Hey! Here is the direct link to our mapping project:

Author Archives: Marianne Wu

A Reflection on Reflection 對反思的反思

My identities are complex. They keep changing and shifting focuses depending on context. And They should always be intersectional.

“my feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit.” – Flavia Dzodan

Reading this quote on Facebook today made me think of my positionality in relation to the #Ferguson issue. The jury officially announce that the white male police, Darren Wilson, face no charge shooting 18-year-old black citizen Michael Brown to death on August 9th in Ferguson, Missouri, United States. Started from Ferguson, a city with a large black community, solidarity events and protests spread over the U.S. and some parts of the world, many tagged as #BlackLivesMatter. Learning from Alice Goffman’s lecture earlier this semester that in low-income black communities, young men have to face policing, arresting, and killing in their everyday life in the U.S., I do not just see the shooting and the jury decision as a single issue but a systematic problem that put the African-American ethnic groups in fundamental disadvantage and injustice.

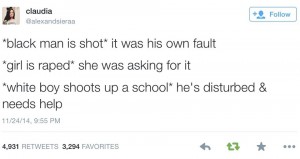

Why does this disturb me and why it is relevant to me? Because in this context I quickly see myself as a person of colour in a white-settler society (Razak, 2002) that is established upon white privilege. At the same time, along the line of Razak’s intesectional approach to space, gender, and race, I am aware that my position as an ally with the #BlackLivesMatter protest is not simply related to my skin colour, but a self that intersects with multi-dimensional identities such as in ethnicity, gender, and social location. To expand my thoughts I think it is good to start with this tweet:

[first, let me try to type in my thoughts in Chinese]

這幾行字簡約卻充滿爆炸性,因為其啓發我將種族和性別不公聯繫在一起。這在我看來,也是交織性女權主義的魅力。

[Then, I translate them into English]

These few lines are simple but explosive, since they push me to further see ethnic and gender oppression together (in a white-dominated patriarchal system). To me, this is the charm of intersectional feminism.

[as I learn sociology through an English-speaking education, I soon run out of words in Chinese and return my reflection to the English thinking mode]

To be sure, paralleling the experience of the “black man” and “girl” in contrast to the experience of the “white boy” does not mean that we should draw an equation mark between the two. My experience being a Chinese woman is very different from that of a black man. But the experiences of the blamed and the redeemed connect me to the movement of black people’s rights.

When I was taking SOCI 101 sociological theories in another university, I was confused about the feminist theory because I saw it as a combination of all kinds of social justice arguments. To be honest, I was not impressed at all and I came to resist the “feminism” label. I had negative feeling towards feminism as feminists make claims over almost every issue on injustice. To simply put, I was tired of seeing the label “feminism” everywhere. At the same time, “feminism” was a term that I often associated with the images of radical men-haters and naked FEMEN.

But now, when I am reflecting on how I have been reflecting on feminism during these few months, I see the value of feminism that intersects every social components together. Which means, nothing should be explained merely by race, gender, or class, etc. — it should be explained with these all together.

I first heard of the term “intersectionality” from the courses offered by the UBC Gender, Race, Sexuality, Justice program. I got to talk about it further through learning about it in some public lectures, and interacting with my friends who self-identified as feminists (mostly male!). This semester is very special to me in terms of the process of feminist self-realization. I never publicly claimed to be a feminist until I take SOCI433, which provides me with an intersectional approach to see my identities and other’s identities. The classroom goes beyond the physical space into the virtual space (Facebook group) of public discourses, and allows me discuss feminist topics and issues such as Emma Watson’s UN speech and rape cultural on UBC campus with friends and classmates. More importantly, throughout reading feminist writings by Azaia, bell hooks, and Beckie, I realize that feminism is a way of thinking of the world intersectionally, and acknowledging our own limited but international perspectives. For example, early in Azaia’s thesis, she acknowledges that her writing comes from a perspective of a white urban working-class female (2014, p. 20). In bell hooks writing, she also make it clear of her positionality as a black female.

