Hey! Here is the direct link to our mapping project:

Reflection on Reflection (I copied Marianne’s title, haha)

I think taking this course has encouraged me to question every part of my life I’ve previously thought of as a norm. By using sociological imagination, I realized how ignorant and unchallenging I was to the social system. I could describe myself as a sponge, just absorbing all the social forces to empower or disempower my identity. I really liked how diverse our topics were and how engaged our class was to each topic. The class felt very casual but I believe our discussions provided a site of excavating treasured insights. To be honest, I hated doing the blog assignments, reading responses and presentations as it was very challenging and tedious for me. However, I think this really forced me to think like a sociologist and I really learned from the experience. Just from the facilitation of the class, I could see bits of theories from the readings put into practice, unconsciously, in our actions. I guess this is why I like sociology, since what we’re learning is what we’re living.

Anyways, I would like to thank all of our facilitators and classmates. Everyone was respectful and definitely had a lot of character in them. It was just one course but I feel like I got to know everyone on a more personal level, just by talking about our identities. I still don’t know if I have an absolute answer to the question I asked on the first day of class, “What is my true identity?” But I could say that my identity was formed, and still in the progress, by how I intake or resist society.

A Reflection on Reflection 對反思的反思

My identities are complex. They keep changing and shifting focuses depending on context. And They should always be intersectional.

“my feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit.” – Flavia Dzodan

Reading this quote on Facebook today made me think of my positionality in relation to the #Ferguson issue. The jury officially announce that the white male police, Darren Wilson, face no charge shooting 18-year-old black citizen Michael Brown to death on August 9th in Ferguson, Missouri, United States. Started from Ferguson, a city with a large black community, solidarity events and protests spread over the U.S. and some parts of the world, many tagged as #BlackLivesMatter. Learning from Alice Goffman’s lecture earlier this semester that in low-income black communities, young men have to face policing, arresting, and killing in their everyday life in the U.S., I do not just see the shooting and the jury decision as a single issue but a systematic problem that put the African-American ethnic groups in fundamental disadvantage and injustice.

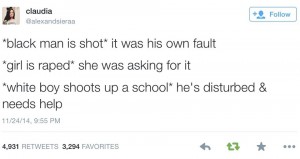

Why does this disturb me and why it is relevant to me? Because in this context I quickly see myself as a person of colour in a white-settler society (Razak, 2002) that is established upon white privilege. At the same time, along the line of Razak’s intesectional approach to space, gender, and race, I am aware that my position as an ally with the #BlackLivesMatter protest is not simply related to my skin colour, but a self that intersects with multi-dimensional identities such as in ethnicity, gender, and social location. To expand my thoughts I think it is good to start with this tweet:

[first, let me try to type in my thoughts in Chinese]

這幾行字簡約卻充滿爆炸性,因為其啓發我將種族和性別不公聯繫在一起。這在我看來,也是交織性女權主義的魅力。

[Then, I translate them into English]

These few lines are simple but explosive, since they push me to further see ethnic and gender oppression together (in a white-dominated patriarchal system). To me, this is the charm of intersectional feminism.

[as I learn sociology through an English-speaking education, I soon run out of words in Chinese and return my reflection to the English thinking mode]

To be sure, paralleling the experience of the “black man” and “girl” in contrast to the experience of the “white boy” does not mean that we should draw an equation mark between the two. My experience being a Chinese woman is very different from that of a black man. But the experiences of the blamed and the redeemed connect me to the movement of black people’s rights.

When I was taking SOCI 101 sociological theories in another university, I was confused about the feminist theory because I saw it as a combination of all kinds of social justice arguments. To be honest, I was not impressed at all and I came to resist the “feminism” label. I had negative feeling towards feminism as feminists make claims over almost every issue on injustice. To simply put, I was tired of seeing the label “feminism” everywhere. At the same time, “feminism” was a term that I often associated with the images of radical men-haters and naked FEMEN.

But now, when I am reflecting on how I have been reflecting on feminism during these few months, I see the value of feminism that intersects every social components together. Which means, nothing should be explained merely by race, gender, or class, etc. — it should be explained with these all together.

