I gave my first two-stage exam a few weeks ago. It wasn’t an approach I had considered until very recently. I had previously heard of exams with a group portion, but at that time the benefits weren’t clear to me, and frankly, it sounded odd so I didn’t give it much thought. A few months ago, I was reintroduced to the idea by Judy Chan at a UBC Course Design Intensive workshop. After hearing the process described in detail, the value was immediately clear. This concept aligns with my interest in facilitating effective learning strategies for students, in this case, retrieval practice.

The exam I just gave was a radical departure from anything I’ve done before. During the group portion, I could see through the students’ animated discussions that they were more engaged with the material than ever before. Two-stage exams will be my main approach from this point forward.

What is a two-stage exam?

There are many variations of two-stage exams. I followed a standard approach (Wieman, Rieger, & Heiner 2014) for my 50-minute exam:

- Create a normal exam, but cut the number of questions by 30%-40%

- First 30 minutes: students take the exam individually and hand it in when complete

- Next 5 minutes: students assemble in groups of four, and each group receives one new copy of exam (identical to individual exam)

- Last 15 minutes: in their group, students freely discuss and complete the exam (and hand in one copy per group)

- Students’ exam scores are weighted 85%-individual & 15%-group (or 100% individual if a student’s individual score is higher than their group score)

This seems complicated. Why is it such a great idea?

When students leave an exam, they engage in immediate hallway discussion about the correct answers to the most difficult questions. I remember as a student getting a question like that wrong, finding out the correct answer from a friend immediately after the exam, and retaining that information longer than most of what I’d learned in the class. The two-stage exam capitalizes on this energy. Students are given a small extrinsic motivation (potential increase in score), but most also have high intrinsic motivation to figure out the correct answers. The animated discussions my students had during the group portion of the exam is by far the most engaged I have seen them all semester. This is a great way for students to receive immediate feedback and give highly motivated peer instruction.

There is strong evidence that retrieval practice is one of the most effective learning strategies. The key to retrieval practice is that students attempt to retrieve knowledge from memory (without looking it up in their notes or text) even if they don’t know the answer. An exam certainly accomplishes this. For retrieval practice to work best, the student should quickly be given the correct answer. While students aren’t guaranteed to get the correct answer in their group, the improvement in scores in the group portion showed that students who got a question wrong individually were often able to arrive at the correct answer as a group. Based on our knowledge of retrieval practice, this should lead to improved retention of the material.

Brett Gilley and Bridgette Clarkston at UBC actually tested this (Gilley & Clarkston, 2014). I won’t go too deep into their clever design, but in a nutshell, they carried out a two stage exam where students were first tested on all material (topics A and B) individually. For the second portion, half of the students were tested individually on topic A and in a group on topic B, or individually on topic B and in a group on topic A. The individual re-testing is not normally part of a two-stage exam, but it controlled for the extra time spent engaged with the topic in the group portion. Two days after the exam, students had a surprise quiz covering topics A and B. In this quiz, students performed significantly better on the material they had covered in the group portion vs. material that they had just considered individually. This is evidence that the group portion of the exam helped students better learn and retain the material covered on the exam.

Challenges

I was unsure how to best assign groups. I polled the students, and ~75% preferred selecting their own groups. They were evenly split on whether to use the same (self-selected) groups they use for labs. I allowed them to choose their own groups and encouraged them to decide as a lab group if they wanted to test in that group or another. This went smoothly, and I didn’t hear any complaints.

The biggest challenge was logistical. I teach a 50-minute class with 168 students. I didn’t want to eat up exam time unnecessarily. My TAs and I got into the lecture hall immediately after the previous class ended and laid out the two versions (same questions, different order) of the exam where we wanted students to sit. In the meantime, students remained outside the lecture hall and assembled in their groups. We then ushered students to their seats by group. Even though they were spaced every-other seat, they sat near their group members. This took longer than I hoped, so the exam started a few minutes late. The transition to the group portion was smooth. On conclusion of the individual exam, we collected those and gave a new exam to each group. Students re-arranged themselves a bit so they could sit directly with their group, but since they were already seated in the same row, this was fast. The transition from individual to group exam took about 3 minutes.

I didn’t explicitly consider my grading time when deciding to do a two-stage exam. I initially assumed it would be longer, but it was actually shorter. For example, 100 students taking a (normal length) 20-question exam equals 2,000 questions to grade. In the two stage exam, it would be shortened to 12 questions. So there would be 100 individual exams and 25 group exams to grade, or 125 * 12 = 1,500 questions.