After all, in this post I touched lots of bits and pieces of my identities. You may think there is no “theme” or a major theory. But this is exactly my point. In this post I try to briefly show you how my identities are intersected:

- my gender intersects with my ethnicity, which make me an ally of the #BlackLivesMatter;

- Chinese as my first language (everyday, reflective) intersect with English as my second language (academic, critical, reasoning)

- my past perception of feminism intersects with my current experiences of feminism.

- my social position as a UBC sociology student intersects with my gender, class, race, and other identities, which provide me with resource and access to critical-thinking education and further identity discovery.

My identities are complex. They could not, and should not, be reduced into a single one.

Reference:

Razack, S. (2002). Race, space, and the law. Toronto: Between the Lines.

Windwraith, A. (2014). Deconstructing the Language of Rape.

hooks, b. (2000). Feminism Is for Everybody: Passionate Politics.

Share: The Spatial Politics of the Occupy Central 佔領區的空間政治

Translated by Marianne. Written by Xueying He 何雪瑩. Saturday, November 11, 2014.

The Occupy Movement in Hong Kong has lasted for a month and a half. The three Occupy Central leaders claimed that they would confess to the police someday. Students organizations like the Hong Kong Federation of Students and the Scholarism believed that they could not retreat without any desirable outcomes. These show that everyone has a rather similar view towards the Occupy Central: the three leaders think that civil disobedience is the core of the movement, so the movement could not reach an end unless they confront the judicial process; the two student unions think that the movement is the means to the negotiation of political reform. However, how is the Occupy Central different from other social movements? Although a tough question, I would like to start my answer with the function of space, through the perspective of urban geography.

佔領持續接近個半月,佔中三子強調有天他們會主動自首,學聯和學民認為未有任何成果難以撤離。這說明了各人對佔中的想像非不一樣:三子認為公民抗命是佔領運動的核心,必須完成自首和面對司法程序整個運動才告圓滿;雙學大致上認為佔領是政改談判的籌碼。然而佔領跟其他社會形式的社會運動有何分別? 這個問題不好回答,但從城市研究或地理學而言,起點必然是空間的作用。

We are surprised by the booming study rooms, the colourful comment walls, the concrete flower garden, and the tents everywhere on the highway; we are attracted by the surreal scenes that appear in Hong Kong for the first time. These scenes are possible through the interaction of space and time. The typical organized political involvements such as voting and council meeting occupy very limited time and space, and most of the recent political engagements and social movements occurred in the virtual space. This is not to deny the importance of the time-space-constraint political engagements, in fact these forms are the also the necessary components of this Occupy Movement. But the Occupy Hong Kong reflects the infinite possibility of occupying a physical space for a longer period of time.

我們對瘋狂生長的自修室、五彩斑斕的連儂牆、水泥地上種花、幹道上遍地盛開的帳篷驚喜,為香港首次出現如斯虛幻的畫面着迷,事實上這些景點得以發生,是空間和時間兩者互相交織而成。一般體制式的政治參與如投票、諮詢會議等所佔據的時間和空間都相當有限,近年矚目的網上政治參與和社會運動更是發生在虛擬空間。這不是說時間和空間有限的政治參與不重要,實際上以上的政治參與和社會運動都是這場佔領運動得以發生所不可或缺的條件。然而今天的佔領之所以如此撼動人心,甚至超越其他社會運動,正反映出長持續一段時間佔領物理空間所孕育的無限可能性。這也許是其他形式的社會運動無法比擬的。

Surrealism of Walking across the Flyovers

游走於行車天橋的超現實

數周前我在「流動民主教室」曾經提起,能在幹道上蹓躂是多麼surreal的事,有位中年男子立刻走過來對我這種「佔領幹道」的正面思想表達不滿。今天用雙腳在金鐘的行車天橋上游走,我仍對眼前的景象有多超真實感到不可思議。這的確不是我們使用空間的習慣。試試閉上眼回想佔領或罷課前的金鐘長什麼樣子。那是一座恍如堡壘般,被圍起(fortified)和升高(elevated)的政府機關。人們要過去多從金鐘地鐵站出發,穿過海富中心,上電梯,經天橋到達「門常開」。由地底(地鐵)經天橋到離地升高的政府總部,整個過程完全沒有「腳踏實地」,也沒有停留的理由和時刻,因為它僅僅是一條通道,讓行人行來行往,什麼事都沒有發生。

而分隔中信大廈和立法會出入口的馬路,仔細想想,我們何時開始得知那條叫「添美道」?答案很可能是2012年的反國教運動。後來今年夏天的新界東北,還有今次的佔領運動,添美道再成主角。在非「社運進行中」之時,你會記得添美道嗎?又有多少人會在添美道流連忘返?