I first heard of the term “intersectionality” from the courses offered by the UBC Gender, Race, Sexuality, Justice program. I got to talk about it further through learning about it in some public lectures, and interacting with my friends who self-identified as feminists (mostly male!). This semester is very special to me in terms of the process of feminist self-realization. I never publicly claimed to be a feminist until I take SOCI433, which provides me with an intersectional approach to see my identities and other’s identities. The classroom goes beyond the physical space into the virtual space (Facebook group) of public discourses, and allows me discuss feminist topics and issues such as Emma Watson’s UN speech and rape cultural on UBC campus with friends and classmates. More importantly, throughout reading feminist writings by Azaia, bell hooks, and Beckie, I realize that feminism is a way of thinking of the world intersectionally, and acknowledging our own limited but international perspectives. For example, early in Azaia’s thesis, she acknowledges that her writing comes from a perspective of a white urban working-class female (2014, p. 20). In bell hooks writing, she also make it clear of her positionality as a black female.

After all, in this post I touched lots of bits and pieces of my identities. You may think there is no “theme” or a major theory. But this is exactly my point. In this post I try to briefly show you how my identities are intersected:

- my gender intersects with my ethnicity, which make me an ally of the #BlackLivesMatter;

- Chinese as my first language (everyday, reflective) intersect with English as my second language (academic, critical, reasoning)

- my past perception of feminism intersects with my current experiences of feminism.

- my social position as a UBC sociology student intersects with my gender, class, race, and other identities, which provide me with resource and access to critical-thinking education and further identity discovery.

My identities are complex. They could not, and should not, be reduced into a single one.

Reference:

Razack, S. (2002). Race, space, and the law. Toronto: Between the Lines.

Windwraith, A. (2014). Deconstructing the Language of Rape.

hooks, b. (2000). Feminism Is for Everybody: Passionate Politics.

Not so trivial

A few days ago, some members of the self-directed seminar and I went to the Gallery, the on-campus pub, to grab some dinner. Unbeknownst to us, there was a trivia night event going on in the Gallery. Upon finding out, we decided to partake in it on a whim.

Games of trivia have a special spot in my heart. In high school, I was part of the school’s trivia team, and our team placed first in BC as well as doing quite well in the national competition. Even before high school, I always enjoyed collecting factoids and having obscure skills. I busted out these interesting tidbits about whatever topics we were discussing or when there were awkward gaps in the conversation. In short, I was (and still am) “that kid” who had something to say about everything.

Over the years, I have met many trivia enthusiasts through competitions and other trivia events, not to mention that a couple of my best friends were in the same high school trivia team. I had always thought that trivia attracts a certain sort of people — “that kid” — but I could not articulate what these attributes were. I stopped playing trivia games competitively once I entered university, but I still occasionally went to the odd trivia nights at pubs or at school, thinking nothing much of them. This time was different, however. Maybe it was the company of my fellow students in the SDS on identity, maybe I was in a more reflective mood — for whatever reason, I started thinking more deeply about why trivia was such a big part of my, and apparently of many others’, identity.

I think my affinity for “useless” knowledge and obscure skills stems from my body. I am not, and have never been, a physically imposing person. Physical strength has never been, well, my strength. Instead, I claimed power through knowledge and intelligence. I suspect that trivia attracts a certain type of person because its main function is to assert intellectual power; knowing small facts about subjects signals that my knowledge is so wide-reaching that it covers the realm of common knowledge and overflows into details that, surely, only a master of the subject would be aware of. Games of trivia, especially, are usually set in public arenas, such as tournaments, TV shows, or pubs. Only in games of trivia can you be a smartass in front of crowds of strangers.

This realization about trivia helped me think about the various different ways in which I exercise power. Atkinson talks about contemporary men doing “Pastiche Masculinity” — adapting to the death of traditional masculinity by creating multiple identities with various ways of claiming power. Surely staking a claim on power by knowing many “facts” is positivistic and based on Enlightenment ideas of rationality and objective truths. In order to overcome this, I must hold myself back from correcting others in abrasive ways, and consider different ways of knowing.

