My identities are complex. They keep changing and shifting focuses depending on context. And They should always be intersectional.

“my feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit.” – Flavia Dzodan

Reading this quote on Facebook today made me think of my positionality in relation to the #Ferguson issue. The jury officially announce that the white male police, Darren Wilson, face no charge shooting 18-year-old black citizen Michael Brown to death on August 9th in Ferguson, Missouri, United States. Started from Ferguson, a city with a large black community, solidarity events and protests spread over the U.S. and some parts of the world, many tagged as #BlackLivesMatter. Learning from Alice Goffman’s lecture earlier this semester that in low-income black communities, young men have to face policing, arresting, and killing in their everyday life in the U.S., I do not just see the shooting and the jury decision as a single issue but a systematic problem that put the African-American ethnic groups in fundamental disadvantage and injustice.

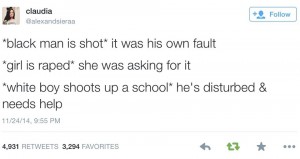

Why does this disturb me and why it is relevant to me? Because in this context I quickly see myself as a person of colour in a white-settler society (Razak, 2002) that is established upon white privilege. At the same time, along the line of Razak’s intesectional approach to space, gender, and race, I am aware that my position as an ally with the #BlackLivesMatter protest is not simply related to my skin colour, but a self that intersects with multi-dimensional identities such as in ethnicity, gender, and social location. To expand my thoughts I think it is good to start with this tweet:

[first, let me try to type in my thoughts in Chinese]

這幾行字簡約卻充滿爆炸性,因為其啓發我將種族和性別不公聯繫在一起。這在我看來,也是交織性女權主義的魅力。

[Then, I translate them into English]

These few lines are simple but explosive, since they push me to further see ethnic and gender oppression together (in a white-dominated patriarchal system). To me, this is the charm of intersectional feminism.

[as I learn sociology through an English-speaking education, I soon run out of words in Chinese and return my reflection to the English thinking mode]

To be sure, paralleling the experience of the “black man” and “girl” in contrast to the experience of the “white boy” does not mean that we should draw an equation mark between the two. My experience being a Chinese woman is very different from that of a black man. But the experiences of the blamed and the redeemed connect me to the movement of black people’s rights.

When I was taking SOCI 101 sociological theories in another university, I was confused about the feminist theory because I saw it as a combination of all kinds of social justice arguments. To be honest, I was not impressed at all and I came to resist the “feminism” label. I had negative feeling towards feminism as feminists make claims over almost every issue on injustice. To simply put, I was tired of seeing the label “feminism” everywhere. At the same time, “feminism” was a term that I often associated with the images of radical men-haters and naked FEMEN.

But now, when I am reflecting on how I have been reflecting on feminism during these few months, I see the value of feminism that intersects every social components together. Which means, nothing should be explained merely by race, gender, or class, etc. — it should be explained with these all together.

I first heard of the term “intersectionality” from the courses offered by the UBC Gender, Race, Sexuality, Justice program. I got to talk about it further through learning about it in some public lectures, and interacting with my friends who self-identified as feminists (mostly male!). This semester is very special to me in terms of the process of feminist self-realization. I never publicly claimed to be a feminist until I take SOCI433, which provides me with an intersectional approach to see my identities and other’s identities. The classroom goes beyond the physical space into the virtual space (Facebook group) of public discourses, and allows me discuss feminist topics and issues such as Emma Watson’s UN speech and rape cultural on UBC campus with friends and classmates. More importantly, throughout reading feminist writings by Azaia, bell hooks, and Beckie, I realize that feminism is a way of thinking of the world intersectionally, and acknowledging our own limited but international perspectives. For example, early in Azaia’s thesis, she acknowledges that her writing comes from a perspective of a white urban working-class female (2014, p. 20). In bell hooks writing, she also make it clear of her positionality as a black female.

After all, in this post I touched lots of bits and pieces of my identities. You may think there is no “theme” or a major theory. But this is exactly my point. In this post I try to briefly show you how my identities are intersected:

- my gender intersects with my ethnicity, which make me an ally of the #BlackLivesMatter;

- Chinese as my first language (everyday, reflective) intersect with English as my second language (academic, critical, reasoning)

- my past perception of feminism intersects with my current experiences of feminism.

- my social position as a UBC sociology student intersects with my gender, class, race, and other identities, which provide me with resource and access to critical-thinking education and further identity discovery.

My identities are complex. They could not, and should not, be reduced into a single one.

Reference:

Razack, S. (2002). Race, space, and the law. Toronto: Between the Lines.

Windwraith, A. (2014). Deconstructing the Language of Rape.

hooks, b. (2000). Feminism Is for Everybody: Passionate Politics.