添美道、龍和道這些地方,令我想起法國人類學家Marc Auge筆下的non-place。先別管他本來的理論是non-place是超現代性(supermodernity)的產物而超現代性又是什麼,這些non-place的特性是沒有任何人際社會關係、身分和歷史性的地方,他筆下的例子包括機場、公路和超級市場。其他在政總短暫發生過的社會運動都曾暫時將添美道、龍和道、夏慤道這些non-place改變,為其賦予社會關係、身分和歷史意義,而眼下的佔領運動更是「2.0」加強版。

Commercial Center Becomes Living Areas

Before the Occupy, the Admiralty was a political and economic center. Such a non-space was not designed for a long stay, nor for attracting people to stay. Yet this movement is able to continue, with thousands of people staying over nights and millions of people mobilize during off-work periods, not only because the occupiers have strong beliefs in democracy, but also because this emotionless commercial centre has become suitable for long term stay and even living. This process is placemaking.

商業中心變成生活場所

本來金鐘是個政治和商業中心,non-place空間設計從不宜久留,也不打算吸引人久留,結果這場運動得以一直延續下去,長期有上千人在晚上過夜,放工時間有上萬人在流動,固然因為佔領者對爭取民主的理念非常堅持,同時也因為這個冷冰冰的商業中心變得適合長時間逗留,甚至棲息和生活。這個過程正是地方營造(placemaking)。

In other words, because citizens are most clear about the need of their communities (the best example, again, is the location of the stair handles), they do not need bureaucracy to decide the use of every inch of the land….. During a movement, with enough time and physical space,

換句話說,正因為市民本身才最知道社區的需要(最佳例子再一次是扶手樓梯的位置),他們不需要官僚以上帝視角決定每吋土地的用途。當關心空間使用的團體和個人多年來辦研討會寫文,建議釋放官僚對公共空間的限制之餘,也希望擴闊市民對空間規劃和使用的想像時,原來只要一場佔領發生,有着足夠的時間和物理空間,人的潛能就這樣釋放出來。基本的地方營造原來可以咁簡單。而當沒有了不准踢足球不准玩滑板等為怕發生任何意外等的外來規定,市民自己會學習跟別人從實踐中討論空間使用的法則和規矩。當中難免會有些衝突,例如點解你紮個營阻住我個營出入,但這也是學習的一種,而且外來規定引發的衝突、不快和風險,往往不比自發狀態少。

城市屬於使用者不屬於地主

更基本的是,佔領運動要爭取的不止是真普選、廢除功能組別和市民有免受不合理警察暴力自由這些公民及政治權利,它愈來愈關乎爭取城市權(Right to the city)。法國哲學家拉斐伏爾(Henri Lefebvre)於1960年代提出爭取城市權運動後,這場討論一直延伸至今天方興未艾,地理學者也開始將城市權的意義擴闊到無限大包括公民得以享有公共物品(public goods)如水電房屋的權利,如此使用城市權概念並沒有錯,但我們必須回到拉斐伏爾提出城市權的背景。他看不過眼的是在空間生產和使用的過程中,交易價值 (exchange value)取代了使用價值(used value)成為決定性原則。一塊地用來起樓還是起公園並非視乎能為市民帶來多大用處而是能賺幾多錢。為何今場佔領運動是一場關乎城市權的戰役,其實答案就在我們日常的修辭當中。佔領城市的主要幹道會令每人返工多30分鐘,經濟損失幾多億,商店損失又幾多億;換句話說,夏愨道應該是幹道而不是讓人佔領的建制和警方修辭正是空間的交易價值凌駕一切的明證。當我們每天為可能清場擔驚受怕,不就是因為我們使用道路和政府總部作為抗爭空間的城市權受威脅嗎?