The Path to an Established Career in Medicine

In my previous post, I talked about going on a tour in a local hospital led by two medical residents (Ken and Jeff) and put together by an undergraduate club at UBC. I explained my interest in a career as a physician and then briefly mentioned the themes of structure, agency, and autonomy, using an example from the tour. In this blog post, I would like to write about the process to an established career in medicine in relations to two of the aforementioned themes: structure and agency and using my favourite reading (The Sociological Imagination) from our seminar this semester to analyze my thoughts.

Photo: midwifery.ubc.ca

Photo: midwifery.ubc.ca

Working 70-80hrs/week

A recurrent topic that both Ken and Jeff brought up was having 70-80 hour work weeks. As residents they work 70-80 hours per week with a possibility of having additional hour devoted to research work which may add up to a 100-hr work week. As a response, I tried to challenge them with the question, “How do you keep yourself healthy while trying to keep others healthy?” It just didn’t make sense to me that the job of medical residents and doctors is to keep people healthy and cure patients, but while they’re doing that, they’re asked to work 70-80 hour weeks, to work on-call, to work overnight, to do all-nighters, to skimp on sleep….. In response, Jeff described to us times that he would not have worked-out (exercised) for months and that he hasn’t cooked his own food in three months. He told us that it is important to be adaptable because this is just something that you “adapt to.” He then dubbed this work-life style an “old system.”

Relocating to rural areas to work

Jeff talked to us about his desire to work in the northern areas of BC, such as Kamloops, after he completes his residency. My question, of course, was “why?” From what I heard, his biggest reason for working in the interior is for the work variety and calmer lifestyle that it would provide. Whereas in a big hospital in the metropolitan areas there are different doctors working in different units, instead, working in the rural areas would mean that one doctor could be moving across all units and following all the patients. He also mentioned that there are “more things you can do” and “it’s easier to do things.” By that, I think he meant that the system is less bureaucratic and more flexible, hence easier to navigate, work around, and to do things.

Working in a big hospital

Ken on the other hand, gives off a more ambitious and driven sense of character, and is firm about working in big hospitals. His two main reasons for doing so are: (1) he wants to deal with kids who are super sick (these residents are pediatricians) and (2) he is really keen on the academic side of things and doing research — big hospitals and big cities would have the resources to assist him with grant-writing and open up to him a network of people relevant to his research work.

Tips for Applying to Medical School

A big question that we had as a group was about the process of applying to medical school. On this topic, Jeff and Ken had similar insights. Both of them agreed that you need to “jump hoops” and “play the game.” They say that the admissions process is to find the right people. Here are a list of inspiring messages I got from them:

- be honest, genuine, and straight-forward

- don’t contrive / blow-up or magnify your work and/or accomplishments

- “If you’re in it [going to medical school] for the right reasons, it’ll show [in your interviews]”

- be excited

- be yourself!

Jeff also told us about how we wasn’t like most of the other medical students who were overachievers to begin with. However, after being in medical school he started following the “culture” and tried to do many things too – trying to “find his place in the world,” but he ultimately burn out. With that, he leaves us with some life advice:

–-> “Don’t sacrifice your happiness for your future”

Photo: newcw.phsa.ca

Photo: newcw.phsa.ca

This reflection makes me think about a quote from C. Wright Mills: “The first fruit of this imagination – and the first lesson of the social science that embodies it – is the idea that the individual can understand her own experience and gauge her own fate only by locating herself within her period, that she can know her own chances in life only by becoming aware of those of all individuals in her circumstances”

Throughout the three four examples I gave above, I see strong interlinks between structure and agency. In the quote above and in Mill’s (1959) The Sociological Imagination, he discusses how people are living and making choices under the influence of the current time period and organizational structures. Working 70-80 hour weeks – is it really a choice? Relocating to rural areas – is it really a choice? Working in a big hospital – is it really a choice? Or are these “semi-choices” or “choices under circumstances” Why must we “jump through hoops” and “play the game” in order to get into medical school? What are these “hoops”? What is this “game”? These are all questions that, I pose to the reader, you – to think about, discuss, and answer.

And the question for myself – who am I, this person who wants to do what to get where [medical school, a career in medicine]?

Reference: Mills, C. W. (1959). The sociological imagination. Oxford University Press.

Construction of a space: My experience at UBC Improv show

I really like improvs.

