Dear UBC (past, future, and present) Students,

UBC is an incredible place- a “place of promise” as we see in some of UBC’s messages marketed to us. It provides us with an astounding number of opportunities to redefine, develop, and discover ourselves and turn students into productive, fully functioning members of society. I personally am very thankful to have had the opportunity to attain a rich and fulfilling education here at UBC and would not change my decision to attend UBC for my undergraduate degree. I’m not sure if I would have matured to the extent that I have at a different university than UBC. However, the purpose of this post is not to criticize or praise UBC as an institution of education, rather, I want to point out the importance of recognizing UBC as an institution not unlike many others that participate in our free-market system. Specifically, as with other major institutions, UBC profits off of (y)our identification with and participation in its reproduction, and this means that your reverence for the UBC brand is something this institution works very hard to maintain and survives from in ways far beyond what you might expect. In other words, your consumption of the UBC brand is a highly powerful act.

To explain using some theoretical approaches: let’s start with a Marxian concept. While people with little social science background might associate Marx with communism, he didn’t only talk about a utopian ideal, he was also really good at explaining how systems of power operate economically, but especially socially and politically. Specifically, Marx approaches power through the perspective of the social construct, meaning that power is simply a result of peoples’ thinking. As long as people attach certain values and meanings to symbols, power and control can not only be predicted, it can also be interrupted and changed.

A great quote that Marx uses to illustrate this is through his explanation of ideology in his famous piece called German Ideology: “Men are the producers of their conceptions, ideas, etc… Consciousness can never be anything else than conscious existence, and the existence of men is their actual life-process. If in all ideology men and their circumstances appear upside-down as in a camera obscura, this phenomenon arises just as much from their historical life-process as the inversion of objects on the retina does from their physical life-process.”

There is a lot to understand in this quote. Let’s break it down.

First, men are the producers of their conceptions, ideas, etc… this is essentially what I was explaining earlier, that people (you can ignore the gendered language Marx was using, which was normal during his time) ultimately attach meanings to what they see in the world, which are usually informed by value systems other people, like your family and your friends, taught to them as “normal” and expected.

Second, ideology is a word that Marx uses to explain why different classes of people exist. Marx saw the world as consisting of two classes, proletariats (working class) and bourgeoisie (business owners or managers). For Marx, the working class people were exploited by the business owners and he understood this as the result of a collective problem whereby power of business owners was a product of a collective survival of working class people based on wages through work. He saw this as a gross imbalance of power and wanted to understand why this imbalance persisted to the extent that it did during his time.

Third, a camera obscura is one of the first devices developed for the recording of images, right around Marx’s time. It works by completely blocking all light from a room, with the exception of a very small hole. After enough time passes, you can sit in the room and after your eyes adjust, an image of the world becomes refracted onto the wall opposite the hole and this image is an exact upside-down replica of what you would see if you were to put your eye to the hole from inside the room and look out onto the world. This is in fact how cameras work today, and it is how you see the world, literally with your eyes. Since your eye works with a refracted image onto your retina, the image becomes re-oriented to the correct version by your brain, which is connected to your eye through various nerves. You can learn more about the camera obscura through this cool Youtube video.

But I digress. Marx is saying that as images appear upside down and distorted on your retina and in a camera obscura, ideology also distorts peoples’ images of the world. This is because of peoples’ historical life-processes, which basically means the way groups of people have historically come to organize themselves and economically sustain themselves.

So you’re probably asking yourself, how does all of this tie in to UBC?

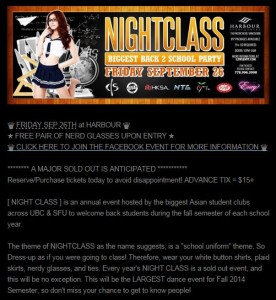

UBC is an education institution, which means that it requires a relatively large number of students to want to go there for their education each year. Universities need to address a large number of needs today in order to stay competitive. Some of these include employment opportunities for students after graduation, development of research and critical thinking skills, and student clubs and societies so that students get bored on campus. All of these will ultimately involve a great deal of time and organization on the part of someone, whether it be students, staff, or faculty and whether this work is paid or unpaid.

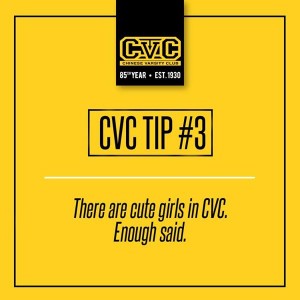

The “I am UBC” slogan is a great way to involve students in the institution’s branding. It attaches the university to the student’s identity, and it is a very clever way to get students to attach themselves and identify with the university. In doing so, it sets the tone and market demand for the university for years to come. It also means that a great deal of labour that the university depends on, such as student organizations, orienting new students to the university’s policies and procedures, and navigation of the university bureaucracy, can all become sought after forms of participation for students since they identify with the university in a way that is meaningful to them.

With the advent of social media, I am UBC has become #IamUBC. Try searching it on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram. You’ll see breathtaking images of ocean and mountains as a backdrop to the Rose Garden area, or you’ll see fresh fruit and vegetables being grown at the UBC Farm. You may also see tudor style architecture, shiny and interesting museum exhibits, or First Nations symbols showcased on these feeds. All of these are representations of the UBC brand that the university- and the people who attach such meanings to it (such as students like yourself) have reproduced over the recent weeks, months, and years.

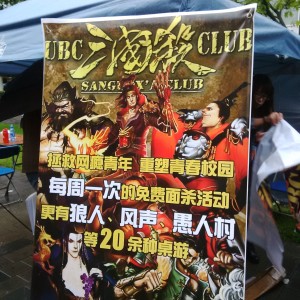

It is time to critically engage with #IamUBC at events like Imagine Day. This year, Imagine Day was overshadowed by a feisty rainstorm that ended up drenching festivities by the afternoon. I remember tabling for a student organization, Sociology Students’ Association. I enjoy what I do and I love interacting with students, new and established, in learning about their interests and putting on events engaging with social issues. It was participating in Imagine Day this year in this unique role that really made me think about my own role as a kind of representative of a certain part of the university to incoming Arts students this year. We had to “compete” with other clubs for students’ attention and curiosity. We ended up renting a button machine (which was the highlight of our table) in order to capitalize on students’ attention just to remain relevant in the sea of tables and booths. All of this is a part of the process of reproducing the I am UBC brand.

I remember seeing a friend of mine working at one of the tables and she seemed rather unhappy. After we chatted for a bit, she told me that she was actually an executive of one of the other student associations, but since she is doing an internship for one of the organizations on campus, she had to stay at that group’s booth instead of the one she identified with more. This is a demonstration of Marx’s concept of camera obscura, because it shows that peoples’ conception of things, like UBC or Imagine Day, is a product of their participation in and therefore attachment to certain ideas and values that make up institutions and organizations. In the case of UBC, it is the idea of personal development, achievement, and redefinition that all students are looking for as they go through a life stage or life transition into adulthood. The university profits from this arrangement of student identification, likely because students see a kind of freedom, or potential freedom, of this kind of identification. To see beyond the fuzzy images associated with #IamUBC and consider the ways you participate in UBC campus activities and organizations contributes to the university’s success means an ability to critically engage with who pays or profits from institutions like UBC.