The biggest downside was that by shortening the exam, each question was worth more, so the students’ scores were more (statistically) noisy. I need to more carefully craft my exams, because a bad question or two can make a big difference on a short exam. In particular I need to better balance the exam points across the topics/lectures covered.

Student performance

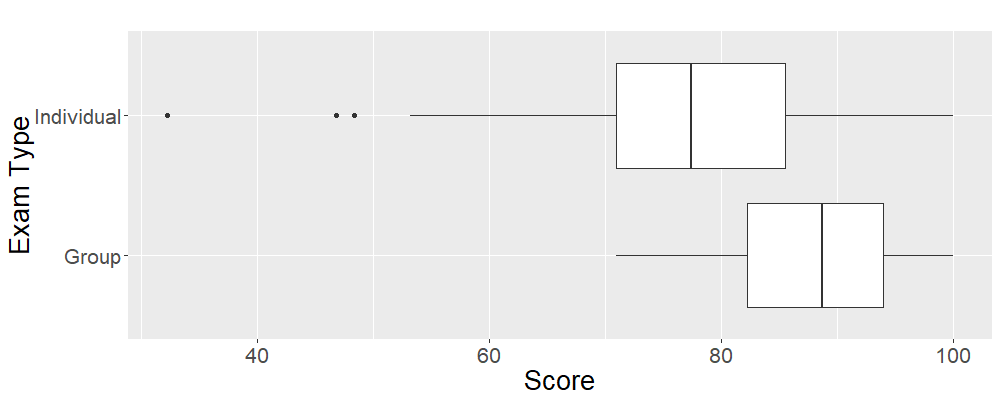

Unlike Gilley and Clarkston, I was just giving an exam (and not conducting an experiment), so I can’t directly test student gains in understanding of the material. Nonetheless, I can compare individual and group scores. Unsurprisingly, nearly all students (157/168) scored higher on the group portion than the individual portion (mean = 87.6 vs. 77.3). (For fairness, students scoring higher on their individual exam than group were given their individual score for both portions of the grade.)

Interestingly, score gains varied widely. A student with a high individual score doesn’t have much room for improvement, while a low-scoring student does. Also, the group member with the lowest individual score is likely to benefit greatly from the group’s collective knowledge, while the highest-scoring member is not. To examine this, I grouped students into quartiles based on their individual score. Students in the bottom quartile averaged a 20% gain in the group portion, while students in the top quartile gained an average of only 2%.

| Individual Score Quartile | Mean Individual Score (%) | Mean Group Score (%) | Mean Score Gain (%) |

| 4 | 90.8 | 92.7 | 1.9 |

| 3 | 82.1 | 89.1 | 7.0 |

| 2 | 75.1 | 85.9 | 10.8 |

| 1 | 63.4 | 83.2 | 19.8 |

Student Feedback

Students generally report positive views on two-stage exams (Rieger & Heiner, 2014; Wieman, Rieger, & Heiner, 2014). In my course, students were mostly positive about the experience. In the class period after the exam (prior to release of grades), I asked a few clicker questions.

- Did the group portion enhance your learning?

- Yes – 66%

- No – 33%

- Do you think the 2-stage exam was worthwhile (vs. a traditional exam)?

- Yes – 54%

- No – 26%

- No strong opinion – 19%

So, 2/3 of the students thought they received a learning benefit, and twice as many students thought the approach was worthwhile than those who didn’t. I asked these questions without much thought, as I was just interested in a quick impression of students’ opinions. Now that I’ve thought more about these numbers, I am quite curious how students’ views are related to the score bump they receive. I hypothesize that students who performed well individually and gained little in the group portion may be more ambivalent about the approach while students who had a large score increase would view the approach more favorably. On the other hand, students who scored poorly on the individual portion may feel uncomfortable in the group if they don’t feel able to contribute. Or, a high-scoring student might see value in explaining the correct answers to their classmates even without a score bump. These are questions I plan to investigate further.

Conclusions

I am a fan of the two-stage exam. It is a bit more challenging to implement than a traditional exam, but the benefits outweigh that challenge. Those challenges also relax for a longer (e.g., 90-minute) exam period. For my next midterm, I will focus on speeding up the seating and exam distribution, and making sure my exam is well-crafted and evenly balanced across the material covered.