Improvs are comedy shows with no script provided, where actors perform their acts by improvising on the spot.

My first experience of watching an improv show was in elementary, where a group of famous improv team visited our school to perform. The experience was mind blowing and since then, I became very interested in the subject. When I was in first year at UBC, I remember watching UBC Improv at our residence, as part of the first week program. I also went to their weekly improv shows, hosted at the Neville Scarfe building. And last Friday, I visited the site again, as an excuse for my blog assignment.

The room was filled with people and laughter was spread out through the room. Once again, I was amazed by how clever these actors were, as they related their skit to themes thrown out by the audience, built and changed their identities according to the situation and concluded by bringing together all the odd and irrelevant characters and situations to one plot. Their characters, use of language and action were rewarded by laughter and applause from the audience. The audience themselves seemed to be very energetic and engaged. What was significant though, was how this space was created.

In Razack’s article, “Race, Space, and the Law: Unsettling a White Settler Society”, she investigates how bodies are produced in spaces and how spaces are produced by bodies, based on Henri Lefebvre’s concept of space as a social product, where appropriate places to social relations are assigned, which could be served as a tool of thought and action, and as means of production, control and power.

I knew that Scarfe 100, where UBC Improv took place, was a social space because it was constructed by actors and audience who seeked for this space. The space was not randomly created but seeked by students, adults, friends of actors, and others who understood the language, understood the culture, therefore, understood the humour. I was interested in how this space was produced and how this space could influence bodies like the actors and myself, performing and watching the show.

As the show preceded, I realized that it was the actors’ efforts that created the space of engagement and acceptance. In situations where actors blanked out, other actors would immediately jump in to improve the situation or laugh at each other to promote laughter from the audience. Engagement from the audience were encouraged by actors as they would challenge the audience with statements like “I can’t hear you!” And by waiting for appropriate themes to be shouted out. I know I am not usually an outgoing person, but I found myself quite actively engaged in the performance.

The identity of this space is also uniquely constructed. What attracts people to watch improv shows is the notion that anything can happen in these shows. Basically, anything out of the norm in society is the norm within Improv shows. Gender switches, talking animals, illuminati invasion are all commonly played out. Comedy shows like improv are also one of the few spaces where social taboos and political injustices can be performed without serious consequences. This is because of the notion that comedy shows are performed solely for humour purposes and not to be taken seriously. I mean, can you really arrest a comedian? This gives power to comedians to challenge existing social inequalities in a seemingly light hearted, comical way. Historically, comedy shows were used by the powerless of society to voice their opinions, to influence and educate communities, on these social taboos and political injustices.

This reinforces Lefebvre’s idea that spaces are socially constructed, served as a tool of thought and action, and empower the users of the space.

However, because of this notion, there is definitely a burden on the actors’ shoulders. Improv actors are expected to be creative and funny while managing through a fine line of appropriate/inappropriate social taboos. They are encouraged to include social taboos in their acts but must be aware of the negative reactions when it is taken too far. For example, a white guy at the show provoked a lot of laughter from his character of being an ignorant American who always orders burgers at a Mexican restaurant. However, I believe this reaction would have been different if the same guy played the American who orders black people to serve him burgers. Since there is no script provided, every actor becomes responsible for their act.

Nevertheless, I have always been a big fan of improv and I encourage you guys to take part in the improv workshops, hosted by UBC Improv, as you will experience creating a small social space of your own, from attending to acting your own skit.

References:

Lefebvre, Henri, The Production of Space, Blackwell, 1991

Razack, Sherene, Race, Space, and the Law: Unmapping a White Settler Society, Between the Lines, 2002

Imagine Day and Volunteer Opportunities

Imagine Day is the largest on campus orientation day in Canada, welcoming over 8000 new students to the UBC Campus. It is held annually on the Tuesday following Labour Day Weekend; this year it was on September 2nd. The purpose of Imagine Day is to orient students and get them acquainted on campus through tours lead by current UBC students. What follows is a pep rally that hypes students for the upcoming year to start a new chapter in their life for university. The final portion of Imagine Day is the ‘Main Event,’ which is held on Main Mall Street. where all of the UBC clubs are set up on tables for students to explore their options to get involved on campus.

