Chinese New Year occurs on January 23 this year. The fact that we even have to announce the date reveals that it changes each year. That’s because the date for Chinese or Lunar New Year depends on how the annual cycle of the Earth orbiting the Sun interlocks with the roughly monthly cycle of the Moon orbiting the Earth. The event that lights the fuse on the celebrations is the December solstice.

There are some parts of the Northern hemisphere where it doesn’t get very cold in the winter, like Vancouver where I live. But talk to anyone living just about anywhere else, and they’ll tell you through chattering teeth, that December 21 is the middle of freakin’ winter, not its beginning, as our Western calendars proclaim.

On Western calendars, winter begins in the Northern hemisphere on the December 21 solstice, not when it starts to get cold out.

In other words, those freezing cold days on the Prairies in November? Fall, not winter. Changing the name doesn’t make them any warmer.

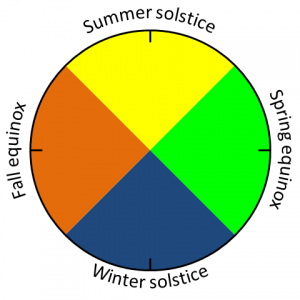

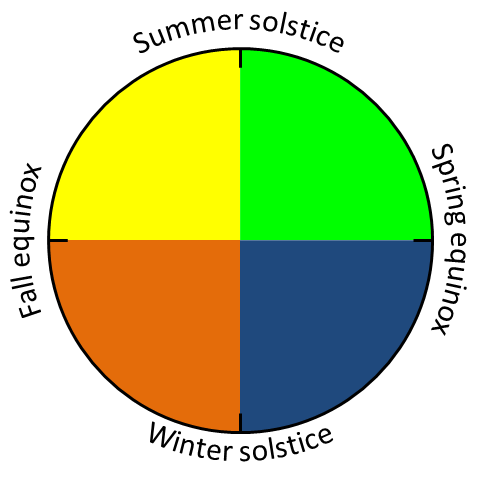

The ancient Chinese astronomers and calendar-makers knew their hot from cold, though, and recognized the December solstice is the middle winter, just like March is the middle of spring, June is the middle of summer and September is the middle of fall:

Chinese New Year marks the end of winter and the beginning of spring, the transition from dreary blue to vibrant green in the diagram above. Now the Lunar Cycle comes into play. Each season — winter, spring, summer and fall — is roughly 3 months long so there’s about a month and a half from the solstice to the New Year.

Or a lunar cycle and a half.

Here’s how it works: take note of the Moon’s phase on December 21 and let the lunar cycle play out. Last year, for example, there was a new Moon on December 24, 2011, a few days after the solstice. So began the last lunar cycle of the year which finishes on Monday, January 23, 2012, Chinese New Year.

Depending on the Moon’s phase at solstice, the date for Chinese New Year can vary by about a month. This year, we’re pretty close to the earliest possible date. For next year, though, there are new Moon’s on December 11, 2012, on January 11, 2013 (the end of the middle, winter solstice cycle) so that Chinese New Year won’t be until February 10, 2013.

If all this dependence on the phases of the Moon seems a little archaic and superstitious, let me ask you a question: When are Canada Day and Independence Day?

No brainers: July 1 and July 4.

What about Halloween? October 31. D’uh!

Okay, smarty-pants, when’s Easter this year?

Er, um, just a sec while I… [google google google] … Sunday, April 8, 2012.

You see, the phase of the Moon also plays a part in determining the date for Easter, which is defined as the first Sunday after the first full Moon after spring equinox. This year, the Moon is pretty close to new at the equinox and there won’t be a full Moon until Friday, April 6. Easter occurs that Sunday, April 8. The fact that the most important date in the Christian calendar depends on the phase of the Moon, and that preparing for Easter depends on predicting those phases far in advance, are reasons why the Vatican has had an observatory for more than 250 years.

There is long and prestigious history and tradition of Chinese astronomy and time-keeping. I’ve only scratched the surface here, and my sincerest apologies if I’ve misrepresented that tradition through my over-simplification or just plain got-it-wrong-edness. In any case, be sure to take a moment next Monday to wish your friends a hearty Gung Hei Fat Choi!