可以幾肯定的是即使我們成功爭取公民和政治權利落實,城市權卻更難落實。一來城市權面對的不止是政治還資本的影響(全球民主國家爭取城市權的運動更是形形色色,可見民主並非萬靈丹),二來爭取城市權不是單單以獲取公共資源為目標,而是一場不曾止息和演化的運動。拉斐伏爾筆下的城市權可分為right to participation 和right to appropriation。前者比較容易理解,簡單可說是當空間改變所有受影響的城市人都該有權參與決定,而非限制於地主、屋主或股東本身;而right to appropriation更是一場阻止空間異化的行動。拉斐伏爾認為當空間的交易價值凌駕於使用價值,空間便會跟城市使用者發生異化,兩者關係割裂起來,只有通過空間的appropriation人們才能重奪空間,而非落入資本累積倫理之中。城市不屬於地主,而屬於使用者。拉斐伏爾同時提出將autogestion這個工人自己營運工廠的概念融入城市權之中,透過appropriate城市空間我們才能自我管理空間下的生活,將城市空間重新跟社會關係網絡重新連結起來,而非受資本累積邏輯決定城市生活。這,不正正是發生在今天的金鐘嗎?

當佔領運動由爭取政治公民權利延伸至城市權,而且因為物理空間和時間許可,以實踐而非一般倡議(advocacy)的形式爭取,這就是一種預兆式政治(prefigurative politics):佔領華爾街的精神領袖、人類學家David Graeber指出,佔領華爾街的預兆式政治的重點在於,我們要爭取一個理想,在運動間必先將其實踐出來。

香港佔領主幹道的獨特性

這場佔領運動將會在香港和世界近代史上佔上一席,理順空間在佔領運動的獨特角色將對我們理解其本地和國際重要性非常有幫助。國際上近年佔領運動如雨後春筍,由2010年英國學生佔領大學校園抗議瘋狂加學費、阿拉伯之春、佔領華爾街在全球遍地開花、2011至12年西班牙的Indignants Movement、去年土耳其伊斯坦堡,關於佔領的專著和研究從不缺少。當中雖然不少研究偏重互聯網的動員能力,但空間作為佔領運動最獨特的條件卻不容忽視,而且當人家大多數都是佔領廣場或公園,香港卻因沒有如此具公共價值的廣場加上誤打敵撞下佔領主要幹道和一堆附近零碎的non-place,這種香港的獨特性注定是要被仔細研究和記上一筆的。而我們在香港,當一些前輩都說運動陷入膠着狀態而要盡快退場,或者我們是要「佔領人心而非佔領馬路」,他們說的在社運的策點上都非常有道理。但如果將空間在佔領運動的獨特性包含在內,我欣賞到的倒是另一面:時間愈長,佔領區物理空間和在其之間發生的人際和社會活動和關係也在不停演變中,如此看來這個空間實驗每天都在經歷或大或小的改變,從來不曾陷入膠着狀態。「佔領人心,而非佔領馬路」,我非常明白爭取全港市民也很大程度上同意這樣的說法,但同時我也感到,只有透過佔領馬路,人心才會發生改變。

相片、文字來自:

http://news.mingpao.com/…/art…/20141109/s00005/1415471606437

Breaking A Norm

Time flies so fast without a hint. Our seminar is entering its second last week. For old time’s sake, I want to reflect on a little event that I created in this seminar at the beginning of the term.

I planned a norm-breaking experiment* with a friend, who was going to give a presentation to the SOCI 433 class with me. I told him that I want to break a norm by speaking Chinese in a class setting, and at the same time displaying important contents in Chinese, and he can do the same in Filipino, one of his mother tongues. (For those who are not familiar with the class, it is a student directed seminar on identity and structure. I am one of the four coordinators of this class. It has15 enrolled students, whose majors are sociology and political science; all of them are in second year level or higher. Every week, students attend two 1.5 hours classes, and one to three of them have to give a presentation on the assigned readings and facilitate a discussion afterwards.) Our presentation took place in the fourth class, when personal network was not well established between the presenters and the audience.