For Imagine Day, I was not a participant, but a Squad Leader. A Squad Leader manages the Orientation Leaders who have a group of new to UBC students to lead around campus throughout the day. As a Squad Leader, my role was taken up the January before Imagine Day to recruit and train Orientation Leaders for September. On Imagine Day itself, I was a trouble-shooter who ensured transitions of the Imagine Day itinerary ran smoothly, a helper for the logistical aspects of Imagine Day, and I ensured that my group of Orientation Leaders had everything they needed for the day.

Imagine Day, for many students, is a new beginning and a mark of a new chapter of their life. However, for this paper, I will focus on my experience as being a Squad Leader. My experience as a Squad Leader was not great in terms of communication with the Orientation Staff. My group of Orientation Leaders was great and we got along well, but it was my experience in my role that I did not like. I don’t feel as if I learned anything new as my time as Squad Leader. Therefore, it made me wonder why I wanted to join in the first place. It was because I wanted more leadership experience. As mentioned in one of my previous blogs, I plan for the future and jump at opportunities that can help better my chances in getting a job. I thought that applying for the Squad Leader position would help me gain some more leadership opportunities on campus and help me expand my networks. However, I didn’t feel like I learned anything significant. It made me reassess my motives. Did I just apply for the sake of the job title? Am I only doing this because I feel like I’m doing something productive for myself?

To further answer my questions, I draw upon the Forbes article that speaks about paid and unpaid internships and their benefits. It discusses the individual’s choice in getting and benefitting from an internship, whether or not it is paid or unpaid. The conclusion of the article is that “ultimately, the decision of accepting an internship is an individual’s choice made on its expected benefit” and that there should be no government interference on whether or not internships should be paid. Similarly, the Squad Leader position was like an internship in the sense that I thought I would gain from the experience.

To answer my questions above, it would be yes, I am because I’m trying to build my reputation of being an involved UBC student. I want to show that I am a hard-working individual that is involved in various ways within the UBC community. But it is through the structures placed upon me, such as the current state of the job market, which motivates me to be involved and to take on numerous opportunities on campus. My role as Squad Leader was probably very helpful in the logistical side of Imagine Day, but the job description made it seem like I would be doing and gaining much more. In the end of the day, the reputation of the Squad Leader role as prestigious is what made me apply, rather than the actual duties (which is a little embarrassing).

Autonomy in the Medical Profession?

This drizzly afternoon, I rushed to the bus loop from class in order to make it to a tour of a local hospital put together by a student-run club at UBC whose mandate is to help students in their process of pursuing a certain health profession.

We were met by two residents (graduated medical school students who have begun practicing in hospitals/clinics) at the lobby of the hospital. Both residents are males in their fourth year of residency — one had a staff identification badge hang down his t-shirt whereas the other had a stethoscope around his neck and was dressed in a neatly pressed dress shirt. Let’s call the former Jeff and the latter Ken.

In the past year and a half, after hurdles and hurdles of career choice challenges and changes, I developed an interest in becoming a doctor. There are various reasons why I think may be a suitable career choice for me (without thinking about my uncertainty of my capabilities in the natural and physical sciences for now). Amongst the passion of directly help people, the excitement for science, the ability to earn a living wage, and the respect, a big draw for me was the autonomy I perceived that a career in medicine would entail. To put it into picture, I have been (day)dreaming about how nice it would be to be a family physician/GP and be able to focus my time, attention, and efforts on helping patients without having to worry too much about living up to the expectations of supervisors, following bureaucratic rules, and navigating professional relationships with co-workers.

Hearing from the residents today made me feel a little grey as while Jeff was showing us around and telling us about his experiences in medical school and being a resident at the hospital, these words he spoke jumped at me:

- protocol

- procedures

- divided

- paperwork

- culture

- process

- system

- adaptable

- protected time

These are all words that I would say can be related to bureaucracy and more pertaining to your class theme, structure versus agency. Jeff used the word “protocol” when he showed us around the maternal care room. In the maternal care room, there is an apparatus that you use to revive a newborn when he/she stops breathing (please excuse my faulty explanation). When he explained this to us he pointed to the poster on the wall which states the protocol, or what procedures the doctor should follow in such an event. He said to us something along the lines of, “It’s here because you won’t have time to think, they just want you to follow the instructions and just do.”

