“On the first day of classes, campus is transformed and over 8000 new-to-UBC students and over 1000 faculty, student, and staff volunteers come together to welcome you to your new academic community and celebrate the start of the school year.” (Imagine UBC)

“The first-years are so unlucky, they get this cold and heavy rain on Imagine Day. Too bad for people at the booths. Who wants to be outside?” (talking with my friends)

Rain, rain, rain. As a featured outdoor event for new students (mostly first-year) to discover the student clubs and communities on campus, the Main Event seemed to have difficulties escaping the cold and heavy rain on the Main Mall on September 2, 2014.

Seeking a Space: Where is the Community I belong?

As a transfer student, that was my second school year at UBC, and naturally my second time being in the UBC Imagine Day. The Imagine Day description made I imagin that by connecting with the little space of a booth, I can later connect with a certain space on campus where I can call a community. This space could be a physical one (such as a club office or an event site) or/and an imagined one (such as a Facebook group, a friendship network), and it must be one where I feel comfortable revealing my identities (for example, a Chinese person) and behaving as myself. Yet my searching last year as one of the “new-to-UBC students“, I recall, did not lead to any fruitful outcomes. I signed up for the Meditation Community’s email list, but I had schedule conflict with all of their events; I paid $10 for the membership of CSSA (Chinese Students and Scholars Association) but found it useless; several clubs that I signed up didn’t even send me any newsletters. Besides, what UBC described as an “academic community” was largely absent in the Main Event, since nearly all the booths were presented by cultural, spiritual, and recreational clubs. Arts academic clubs, for instance, were told to present in the morning at Buchanan Courtyard, a space that was separated from where a wider audience located in the Main Event.

Wandering around the Main Mall among crowds of twenty-something-looking people, walking in and out among tents and booths, reading banners, signs and posters for information, writing down my name and email, talking or refusing to talk with others: I saw myself as one unit of complex identities attempting to build connections with other unites of identities. Using Sherene Razack’s concept of linking bodies with space in Race, Space, and the Law (2002):

“[T]he symbolic and the material work through each other to constitute a space” (pp. 8).

a space is not just an “innocent” space outlined by objects and people, it should be further analyzed as a social product (pp. 7). In other words, a space can be social, and its social meanings should be performed. In the searching of other spaces, bodies have to move, symbols and languages have to be shown, interpersonal interactions have to be performed (physically, verbally, emotionally). Occupying a bodily space in the Main Event, I saw myself entering, exiting, and re-entering different social spaces that were performed by groups of individuals with certain identities.

Performing a Space: A Chinese Community of What?

Redoing my searching this year, I tried to focus on one aspect that I was always interested in: the Chinese cultural clubs. Directly related to my identity as a Chinese student at UBC, I would like to use my perspective to briefly examine how a space is performed with social meanings. How do these clubs represent themselves? What kinds of space do they create at UBC?

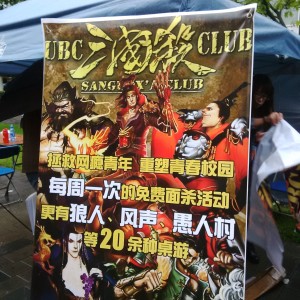

1. A Space of Language

A space can perform its social identities through verbal and written languages. It was easy for me to identify most of the Chinese cultural clubs by looking for signs and banners, since many of these material spaces were presented through Chinese characters. Interestingly, since modern Chinese have two written forms, some of the signs were in traditional Chinese, which was officially used in Hong Kong and Taiwan; some were in the simplified one, which was officially used in mainland China. This language difference not only showed the culture that the clubs intended to present, but also showed what audience these clubs were presenting to. Occasionally, I also hear Mandarin and Cantonese communicated between students. Building instant identity connections, language performs symbolic meanings through the material spaces; it also reflected the diverse cultural identities within the “Chineseness” of the clubs.

[Language representation (top&middle: in traditional Chinese; bottom: in simplified Chinese).]

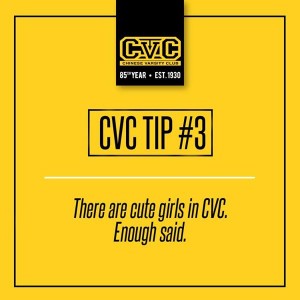

2. A Space of Racialization or/and Sexualization

Through asking questions to every Chinese cultural clubs I found, I noticed that the three most common events these clubs organize were parties, games, and ski trips. I imagined myself being in a club, a party room, and a Whistler hotel room, but I couldn’t imagine a conversation or a community. Once again, I found no way to seek an “academic community” among different Chinese cultural clubs. Moreover, I was shocked to hear some public announcements from two Chinese cultural clubs:

A male executive from one club spoke loudly to his surroundings: “….If you have yellow fever or Asian fever, this is the place for you.”

A male executive from another club said to the people who were passing by: “come for parties…… and get laid.”

Performing as representatives of their clubs, these two male executives presented their imagined community that I perceived as dangerous spaces. As a female I felt very uncomfortable with what these two particular clubs created within the public space of the Main Mall: the terms “yellow fever” and “get laid”, and the images (as show below) created a social spaces that was either racialized or sexualized, or both. The naturalization of the term “yellow fever” used in club promotion was especially problematic, since this term was profoundly based on western superiority and male domination. The term also brought me question the way non-white individuals use the racialized language in a predominantly white space. UBC is located in a white settler society, a space that is “established by Europeans on non-European soil”, as Razack explains (pp. 1). When naturalizing the term “yellow fever”, the male executive intended to attract non-Asian audience with racial/cultural preference to his imagined community. Yet he was completely ignorant of how the meanings and practices of this term do harm to an Asian female like me. I imagined that, if I were in a space that welcomes “yellow fever”, my body would be realized mostly in terms of my race and my gender, and I would be expected to perform as a stereotypical Asian female who is submissive, reserved, and feminine. In no way I would feel safe!

Gendered and Sexualized texts and images.

Using Razack’s concepts of social space, when seeking a place with my identity as a Chinese person in Imagine Day, I observed how different Chinese cultural clubs perform their values and visions: first, symbolic performance, such as the banners with Chinese language; second, interpersonal performance, such as the public speech from executives. Notably, it was difficult for me to find a safe space among the Chinese cultural clubs that promoted parties as their main activities, because the way they performed their social spaces put me under the risk of being gendered, sexualized and racialized.

Reference:

Razack, S. (2002). Race, space, and the law. Toronto: Between the Lines.