At the beginning of the presentation, I showed a PowerPoint slide with a rather long introduction of the reading and discussion contents in traditional Chinese. At the same time, I stood in front of the classroom, faced 14 colleagues, and talked in a serious tone about the contents in Mandarin for roughly one minute. Then my presentation partner at the back of the classroom began to speak fast in Filipino, with the long written Pilipino displayed in another PowerPoint slide. After that, we switch our language back to English. Before the class ended, we asked our colleagues to reflect on our behaviours and we debriefed on our experiment.

At first, I feel a little unprepared and uncomfortable, mainly because I had to start the presentation with Chinese. My nervousness affected my speech, making me unable to speak Mandarin as fluent as English. But as I continued talking, I came to an assumption that the contents were communicated to the audience, who remained silent but attentive. I somehow forgot the fact that all I said and displayed in Chinese would not be understood by the majority of the students. Later, when listening to my partner speaking a language that I am unfamiliar with, I was unable to capture any meaning, although I judged from the duration of the speech and the length of the written words that he was mentioning some important points.

Speaking in a non-English language in a sociology class was so unnatural that it seemed to be merely a performance. I had to control myself not to laugh at our pretentiousness. No one interrupted our speech or raised questions. When we finished this introduction, we suddenly spoke in English again, because we knew that English is the only language to sustain the operation of this class. At the end of the class, students reflected on our acts. A white female responded that at first, she expected us to translate what we said; then she came to question herself in her head why she should expect that. Another white female also reflected that she unexpected us to speak in non-English languages, but then she also realized that speaking English as a norm in universities is questionable.

By speaking non-English languages for a certain period of time without notifying my classmates, and acting as normal as I can, I intended to challenge other students’ expectation of receiving a presentation in English in a formal class setting. According to Neil Smelser, social norms are a set of mutual expectations of how to think and behave (as cited in Nick, 2002, p. 40). Their surprise would reflect that English is the normative language used in Vancouver’s higher education institutions like the UBC. Why is English the normative language at UBC? This question triggers a series of complex discussions about space, language, and identities of Vancouver. In brief, UBC is based on the unceded territory of the Musqueam community, but its official language is exclusively English, which reflects the white settler society’s identity control of communications and values over this public space.

As a Chinese, I share neither the indigenous identities nor the white settlers’ identities. Speaking my own language in a classroom, where communication in English is mutually expected, not only challenge the normalization of a white settler society’s language, but also challenge my legitimacy of speaking Chinese in public. Chinese characters and Mandarin represent my identities and values as a Chinese; they also represent knowledge and experiences that are required to understand the language. My location in the front of a classroom facing all students put me into a public space, and since I am one of the presenters, I became the center of the public discourse.

Occupying a foreign public space, being the central of focuses, and speaking in my mother tongue that few audience understood, make me a representative of a single unified identity and value as a Chinese. Yet as an individual actor in this experiment, I realized that communicating my Chinese identity and value to a public space outside China contains several barriers: the displacement of collective knowledge and experience relevant to China, the displacement of China’s cultural and political contexts, and the displacement of the audience that I can communicate.

* this experiment was part of the assignment of another sociology course that I enrolled in, which was a seminar on social movement.

Reference

Nick, C. (2002). Making Sense of Social Movements. McGraw-Hill International.

Seeking a Space, Performing a Space: Imagine Day at UBC

“On the first day of classes, campus is transformed and over 8000 new-to-UBC students and over 1000 faculty, student, and staff volunteers come together to welcome you to your new academic community and celebrate the start of the school year.” (Imagine UBC)

“The first-years are so unlucky, they get this cold and heavy rain on Imagine Day. Too bad for people at the booths. Who wants to be outside?” (talking with my friends)

Rain, rain, rain. As a featured outdoor event for new students (mostly first-year) to discover the student clubs and communities on campus, the Main Event seemed to have difficulties escaping the cold and heavy rain on the Main Mall on September 2, 2014.