In my next blog post, I will expand on my thoughts about agency, structure, and the process to a career in a medicine.

Re-wording Kimmel’s Guyland: Institutionalized Masculinity for a Grade 7 Student

Every Monday morning, I get up early before attending our Sociology seminar class on Student Identity, to volunteer at my elementary school as a teacher’s assistant for my grade 7 teacher. Ever since I had started this volunteering position in October, I have recognized interersting things about the boy students in the class, throughout my two hours spent there.

My experiences in the past two months have been pleasurable and intellectually stimulating, simply by observing the classroom dynamics. During class time, I often witness the boys to be the students who are always tireless, vibrant, and the most spirited. In addition, the majority of the male students would also often raise their hands quickly to respond when the teacher poses a quesiton to the class. Moreover, it is often the boys who volunteer to assist the teacher move boxes around in the kitchen or to help transport some heavy textbooks from the library back to the class.

Moreover, in the two months, I could see the feelings spurring between a female student and a male student. From across the classroom, I can see them eyeing each other while the teacher lectures in front of the classroom. At worktime, as the girl works on her homework, the boy would take glimpses at her numerous times, and once the girl looks over, he quickly retrieves his glance. This would be the same for the girl as well. For instance, there was a time where the boy would get up from his seat to throw out a piece of garbage, the girl would pop her head up, as though she felt his moving presence. I could see that her eyes were following him. But once he turns around and walks back towards his seat, the girl would quickly look back down to her social studies homework. Talk about classroom romance!

From this, it is extremely interesting to me as it relates to Kimmel’s “Guyland” notion of Masculinity. His idea is rooted from the perspective that masculnity is socially constructed. Similar to the boys in the classroom at the elementary school, they reinforce what it “means” to be a “real man”. Clearly, it is suggested through their actions of carrying heavy objects and initiating to help the teacher out. Thus, these characteristics underline the masculine stereotypes: will-power and strength of men and that men are made to be team players. Kimmel describes that Guyland as a period between adolescence and adulthood (16 years old to around mid-20s). However in the case of this, the students are 13 year old gr 7 boys. As a result, Guyland doesn’t appear within a limited timeframe. In reality, it exists prior to 16 years old and is fluid between age groups.

In addtion, what I find also interesting is that there may be an aspect such that the boys in the class are complying to the masculine touches, in order to portray to the ladies that they have what it takes to be “the man”, or to be “manly”. In the case of the crush between the girl and boy, that specific boy more often than not that is the one who would raise his hand up to speak, the one who volunteers to participate in completing math questions on the whiteboard, as well, the one who offers to carry the heavy world atlases from classroom to classroom. Moreover, it is at this point that I recognize that he is unaware of the implications of following such traits. Because masculinity is socially construcuted and is imposed on him, he does not struggle with his true identity and who he really is in an attempt to make themselves look “masculine” because he only sees manliness as the way to go. In other words, because individuals are born and brought up with the image of masculinity, we do not realize that we are following what society has created. In this case, the male student does what he does without his acknowledgement that he is complying to the social order and therefore, doesn’t realize the struggles of fitting into that category.

In contrary, our belief of masculinity is understood by the ladies as well. From what I see between the classroom lovebirds, I believe that it is due to the boy’s behaviors of masculinity, in which the girl is attracted to. With the boy taking the initiatives to respond to questions and hauling heavy boxes in and out, it shows that he is a team player and that he is powerful. Through this, with the help of social media today that reinforces the image of masculinity, the girl sees his actions as right and fitted, thus, increasing her liking towards him. As we can see, as Kimmel states that Guyland typically occurs at the age of 16, boys in fact adhere to this masculine ideal at an earlier age.

Alternatively, Kimmel raises that men also adhere to the “Bro Code” in which “a man’s ‘brothers’ are his real soul mates, his real life-partners.” In relation to thinking about the male students in the class, they often hang out together as a pack in order to, I would say, to put more emphasis on their “coolness” or tough mascunline traits. With this, it allows them to impose power among their other male counterparts in their class. In this case, this reinforce is created by their social in-group behaviors, without thinking the contrary, that can be seen as struggles.

