The Skeena River Room, room 317 in the Irving K Barber Learning Centre, is a group study room that is named after the Skeena River, the second-longest river entirely within British Columbia’s borders (the largest being the Fraser River). Six-hundred and twenty-one kilometers long, it flows south and west through the Skeena and Coast Mountains, reaching the Pacific Ocean at Prince Rupert.

Port Essington, Skeena River, 1888, BC124

For thousands of years, the Tsimshian (“People of the Skeena”) have lived along the river; the Coastal Tsimshian live near the lower part of the river and the Gitksan live on the upper part of the Skeena River. George Vancouver visited the mouth of the Skeena River in July, 1793, but it wasn’t until the 1860s and 1870s that persons associated with the Gold Rush and railway began to travel to and settle along the river. In 1876, salmon canneries were built along the Skeena River. Operating along the river from the late 1870s to the mid-1980s, at one time there were as many as 18 canneries along the Skeena.

In Rare Books and Special Collections, we have various records and plans of salmon canneries that operated in British Columbia, and in particular along the Skeena River. For example, in the Inverness Cannery fonds, there are plans, financial records and correspondence relating to this cannery constructed along the Skeena River in 1873. The J.H Todd and Sons fonds also contains records concerning the Inverness Cannery.

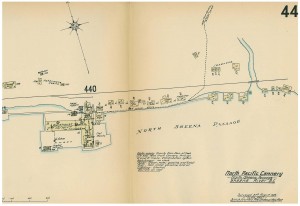

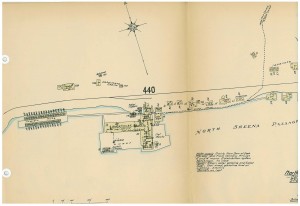

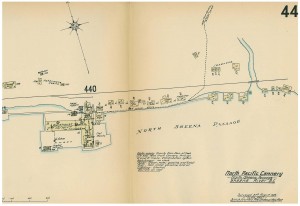

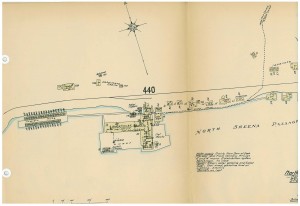

It is also very interesting to consult the 1924 fire insurance plans of Skeena River salmon canneries in the collection of Plans of salmon canneries in British Columbia together with inspection reports on each, that are part of the records of the British Columbia Fire Underwriters’ Association. This collection includes the plans of 12 canneries that operated along the Skeena in the early 1920s: Inverness Cannery, North Pacific Cannery, Dominion Cannery, Sunnyside Cannery, Cassiar Cannery, Haysport Cannery, Alexandra Cannery, Balmoral Cannery, Port Essington Cannery, Carlisle Cannery, Claxton Cannery, and the Oceanic Cannery.

Fire insurance plans are detailed large-scale maps of cities, smaller municipalities, and industrial sites that were produced from the late 1800s to the mid-1960s. The object of these maps was to show the character of any insured building. These plans were compiled by the fire insurance underwriters to assist their agents in assessing and controlling the risks of fire. Various symbols and colours were used to indicate the following characteristics: the shape and size of a building; the type of construction used; the existence of fire protection facilities; and the use of the building (e.g., a restaurant, a laundry, etc.).

The fire insurance plan of the North Pacific Cannery is revealing for a number of reasons. In addition to documenting the number and types of buildings of this cannery originally established in 1889, the plan shows, for example, that in 1924, the Japanese, First Nations and Chinese cannery workers were housed in separate buildings:

Sheet 44, North Pacific Cannery, RBSC-ARC-1272:F9-8

Sheet 44 (part 2), North Pacific Cannery, RBSC-ARC-1272:F9-8