Seeking a Space: Where is the Community I belong?

As a transfer student, that was my second school year at UBC, and naturally my second time being in the UBC Imagine Day. The Imagine Day description made I imagin that by connecting with the little space of a booth, I can later connect with a certain space on campus where I can call a community. This space could be a physical one (such as a club office or an event site) or/and an imagined one (such as a Facebook group, a friendship network), and it must be one where I feel comfortable revealing my identities (for example, a Chinese person) and behaving as myself. Yet my searching last year as one of the “new-to-UBC students“, I recall, did not lead to any fruitful outcomes. I signed up for the Meditation Community’s email list, but I had schedule conflict with all of their events; I paid $10 for the membership of CSSA (Chinese Students and Scholars Association) but found it useless; several clubs that I signed up didn’t even send me any newsletters. Besides, what UBC described as an “academic community” was largely absent in the Main Event, since nearly all the booths were presented by cultural, spiritual, and recreational clubs. Arts academic clubs, for instance, were told to present in the morning at Buchanan Courtyard, a space that was separated from where a wider audience located in the Main Event.

Wandering around the Main Mall among crowds of twenty-something-looking people, walking in and out among tents and booths, reading banners, signs and posters for information, writing down my name and email, talking or refusing to talk with others: I saw myself as one unit of complex identities attempting to build connections with other unites of identities. Using Sherene Razack’s concept of linking bodies with space in Race, Space, and the Law (2002):

“[T]he symbolic and the material work through each other to constitute a space” (pp. 8).

a space is not just an “innocent” space outlined by objects and people, it should be further analyzed as a social product (pp. 7). In other words, a space can be social, and its social meanings should be performed. In the searching of other spaces, bodies have to move, symbols and languages have to be shown, interpersonal interactions have to be performed (physically, verbally, emotionally). Occupying a bodily space in the Main Event, I saw myself entering, exiting, and re-entering different social spaces that were performed by groups of individuals with certain identities.

Performing a Space: A Chinese Community of What?

Redoing my searching this year, I tried to focus on one aspect that I was always interested in: the Chinese cultural clubs. Directly related to my identity as a Chinese student at UBC, I would like to use my perspective to briefly examine how a space is performed with social meanings. How do these clubs represent themselves? What kinds of space do they create at UBC?

1. A Space of Language

A space can perform its social identities through verbal and written languages. It was easy for me to identify most of the Chinese cultural clubs by looking for signs and banners, since many of these material spaces were presented through Chinese characters. Interestingly, since modern Chinese have two written forms, some of the signs were in traditional Chinese, which was officially used in Hong Kong and Taiwan; some were in the simplified one, which was officially used in mainland China. This language difference not only showed the culture that the clubs intended to present, but also showed what audience these clubs were presenting to. Occasionally, I also hear Mandarin and Cantonese communicated between students. Building instant identity connections, language performs symbolic meanings through the material spaces; it also reflected the diverse cultural identities within the “Chineseness” of the clubs.

[Language representation (top&middle: in traditional Chinese; bottom: in simplified Chinese).]

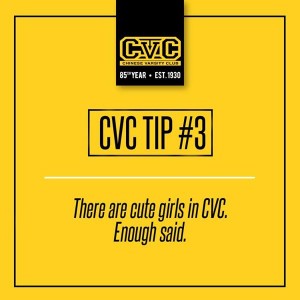

2. A Space of Racialization or/and Sexualization

Through asking questions to every Chinese cultural clubs I found, I noticed that the three most common events these clubs organize were parties, games, and ski trips. I imagined myself being in a club, a party room, and a Whistler hotel room, but I couldn’t imagine a conversation or a community. Once again, I found no way to seek an “academic community” among different Chinese cultural clubs. Moreover, I was shocked to hear some public announcements from two Chinese cultural clubs:

A male executive from one club spoke loudly to his surroundings: “….If you have yellow fever or Asian fever, this is the place for you.”