Once again, it is because of the normality of what is means to be masculine, that these kids see these traits as the norm. Due to this idea, these elementary school student’s identities are standardized through the trope of what is means to be masculine by influences of the media and their friends. However in relation to me as an univeristy student majoring in Sociology, my ideas of such social constructions have been unpacked, therefore, I understand more of the truth that lies underneath the social beliefs. From this experience volunteering, I wonder every Monday how my identity would change if I were to just follow such constructions imposed by the world. In other words, how would my life be if I only followed what ‘femininity’ meant in society without the opporunities of being powerful and spirited, like the gr 7 student?

References:

Kimmel, M. (2008). Guyland: The Perilous World Where Boys Become Men.

One Soup Night, Two Identities: Making Sense of my Musings at a UBC Event

In this blog post, I plan to write about an event that I went to at the residence that I live at on campus, my discomfort at the event, and my musings on why this was so. I will bring in aspects of Du Bois (1903/2012) to help with my understandings.

I have had the opportunity to live on campus for the duration of my undergraduate degree—well for eight months at a time anyway since I live at my family’s home in Surrey during the summers. In my first year, I lived at a UBC first year residence in a double room with a close friend from high school. In my second year, I applied for UBC residence and did not get in, so I looked into other options for housing and resigned myself to finding somewhere to live off-campus if nothing panned out. I ended up applying to another residence at St. Andrew’s Hall. St. Andrew’s is where the College of the Presbyterian Church is located at UBC as well as residences for students of the college in addition to UBC students.

I lived at St. Andrew’s during my second, third, and now in my fourth year. On their website, St. Andrew’s writes:

The sense of community is important at St. Andrew’s Hall. Not only students studying for ministry within The Presbyterian Church in Canada but all residents are encouraged to bring their gifts to the community and to make use of opportunities for intellectual, physical, social, and spiritual growth.

In my (going-on) three years living at St. Andrew’s, I have received email upon email of events hosted by St. Andrew’s for its residents and community members to attend. It was only this year that I actually went to one of them—in part because I have a roommate who is a Community Coordinator at St. Andrew’s (similar to the role of a Residence Advisor at UBC residences) and so she is very vocal to encourage all of us in our apartment to attend upcoming events. This particular event was a Soup Night. Every Wednesday, St. Andrew’s hosts a Soup Night in their chapel, followed by an “Open Table” discussion on a different religious or spiritual topic of the week, led by one of St. Andrew’s chaplains. I get an email about Soup Night and the Open Table discussion every week to remind me that there is yet another one to be hosted, telling me what kind of soup will be given out and what the topic will be. This time around, there was organic red lentil soup to be had and “world salvation” to be discussed.

I had never been in the chapel at St. Andrew’s before, but I have walked past it many times, so I knew where to go. When I entered the chapel with my bowl and a spoon, I noticed that there were some differences between it and the churches that I had been in before. It was basically a big room with really high ceiling, there was a big cross on the wall, a wooden podium at the front and some regular chairs (not pews) as well as some couches. It looked as though the room functioned for many uses so the chairs and couches being mobile helped to re-organize easily. There were also some small tables and on them sat some pots. I figured that since the objective of the Soup Night was soup, I should head towards that. The pots seemed promising, so I gravitated towards them. I was greeted by a couple people who were standing by the pots. They told me to help myself to some soup. I did. Then I stayed for a little while and made small talk with them. They asked me whereabouts in St. Andrew’s I was living, what I was studying, etc. They also asked me if I would be staying for the Open Table discussion. At this point, I made a snap decision not to go to the discussion and told them that I couldn’t stay because I had something for class due the next day that I needed to get done. That part… was a lie. I didn’t have anything due the next day.

I had decided that I had become too uncomfortable being in the chapel and would not be comfortable going to the Open Table discussion within this setting. Although the Soup Night and the Open Table discussion was advertised as being open to everyone to attend, no matter their cultural, ethnic, or religious background, I was very intimidated to partake in it. I left the chapel soon after and went back to my apartment thinking about my discomfort.

