by a collector) as they moved door-to-door. This pattern operates for mummers troupes as well.

The great advantage of this form of text is that it closely matches the history and lifestyle of the working poor in pre-modern England outlined by E.P. Thompson and other cultural historians.

The Morris Dance Communication

Having established a credible message, the next step is to generate an unproblematic communication.

Modern morris teams communicate the chosen meaning of their dance to their audiences by distributing pamphlets during their performances describing the history and function of Morris dance and their team in particular. They may also have a designated announcer who provides learned or ribald mini lectures between each dance. I think that all of these media ultimately fail due to the transient nature and attention span of the audience.

I prefer a street theatre format similar to agitprop to provide the avenue of communication. And, following Marshall McLuhan’s dictum that the medium is the message, the actions and words of the morris dancers should embody the message using a blend of paratext and spoken text, completely obviating the usual pamphlets and/or public announcements.

A traditional morris theatre “cast” consists of a team of 6-8 dancers with a few extra dancers standing at the side, one melody player, sometimes assisted by 1 or 2 percussionists, a Fool (aka morris clown) and a Collector. They are the key markers of misrule, the former embodies the Lord of Misrule, the latter, pay for play. As they go about their traditional business, addressing the audience and the dancers, they can surreptitiously convey the spirit of misrule.

Most modern teams alarmingly dispense with the Fool and Collector (although it is to their credit that they maintain the tradition of live music accompaniment unlike many other ethnic dance ensembles). The exclusion of the two characters occurred early on when the revivalists led by Cecil Sharp focused almost exclusively on the dance as physical recreation and rational education.

Whereas the dancers are mute, the two characters have speaking roles that are reminiscent of the actors in a mummers play. The Fool is the principal interlocutor between the dancers and the audience. He (or she) delivers quasi-improvised pronouncements, gibes and reactions to comments from individual and collective audience members. S/he also speaks to dancers about their dance prowess, or supposed lack there of. The Fool’s language must be in present tense; instead of the usual announcer’s banter; instead of “back then they…”, s/he says “now we are…”

The Collector solicits and accepts random offerings of money with words and actions in appreciation for the street entertainment provided by the busking morris dance team.

The role of the Collector can be a tricky affair, given the restrictions placed on soliciting money in certain venues such as festivals and private/corporate public spaces. If this problem occurs during a morris dance presentation, the Collector can feign collecting and maybe even stage a token offering.

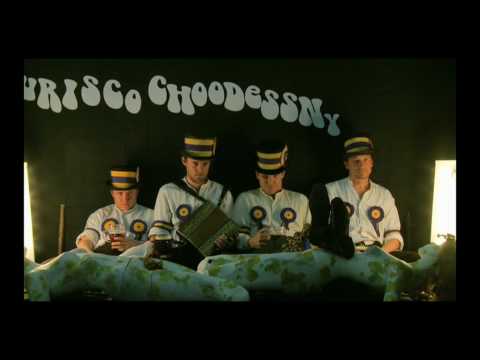

Even within Morris teams that have a Fool, the Collector is often overlooked. Look for the Collector in the following video at the 5:08 to 5:10. He makes such a brief appearance that he must not be of any real interest to the videographer.

Both the Collector and Fool (and musician/s) can exchange quips similar to Tommy and Betty in rapper dance (or even Punch and Judy). A morris team director (i.e., squire) could write a rough script consisting of verbal jousts and exchanges in the style of a mummers play. The excerpts could be performed between dances, as the team reorganized for the next dance event. The script could be open to improvisation, although it should be able to stand on its own. It is possible to create an overarching dramatic event (i.e., introduction, complication, climactic resolution) involving all the members of the “cast” — the only limitation is one’s imagination.

Most importantly, their humorous exchanges can go a long ways towards voicing the meaning of morris dance by embodying misrule behaviour found in pre-modern Morris dance. Instead of rehearsing and performing medlies of dances in the standard 30-60 minute public presentation, an ideal team would actually construct a single, theatrical 30-60 minute “show” with dancing and speaking. In short, Morris Theatre (or Morris Dance Recital, or Morris Dance Musical Theatre).

The Critics

My concept of “morris theatre” has been criticized for being a historical re-enactment like LARP (Live Action Role Playing), Cosplay, the SCA (Society for Creative Anachronism), and professional and volunteer re-enactors who populate historical military ventures and musum exhibits with people in period costume, doing period things.

One critic even went so far as to describe it as an example of museumification. Another critic said, “we are not representing morris dancers; we ARE morris dancers”.

If my “theatre of morris dance” requires all academic theory and explanation described above to buttress the dance custom, is it valid? Can my morris theatre ever be made simple and self-evident for those who avoid academic intervention like the plague? I say “yes”. But, even though I would personally enjoy creating the morris dance performance scenario I am advocating, getting others to feel and do the same in the past has been a tremendous, even overwhelming, challenge.

Some morris dance teams, confronted by the plethora of conflicting And controversial interpretations, and alternate scenarios like my theatre of morris, choose to “shut up and dance”. Others completely abandon any pretext of being traditional, choosing to cheerfully maintain the garbled status quo in an anarchic, pseudo-carnival atmosphere completely out of carnivalesque context.

Maybe the prison warden in the movie Cool Hand Luke was right.