A male executive from another club said to the people who were passing by: “come for parties…… and get laid.”

Performing as representatives of their clubs, these two male executives presented their imagined community that I perceived as dangerous spaces. As a female I felt very uncomfortable with what these two particular clubs created within the public space of the Main Mall: the terms “yellow fever” and “get laid”, and the images (as show below) created a social spaces that was either racialized or sexualized, or both. The naturalization of the term “yellow fever” used in club promotion was especially problematic, since this term was profoundly based on western superiority and male domination. The term also brought me question the way non-white individuals use the racialized language in a predominantly white space. UBC is located in a white settler society, a space that is “established by Europeans on non-European soil”, as Razack explains (pp. 1). When naturalizing the term “yellow fever”, the male executive intended to attract non-Asian audience with racial/cultural preference to his imagined community. Yet he was completely ignorant of how the meanings and practices of this term do harm to an Asian female like me. I imagined that, if I were in a space that welcomes “yellow fever”, my body would be realized mostly in terms of my race and my gender, and I would be expected to perform as a stereotypical Asian female who is submissive, reserved, and feminine. In no way I would feel safe!

Gendered and Sexualized texts and images.

Using Razack’s concepts of social space, when seeking a place with my identity as a Chinese person in Imagine Day, I observed how different Chinese cultural clubs perform their values and visions: first, symbolic performance, such as the banners with Chinese language; second, interpersonal performance, such as the public speech from executives. Notably, it was difficult for me to find a safe space among the Chinese cultural clubs that promoted parties as their main activities, because the way they performed their social spaces put me under the risk of being gendered, sexualized and racialized.

Reference:

Razack, S. (2002). Race, space, and the law. Toronto: Between the Lines.

Tom: What is Theory? How to Teach it? (Notes by Leanne)

-Rima said theory is talking without examples =P

A theory is a set of difficult questions or problems posed in concepts. It is a set of concepts that asks us questions.

Concepts can come from everyday life – concepts about gender, sexuality, etc.

Example

The theoretical part

For example, let’s take a look at Marx and Engel’s German Ideology. “Ideology” from the German Ideology. “Ideology” is a buzz word like “social construct.” It is the idea that notions shapes. The question asked in the German Ideology is, do material conditions shape consciousness? What makes Germany so advanced in one way but not another.

Tying it in with examples from real life

What are the issues for this class?

Ex. The ideology of masculinity

-what it is to be a dude in university?

-think about that ideal – what are the material conditions that give rise to that

consciousness?

-the frat idea – they’re trying to gain status and a sense of belonging by joining a

Fraternity, it’s gives them the dude code

-why are they going to university – to train people to be useful to a capitalist society

Linking it to our class

We did field work by going to orientation/campus events. For example, we went to see how that masculinity and femininity are represented in that moral code.

CONNECTING IDEOLOGY TO WHAT’S GOING ON IN OUR CLASS (RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HOW THAT CONNECTS TO OUR EVERYDAY LIFE) – how does this take place in different places

In Summary

(1) Look for metaphors

-there re always metaphors, examples, analogy in theories – helps to crack the code of what theory is

-Ex. Marx and Engels – camera obscura – a distorted upside down reality when it’s filtered

through the camera obscura – gives us an idea of what ideology is Take that back to the guy

code – camera obscura cuts out a lot of the reality. (Tom uses a lot of diagrams)

(2) Look for the concepts

-you can find it and it is defined in the text

(3) Look for examples, research questions from the text then find your own examples, connect it to experience – look for metaphors!

When Teaching a Reading (Theory):

(1) provide context:

-who is the author

-what is the title of the writing?

-what was it written/published

(2) pull out a concept

-define it (ex. How would you define “compulsory heterosexuality”

(3) what are the implications? (applying the theory)

-the question: is the choice something that one can really make? (agency)

Ex. For the reading, you could Google Adrienne Rich and you’ll find out that she was a poet writing in the 2nd wave of feminism and Valverde was writing during the 3rd wave of feminism.

-this helps us to understand what the author is saying and their perspectives!

Bonus: check out Dive in the Wreck – good poem!