Why did I feel uncomfortable? I had been to church before, especially when I was younger. My mom is Anglican and, when I was younger, she would send my sisters and I to Sunday school while she went to Sunday mass. My sisters and I stopped going to church regularly when we got older, but my mom still went by herself or with my aunts on occasion. For the most part, I only go now if my mom wants some company on special occasions such as Christmas Eve mass. However, our family still celebrates Christian holidays (Christmas and Easter) at home. Thinking back to my familiarity in my childhood with the church, I didn’t fully understand why I felt so uncomfortable in the chapel at Soup Night until I thought on it further.

Du Bois (1903/2012) speaks about the veil, double consciousness, and two-ness in The Souls of Black Folk. He writes on the veil as a metaphor for oneself being “wrapped in”. So long as one is wrapped in the veil, they will always see the image of themselves reflected back at them as how others believe them to be, allowing others to erase their two identities. The veil affects a person when the person internalizes this erasure of their two identities. When one transcends the veil, they can begin the process of juggling their two identities and their double consciousness. This two-ness of identification is something that I struggle with.

While my mom’s influence in my life meant that I was familiar with the church in my childhood, my dad’s influence in my life meant that I was also familiar with Islam. My family on my mom’s side are European, Caucasian, and Christian and my family on my dad’s side are North African, Berber, and Muslim. The two sides of my family have contributed to my sense of two identities, two cultures, two ethnicities, and two heritages. Growing up in a mixed household and with a mixed family, I embody a two-ness and a type of double consciousness. Although Du Bois writes specifically about his own double identity being American and African in a specific context—during the late 1800s/early 1900s, a time of social and political turmoil for African Americans, the beginnings of the Reconstruction Era of the American Constitution, and the emancipation of African American slaves in the South—my two-ness identification is markedly different from his.

Now, I don’t exactly identify as Christian myself, nor do I identify as Muslim, but these religious backgrounds cannot be isolated as purely religious identifications—in my mind, there is a distinctive cultural and ethnic component to claiming either. That is to say, there are different cultural and ethnic interpretations of Christianity and Islam (e.g. Muslims in Pakistan are influenced by a different set of cultural/ethnic backgrounds than Muslims in North Africa) and that both religiosity and culture/ethnicity feed into each other. So, as I thought about why I was uncomfortable at the Soup Night and wondered why I was uncomfortable since I had been in a Christian chapel many times in my life before, I realized that it was not just the religious aspect that I spurred my discomfort. It was also the cultural/ethnic aspects that had me uncomfortable and the idea that my two-ness might be erased by the other Soup Night-goers.

Those instances in which I had experienced the church had previously been with my mom and/or my sisters, who understood my two-ness. Previously, it had been enough to have someone at my side who knew my two-ness and, at Soup Night, no one knew of my two-ness and it would require that I attempt to explain it. Perhaps at this point you’re thinking to yourself, “You shouldn’t feel required to explain your two-ness to anyone, Krystal. That’s a personal thing and so divulging it is not a requirement if you don’t want to.” But that simply isn’t true. If you gave me a nickel every time someone asked me “what are you?” or “what’s your ethnic background?” or “where is your last name from?” I would be a decently wealthy person. These sorts of questions and speculations on my identity from others in the past, in a way, have coloured how I have internalized an obligation to let others know, since those questions have always framed to me that they are obligated an answer. For this, I feel that Du Bois falls a little short on the topic of two-ness. For me, my two-ness is largely framed by how I feel the obligation to communicate it to others because, if I don’t, they will understand me as one identity and I would feel almost like a fraud to go along with it because it is not the whole picture of who I am. Yes, Du Bois hits on some really important points regarding how a person internalizes their two-ness, but his understanding of this internalization as a linear progression (being wrapped in the veil → transcending the veil → having a double conscious/internalizing two-ness) is a short-falling of his piece. Two-ness is not static and I find myself negotiating (and re-negotiating) my two-ness differently depending on the setting and those around me.

References

Du Bois, W.E.B. (2012). The Souls of Black Folk. In S. Appelrouth & L. Desfor Edles (Eds.), Classical and Contemporary Sociological Theory (2nd ed., pp. 271-283). Thousand Oaks, California, USA: Pine Forge Press. (Original work published in 1903)